From court musician to freelance artist

As the son of a court musician and grandson of the former court bandmaster Beethoven soon became a court musician

for the Elector of Cologne. A wunderkind career like Mozart his father intended for him could not be realised.

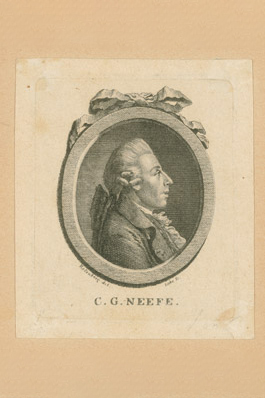

Already as a 12 year old did Beethoven deputise for court organist Christian Gottlob Neefe. When the court band

was reorganised at the change of government between Elector Maximilian Friedrich and Maximilian Franz, the

14-year old boy was permanently employed as second court organist. His pay amounted to 150 florins; his father

received 300 florins. In 1787, Beethoven was sent to Vienna for studies but had to return after only two weeks

when his mother fell seriously ill.

Christian Gottlob Neefe (1748-1798)

Organ "Beethoven's organ"

From court musician to freelance artist

The first years in Vienna

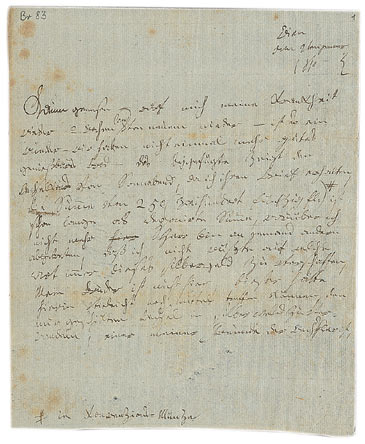

In 1792, Beethoven went again to Vienna for studies. This time he should never return to Bonn. Before his

departure, one of his most important patrons, Count von Waldstein, signed Beethoven's album with the famous

words "You shall receive Mozart's spirit from Haydn's hands". Beethoven was granted leave of absence by the

Elector and received a scholarship of 100 thalers.

Ludwig van Beethoven, 1802

In Vienna Beethoven quickly socialised with the art-loving aristocratic society of the music metropole. His

travel diary bears a few entries of his expenses during the beginning of his time in Vienna: The monthly rent

for his room was 14 florins, meal and wine cost 16 florins. The 150 florins Beethoven received from the Bonn

Elector were thus not enough to live on, let alone pay the rent. Various activities such as teaching and playing

the piano at noble salons soon made him known as an artist and ensured the support of the nobility in later

years.

Prince Karl von Lichnowsky (1756-1814)

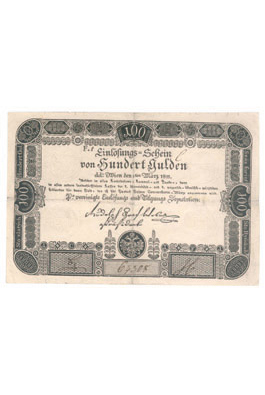

Paper money (Stadt-Banco-Zettel) from 1806

In 1800, Prince Karl von Lichnowsky provided Beethoven with an annual salary of 600 florins that was to be paid

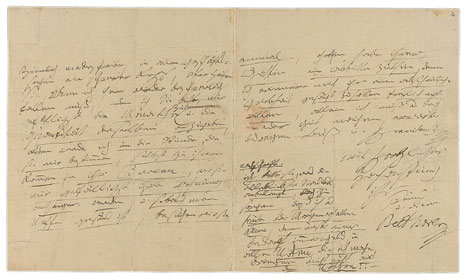

until Beethoven had a regular income. In a letter to his Bonn friend Franz Gerhard Wegeler, Beethoven was quite

optimistic, if not euphoric, about his current living conditions and wrote about the yearly payment Lichnowsky

granted him until he would find a suitable position, that his compositions paid well and that between six and

seven publishers were always interested in his works so that he was the one who demanded and they would pay. He

mentioned his strongly economical life and that he aimed at having one day for an Academy concert each year. On

April 2, 1800, Beethoven had held the first concert for his own benefit at the renowned Hofburg theatre.

Although he set great store on his independence even back then, he strove for a well-paying position. After his

employment as opera composer and bandmaster at the Theatre an der Wien between 1803 and 04 he directly applied

at the Royal Court Theatre at the end of 1807. However, he asked for the exorbitant sum of 2,400 florins (even

bandmaster Salieri only earned 1,200 florins) as well as the earnings from the third performance of the opera he

was to compose each year. In exchange for another free work, he also wanted to use the existing premises once a

year to hold a concert for his own benefit. Beethoven's application was rejected.

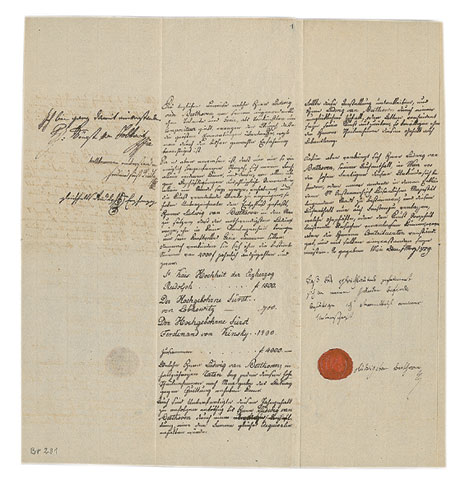

Beethoven's work-scholarship granted by Prince Lobkowitz, Prince Kinsky and Archduke

Rudolph

Conclusion of the "annuity agreement"

In the autumn of 1808 Napoleon's brother King Jerome Bonaparte of Westphalia offered Beethoven the position of

bandmaster at the Kassel Court for a generous annual salary of 600 ducats. Beethoven spread this news in Vienna

and quickly added that he was willing to accept. Ignaz von Gleichenstein and Countess Erdödy then made an effort

to keep Beethoven in Vienna. The composer was asked to name his conditions and Gleichenstein included these in a

draft agreement. Apart from 4,000 florins a year, Beethoven also demanded the right to undertake art journeys,

the title of Imperial Bandmaster and an annual concert for his own benefit at the Theatre an der Wien.

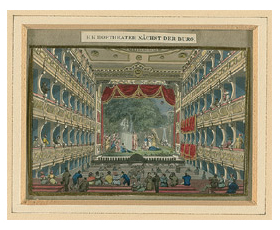

The efforts were rewarded and three patrons were found to raise the sum demanded. The draft agreement was

reduced to the essential and signed by Princes Kinsky and Lobkowitz as well as Archduke Rudolph a few days

before the indicated date as a so-called "Annuity contract". The three signatories obliged to pay Beethoven an

annual amount of 4,000 florins in bank notes (Banco-Zettel) his life long unless the composer found a permanent

employment. It was their belief that only a man free of worries was able to compose such great and outstanding

works and thus the signers decided to enable Ludwig van Beethoven to fulfil his most relevant necessities and to

not inhibit his powerful genius. In exchange, Beethoven promised to stay in Vienna or Austria at least.

Stadt-Banco-Zettel from 1800

Beethoven's work-scholarship granted by Prince Lobkowitz, Prince Kinsky and Archduke

Rudolph

Thanking the patrons

Out of gratitude, Beethoven dedicated various works to his patrons. Archduke Rudolph, the youngest son of

Emperor Leopold II and brother of Emperor Franz, was one of Beethoven's piano and composition students and

became the composer's most important patron. He was an excellent pianist and now and then engaged in composition

activities himself. Beethoven dedicated him far more pieces than anybody else. The piano sonata op. 81a (Les

Adieux) intended for him illustrates the Archduke's departure, absence and return to Vienna during the war in

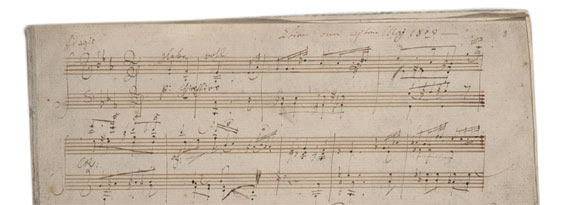

1809 in three movements. On the title page of the manuscript Beethoven wrote: "The Farewell, Vienna, May 4,

1809, on the departure of his Imperial Highness the revered Archduke Rudolph". Thus, the sonata can be seen as a

piece of composed biography.

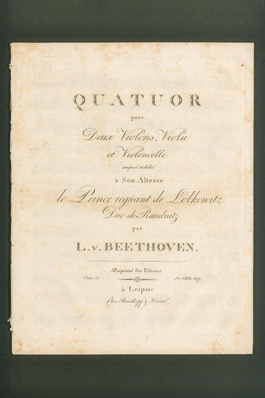

Prince Lobkowitz was dedicated Beethoven's new string quartet op. 74 as well as the fifth and sixth symphony

(also dedicated to Count Rasumowsky). Beethoven wrote the piece in the summer and autumn of 1809 while staying

in Baden close to Vienna.

Archduke Rudolph of Austria (1788-1831)

String quartet in E flat major, op. 74

While Beethoven believed that his scholarship provided him with a safe foundation to fully focus on his art and

be free from all material worries, reality should soon teach him a lesson. The Napoleonic Wars devoured large

sums of money. Just like during the Seven-Year War a decision was made to increase the amount of Banco-Zettel.

The total circulation of bills rose from 74 million in 1797 to 1,061 million in 1811. The gap between the

Banco-Zettel and the silver coins once intended for their coverage had already broadened so much that the notes

could not longer be exchanged into metal money. Consequently, the Banco-Zettel continued to lose its buying

power and led to a general price rise and impoverishment of large population classes.

Upon signing the agreement in the spring of 1809, Beethoven's annual salary of 4,000 florins in Banco-Zettel was

equal to 1,620 florins in convention money (silver currency) - the salary of 600 ducats for the position at the

Kassel court would have equalled 2,700 florins convention money. By August 1810, it only equalled 890 florins,

in December, at the lowest exchange rate, only 416 florins.

Piano sonata in E flat major, op. 81a

Finally, the Austrian government realised that a national bankruptcy was inevitable and followed the advice of

Court Chamber President Count Wallis. In 1811 all Banco-Zettel was devaluated. According to the decree of

Emperor Franz I from February 20, 1811, soon called "Bankrottpatent", all circulating Banco-Zettel was to be

devaluated to a fifth of its face value from March 15 on and changed into "redemption coupons" for the new

"Vienna currency" (W.W.) until January 31st, 1812.

In order to reduce the loss of agreements under private law such as annuities, pensions etc. until the decree

came into force the new value of these payments was calculated using the Banco-Zettel exchange rate valid when

the agreement was signed. For this purpose, a table was developed. The value for March 1809 was 248, so the

amount determined at the closing of the contract equalled the sum to be paid multiplied by 2.48.

Beethoven's work-scholarship granted by Prince Lobkowitz, Prince Kinsky and Archduke

Rudolph

Payout problems I

Beethoven now tried to convince his patrons to ignore the table and pay him the respective sum not in

Banco-Zettel but redemption coupons. Although according to Beethoven's assurance initially all three patrons

gave their consent, only Archduke Rudolph granted Beethoven the full amount.

Redemption coupon from 1811

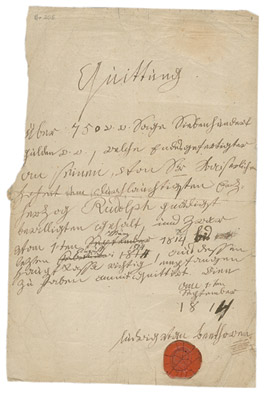

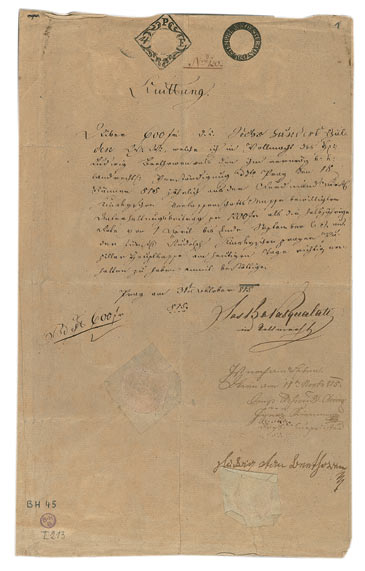

Receipt for Archduke Rudolph's main cash office

Due to the aggravated economic conditions Prince Lobkowitz had become highly indebted. His payments to Beethoven

stopped in September 1811. On June 1st, his assets were put under "amicable administration", half a year later

under state administration. The Prince lost the right to dispose over his property and belongings, had to

dissolve his band and leave Vienna.

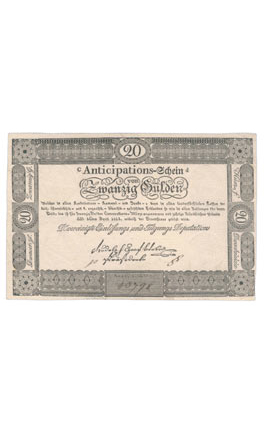

Anticipation coupon from 1813

Files for the trial against Prince Lobkowitz

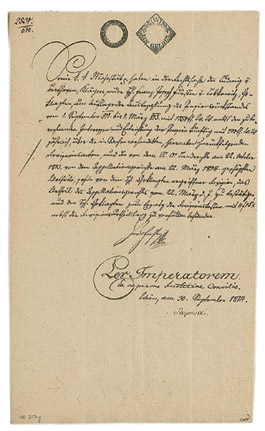

In light of an imminent bankruptcy Beethoven filed a complaint against Prince Lobkowitz at the Lower Austria

County Court that was allowed at first instance. On October 22nd, 1813, Lobkowitz was sentenced to pay the due

as well as the future pensions in full face value of the Vienna currency. The opposing party then filed an

appeal at the Appellate Court of Lower Austria and on March 22, 1814, Prince Lobkowitz was given the opportunity

to rebut Beethoven's proof - a verbal promise of the Prince - by taking an oath. As part of his appeal Lobkowitz

contacted the Emperor who, however, confirmed the decision of the Appellate Court. Because Lobkowitz refused to

take an oath at court, the original verdict came into force on April 19th, 1815, and Beethoven received the due

sum in three instalments until the end of August of the same year.

Beethoven's work-scholarship granted by Prince Lobkowitz, Prince Kinsky and Archduke

Rudolph

Payout problems II

Not only for the payments from Lobkowitz did the composer have to ask the court for help but also for the

payments from Prince Kinsky. Although Kinsky had ordered his cash office in January 1812 - and therefore before

Beethoven asked him to ignore the table - to pay out Beethoven's salary using the table, the payments were

delayed for quite a while. On November 2nd, 1812, Kinsky died after an equestrian accident. Beethoven now asked

Princess Karoline Kinsky for a payment of the due sums in redemption coupons. The princess, unfortunately, was

not able to make a decision without the consent of the guardianship authority. Eventually, Kinsky's share was

determined 1,200 florins Vienna currency from the Prince's death day onwards by the court.

The receipt refers to the first payment after the court's decision. The scholarship was to be paid in two

instalments of 600 florins each. On a form, Beethoven had to issue a receipt that - apart from seal and his

signature - also had to consist of a certificate that the recipient of the payments was a living person (issued

by a rectory serving as a registry office).

Receipt for Prince Kinsky's main cash office

Kinsky's payments were often delayed. In order to accelerate the process, Beethoven authorised his lawyer

Nepomuk Kanka who had represented him during the trial.

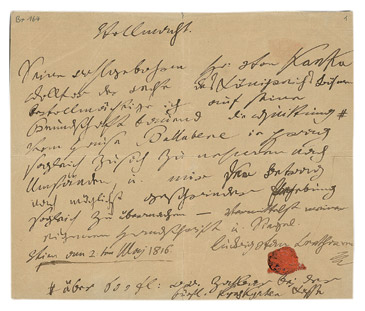

At first the Prague bank Ballabene was to implement the payout but Beethoven informed Kanka in a letter that

Pasqualati had just told him after one month and six days that Ballabene was too influential for this matter and

that he would now have to draw on his lawyer to obtain his receivables.

Authorisation for Kanka in Prague

On May 1st, 1816, Beethoven also wrote Kanka about his intention to dedicate a composition to Princess Kinsky

and ask for the payments he was entitled to in a letter. Such a letter does not exist and therefore might never

have been written. After the tedious negotiations regarding his salary, the composer should have known that any

new try would also fail. Thus, he gave the composition the self-explanatory title "To hope".

Cost of living in Vienna at Beethoven's time

Composition and demand

Living conditions in Vienna at Beethoven's time were far different from today and thus cannot be compared

directly. To get an objective picture, Beethoven needs to be seen within his time. The then cost of living

mainly comprised expenses for food, rent and clothing. In his "New Sketch of Vienna" from 1804 contemporary

Johann Pezzl concluded that the minimal expenses for a man living by himself, without any splendour or posh

public office and only socialising with the middle classes amounted up to 967 florins. However, if one includes

theatre visits now and then and other public or private amusement, less than 1,200 florins a year are not

sufficient. To be able to compare this information with today, such "amusement expenses" will have to be

included. But even then 41 % were still spent on food (without taking any spare time activities into account

this was 52 %) while modern society spends only a fifth on food. Clothing, with 19 %, was significantly more

expensive than today (6 %), too. Unlike then we now spend more money on rent and additional costs (37 % today

versus 14 % back then). If calculating the budget for 1809 and taking into consideration the price development

for food and rent, a total of 1,600 florins results. The financial support Beethoven initially obtained from his

patrons was thus more than twice the budget a middle class man disposed of. In the most extreme years of 1816

and 1817, the composer's salary of 3,400 florins was even below Pezzl's budget of about 3,750 florins

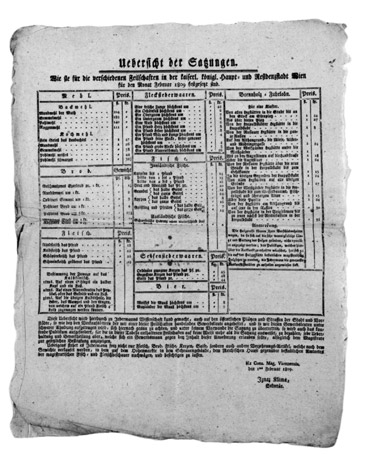

Overview of statutes, February 1809

Pezzl´s list shows why food prices were so significant. While contemporary documents of Beethoven´s early Vienna

years already indicate a noticeable price increase for food, the situation worsened during the occupation of

Vienna by French troops in May 1809 and finally led to bottlenecks in supply. In the second half of the year

food prices rose by 50 %. Prices for flour, bread, meat, fish, candles, soap, beer and firewood were fixed by

the government. When even these were raised, life became more and more difficult. In February a pound of beef

cost 18, in September already 27 kreuzers. All other prices were adapted to the market situation and hardly

affordable for the broad population.

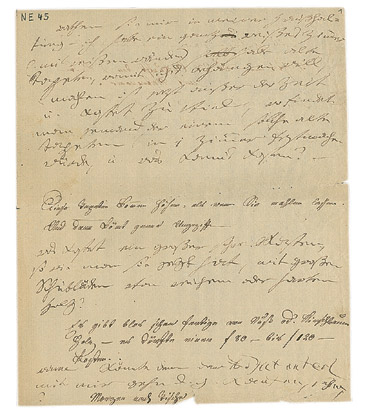

Beethoven reports the same. To explain why he insisted on receiving his remuneration for a composition in

Convention coins, he wrote publisher Breitkopf & Härtel from Leipzig that a pair of boots now cost 30

florins, a

coat between 60 and 70 florins and that due to the French occupation his annual salary of 4,000 florins had lost

its value and was barely worth 1,100 florins in Convention coins. In 1792 Beethoven noted 6 florins for a pair

of boots, in 1810 they cost 30 florins - a five-fold price increase.

Written dialogue with Haslinger

3 kreuzer, Vienna currency, back

Even though the increase of food prices was far quicker and more irregular than of rents, these were also

subject to inflation and price rise. In 1816, Beethoven paid a rent to Count Lamberti that was ten times higher

(1,100 florins in Vienna currency equal 5,500 florins in Banco-Zettel) than the rent he paid six years earlier

at the Pasqualati house (500 florins, Banco-Zettel).

The extensive correspondence with Nannette Streicher, owner and the driving force of a leading Vienna piano

manufactury shows that Beethoven often sought advice in household matters.

Music publisher Tobias Haslinger, a friend of Beethoven, helped him move from his summer residence to his town

residence in October 1817. It might be possible that Beethoven asked for advice on wallpaper and chest of

drawers on this occasion.

Cost of living in Vienna at Beethoven's time

Food expenses

After two preceding bad harvests, the extreme inflation and price rise reached a second height in 1817. Many

food prices had doubled or even tripled. In addition, the Vienna Congress had engulfed enormous amounts. So it

is not surprising that Beethoven told Johann Peter Salomon in June 1815 he was afraid of losing his salary

again. At that time, 100 florins Convention coins equalled 400 florins and 50 kreuzers Vienna currency. Only

around 1820 the rate stabilised at 100:250.

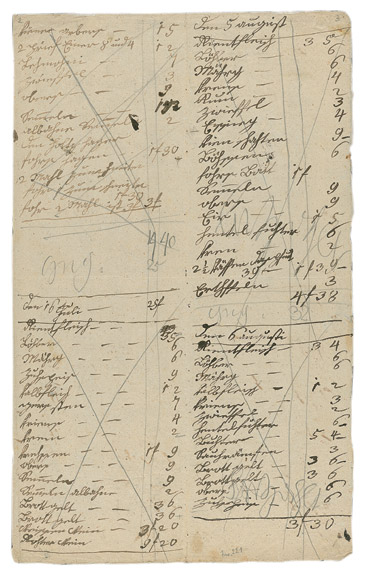

Two sheets from a household book

Because of the financial distress and his distrust that increased with his deafness, Beethoven forced his

housekeepers to record their expenses in household books. All purchased items as well as their price had to be

written down. Beethoven reviewed the entries, noted down how much money he had given his housekeeper and how

much she had returned and finally crossed out the entire page to show it had been reviewed.

Cost of living in Vienna at Beethoven's time

Piano prices

Expenses for the nephew

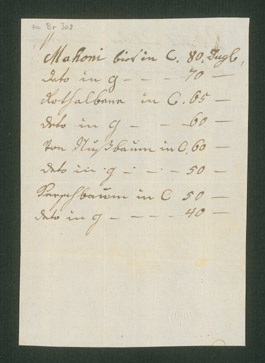

The price list shown here indicates the prices for pianos by Anton Moser who was not among the first but belonged

to the solid and most affordable piano manufacturers in Vienna. The different prices ranging between 40 and 80

ducats depended on the inlay used and sound range of the instrument. Cherry wood was the cheapest, mahogany the

most expensive material. The sound range was either five octaves plus second or five and a half octaves. Other

renowned piano makers charged 100 ducats for grand pianos with mahogany inlay and bronze fittings, Nannette

Streicher sold her plain pianos for at least 66 ducats. In the mid-1820s, her plain pianos made from nut wood in

the form of a grand piano and with a sound range of six octaves cost around 80 ducats whereas mahogany pianos

with lavish fittings and six and a half octaves started at 165 ducats. Other piano manufacturers offered rather

plain virginals for only 33 ducats.

Once in a while Beethoven acted as an "instrument agent and advisor". It seems that he himself never had to buy

one. As a famous piano player and composer, he was able to revert to loans and presents of renowned piano makers

who thus achieved their intended advertising effect.

After his brother Karl Kaspar died in November 1815, Beethoven obtained custody for

his nephew Karl. On May 10, 1817, Beethoven and his sister-in-law Johanna settled their dispute regarding Karl´s

inheritance. They agreed that Johanna would contribute half of her widow´s pension to the education of her son

who would receive another 2,000 florins Vienna currency a year from his father's inheritance. Johanna kept the

house 121 in the Alservorstadt suburb. Because the relationship between the composer and his sister-in-law was

quite taut, Beethoven always tried to exclude Johanna from custody for her son. A tedious legal dispute followed

that lasted until 1820.

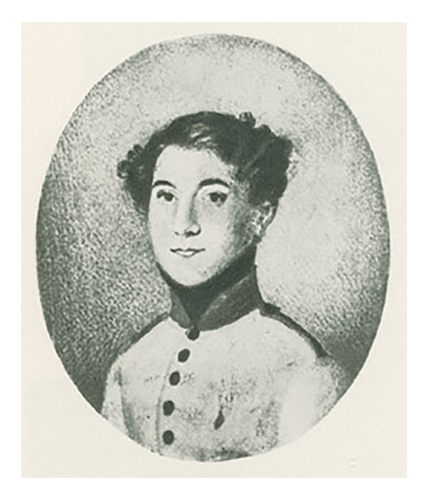

Nephew Karl van Beethoven (1806-1858)

Contract with Johanna van Beethoven

At first, Karl attended a number of different schools, among them the institute of Cajetan Giannattasio del Rio.

School fees amounted to 275 florins Vienna currency per quarter. In a letter to Ferdinand Ries who wanted to

arrange a charity concert for him, Beethoven wrote on May 8th, 1816, that his salary of 3,400 florins in

Banco-Zettel was hardly enough to cover for his expenses such as a rent of 1,100 florins, 900 florins for the

housekeeper and up to 1,100 florins for school fees and that he planned to put up his little nephew as the

school was not good. He also complained about how much one would have to earn to be able to make ends meet.

Later, Karl lived with Beethoven and attended the University of Vienna before he switched to the Vienna

Polytechnical Institute in 1825. Eventually, Karl opted for a military career.

Beethoven and his publishers

His sales strategies

The remunerations Beethoven received from his publishers were by far his most important source of income. His

increasing deafness deprived him of another significant income source, such as performances as a musician. Thus,

he became a skillful negotiator. As a composer, Beethoven wanted to remain free and independent and create

timeless compositions for a worldwide audience. Ordered works were the exception, however, he offered noble

patrons an exclusive right to use important pieces for a period of six to twelve months in exchange for payment

before these compositions went to press. Thereafter the piece was offered to several competing publishers. Fixed

one-time remunerations were set that also included the right to adapt the piece for smaller instrumentations.

Apart from this, Beethoven received no additional payment. Reprinted or copies of unprinted or printed works

distributed by professional scribe offices did not bring him any earnings.

The publishers certainly gained quite some money with composers who received far smaller payments for their

works but still had a broad target group in mind. To publish a Beethoven composition, however, also made the

publisher's reputation rise. In addition, Beethoven's music enjoyed a certain constancy thus allowing large

numbers of later new editions. And so it proved worthwhile even though the composer's remuneration often

exceeded half of the total cost for a printed edition.

Letter to Breitkopf & Härtel dated January 2nd, 1810

In 1809 Beethoven sold a collection of works to his preferred Leipzig music publishing house Breitkopf &

Härtel,

comprising the oratorio "Christ on the Mount of Olives", op. 85, the opera "Leonore", op. 72 and the Mass in C

major, op. 86, for a total fee of 250 florins Conventional currency. As opposed to the agreement, the

remuneration was paid in Banco-Zettel that lost its value from day to day. Therefore, Beethoven demanded the

Banco-Zettel to be taken back and the full amount be paid out in silver currency. A few months later, Beethoven

asked for 250 ducats for another grand collection of compositions (op. 74 to 86). When the publisher tried to

talk him down to 200 ducats, Beethoven reacted with these words: "It is not my intention, as you believe, to

become a profiteer in art, one who only composes to augment his riches, heaven forbid, but I enjoy an

independent life and cannot be without a small fortune and so the composer's remuneration must honour the artist

and all he undertakes. I shall not mention it to anyone that Breitkopf & Härtl gave me 200 ducats for these

compositions, you as a music publisher more humane and educated as all other publishers should have the

intention not to pay the artist a scanty remuneration but enable him to fully administrate the duties expected

of him -".

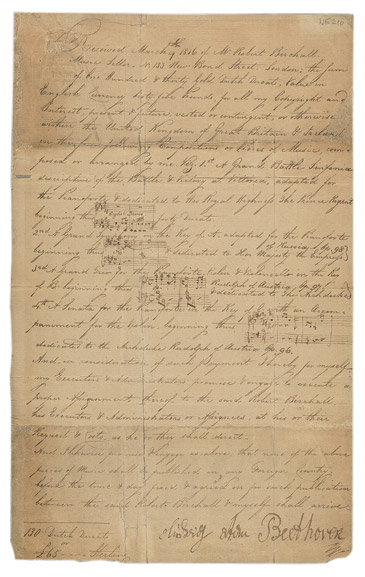

Certificate of ownership and receipt for Birchall

Beethoven offered his compositions to several publishers for various European markets under the condition that

the editions would have to be published at the same time to avoid losses for individual publishers. The markets

were distinctly separated between Austria and politically fragmented Germany (including Leipzig, Bonn, Berlin

and Mainz) as well as France and Britain. For a fee of 130 Dutch ducats he conceded the rights of property and

publication in Britain and Ireland for the piano sections of the battle symphony "Wellington's Victory or the

Battle of Vittoria", op. 91, the Seventh Symphony, op. 92, the piano trio op. 97 and the violin sonata op. 96 to

the London publisher Robert Birchall. Publisher Steiner from Vienna thus had to delay his edition of the battle

symphony's piano part slightly - one of the few compositions highly targeted to public acceptance.

Beethoven and his publishers

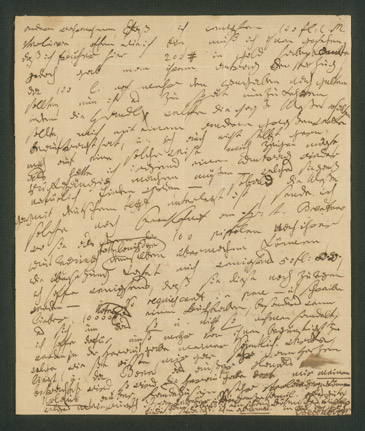

The "Missa Solemnis" case

It was the Missa Solemnis, his greatest spiritual music composition and his best work in his own eyes, for which

Beethoven undertook the most complicated and dubious sales efforts ever.

Letter to Simrock dated November 28th, 1820

Already in February, one month before the enthronement of his pupil Archduke Rudolph as Archduke of Olmütz - the

occasion the mass was composed for - but eventually three years before its completion, Beethoven and his former

Bonn friend Nikolaus von Simrock agreed on a fee of 100 Louis d'or coins. Despite Simrock's announcement to

equal the value of the Louis d'or coin with the Friedrichs d'or coin (pistole) (worth only 7.5 florins

Convention coins), Beethoven felt taken in as he calculated with 9 florins. He had received an advance payment

for the fee of 900 florins Convention coins from his friend Franz Brentano who he was able to repay in two

instalments after three years. Beethoven then opened negotiations with publishers Peters in Leipzig and Artaria

in Vienna and several others. In the end, the mass was sold in 1824 for 1,000 florins Convention coins to the

Schott publishing house in Mainz together with the Ninth Symphony that alone brought 600 florins.

"Missa Solemnis", op. 123

Before it went to press, Beethoven offered copies of the Missa Solemnis made by his own scribes to 28 European

courts for a fee of 50 ducats each. He received ten orders that brought him an additional gain of 1,650 florins

Convention coins.

Beethoven as concert organiser

As it was customary for that time, Beethoven also organised concerts. Concerts for the benefit of a musician or

composer, the so-called "Academies" always came with a high financial risk. Usually, the composer whose latest

works were played or the virtuoso who wished to demonstrate his ability to the audience, served as the organiser

himself which led to an additional workload often regarded as cumbersome and particularly tedious. The

organiser's duties included the creation of the programme, selection of musicians, announcing the event as well

as arranging advance bookings. Apart from that a suitable place had to be found - usually a theatre or

multi-purpose hall such as the Redouten Hall - and rented. The first public hall used only for concerts was

built no earlier than 1831 by the Society of the Friends of Music, founded in 1812.

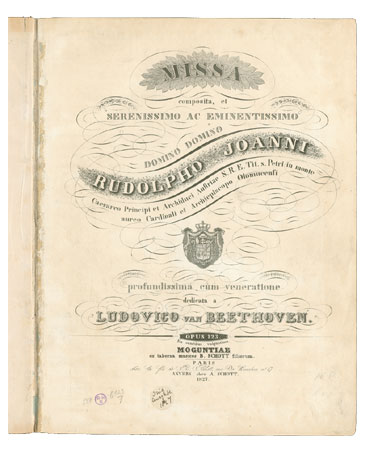

Beethoven managed to organise the National Court Theatre next to the castle for his first own Academy on April

2nd, 1800. The fact that he had dedicated his piano sonatas op. 14 to Josephine von Braun, wife of the director

of both court theatres, one year earlier certainly helped him. The programme featured a symphony by Mozart, two

pieces from Haydn's Creation, a piano concert by Beethoven (probably number 1, op. 15), his Septet op. 20 and

the First Symphony op. 21 as well as a free piano fantasy. Such long, mixed programmes where the instrumental

compositions were interrupted through short vocal pieces were quite usual. Financially seen, the concert was

probably successful although Beethoven did not follow the conventions and only charged an entrance fee "as

usual".

The upbeat mood he spread in a conversation with his boyhood friend Franz Gerhard Wegeler regarding his future

in Vienna in June 1801 and his hope to hold an Academy at the theatre each year, speaks for a successful

concert. However, the remaining 26 years in Vienna would see only eight concerts for Beethoven's benefit of

which only four proved financially successful. But these Academy concerts always represented an occasion for

quite generous contributions made by the nobility

Vienna Hofburg Theatre around

Placard for the Academy concert on April 2nd, 1800

The best known examples are the concerts that Beethoven held during the Vienna Congress. Between September 1814

and June 1815 the leading European regents convened in Vienna. Their entourage included diplomats and

aristocrats. An extensive programme with balls, opera performances and concerts was organised. After the success

of "Wellingtons' Victory or the Battle of Vittoria", op. 91, that hit the patriotic nerve of that time,

Beethoven seized the opportunity once more and swiftly composed the grandiose cantata "The Glorious Moment", op.

136, following only commercial aspects. On November 1814, "Wellington's Victory" and the Seventh Symphony were

performed once more together with the new cantata in front of an enthusiastic audience and the heads of

government. The concert was repeated for Beethoven's benefit on December 2nd and to the benefit of the St Marx

hospital on December 25th. The expenses for the first two events amounted to 5,108 florins Vienna currency. The

fact that Beethoven made more money through his concerts in 1814 then in all other years together is certainly

due to the generous support of the Russian Tsarina. The Vienna magazine "Friedensblätter" from December 24th,

1814 wrote she gave Beethoven a generous donation of 200 ducats.

"Wellington's Victory or the Battle of Vittoria", op. 91

"The Glorious Moment", op. 136

Dedications and ordered compositions

The polonaise op. 89, composed especially for the Tsarina, might have been a token of gratitude for her noble

contribution to his Academies during the Vienna Congress. However, the composer also received 50 ducats as a

gift for the dedication. She additionally paid him 100 ducats for the violin sonatas op. 30 published in 1803

and dedicated to her husband Alexander I. These are the only dedications that resulted in a payment for

Beethoven even though the composer dedicated some more pieces with probably the same intention to others.

Polonaise for piano in C major, op. 89

Elisabeta Alexejewna, Tsarina of Russia (1779-182

When dedicating the battle symphony "Wellington's Victory" op. 91 to the Prince Regent of Britain, the later

King George IV, Beethoven certainly hoped for a generous remuneration. Unfortunately, his hopes were in vain,

despite numerous later tries to remind the king of this omission. The dedication of the Ninth Symphony op. 125

to Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm III did not fulfil Beethoven's intention either. While he had hoped for a

medal, he simply received a ring of minor value and a plain thank-you note. Despite such disappointments,

Beethoven profited from dedications as they enhanced the value of a composition in the public's eyes. Of course,

he dedicated many pieces to his patrons as a token for gratitude. In general, dedicating a composition was not

only a positive deed for the composer and enabled him to demonstrate his admiration in public but also for the

recipients who felt adorned through "their" piece. The dedications to the composer's noble patrons outnumber

those to his friends by far.

Violin sonata in C minor op. 30 No. 2

The few ordered works were composed for noble customers (string quartets opp. 127, 132 and 130 for Prince

Galitzin, Mass op. 86 for Prince Nikolaus II. Esterházy), music societies (Ninth Symphony for the London Royal

Philharmonic Society), theatres (such as the play music opp. 113 and 117 for the theatre in Pest) and publishers

(for example the adaptation of folk songs for the Scottish publisher George Thomson). With regard to the fee

Beethoven charged, the order of the Society of the Friends of Music in Vienna to write an oratorio for Carl

Bernard's text "Der Sieg des Kreuzes" (the victory of the cross) is most noteworthy. Despite an advance payment

of 400 florins Vienna currency and a fixed remuneration of 300 ducats, Beethoven just outlined a short sketch.

He did not like the playbook. This example is quite illustrative that it was art, not money that reigned in his

world.

Beethoven's financial circumstances

A publisher in lieu of a bank

Due to the difficult economic situation Beethoven was regularly confronted with financial shortcomings. When the

payments by his patrons virtually stopped for three years in 1811 and were resumed in 1815, the buying power had

changed drastically and could not be compared to that of 1809. Consequently, Beethoven's annuity, once fixed

with the intention of freeing him of all financial worries, temporarily did not fulfil its purpose. He

repeatedly had to ask publishers, friends such as the Brentanos and family like his brother Johann for loans.

When his brother Kaspar Karl fell ill with tuberculosis in 1813 Beethoven helped him with a loan. When the money

could not be paid back, he received the amount from his publisher Sigmund Anton Steiner and conceded him the

demand for payment. Beethoven pledged to provide Steiner with a new and unpublished piano sonata in case the

amounts would not be paid back when due and guaranteed him the exclusive right to buy several works. The

composer chose the piano sonata in E minor, op. 90 as a special means of paying his debts.

Piano sonata in E minor, op. 90

In the following years publisher Steiner repeatedly served as Beethoven's "private bank" and the composer took

up several loans and even successfully invested money. On July 16, 1816 he wrote Steiner to express his trust

and ask him to securely invest his small capital - a sum of 4,000 florins Convention coins with an interest rate

of 8 %. The money's origin is not clear but it may well have been the earnings from the two Academy concerts

held in 1814 and the generous contribution from the Tsarina.

On June 1st, 1816, the Privileged National Bank of Austria was founded as an independent incorporated company.

With the aim of a currency consolidation the Banco-Zettel of the Vienna currency was withdrawn and changed into

new bank notes of the original Convention coins at a rate of 2.5 to 1. Around 1820 the currency had stabilised.

Now Beethoven's work scholarship was 1,360 florins which equalled the annual salary of a bandmaster. A musician

at the court band made between 400 and 700 florins, comparable more or less to the salary of a teacher at a

higher institute (they supplemented their income through lessons and private performances). Medium-level public

servants were paid more than 1,000 florins and Beethoven's housekeeper received 129 florins, full board and

lodging included.

In his tax return dated January 15th, 1818, Beethoven indicated an income of only 1,500 florins Vienna currency

that equalled the annuity share Archduke Rudolph paid. All other earnings from the sale of his compositions as

well as the shares of Princes Kinsky and Lobkowitz were omitted. The class tax was a precursor to today's income

tax and was levied from 1800 onwards. From 1802 on tax payers had to classify themselves into tax classes

according to their income and provide an explanation. Beethoven shortened the official wording drastically.

Beethoven's tax declaration from 1818

Beethoven's financial circumstances

Notes and needs

After three years Beethoven asked Steiner for a return of his invested capital - Steiner did not subtract the

composer's debts - and bought eight bank shares of the Austrian National Bank on July 13th, 1819. When Beethoven

did not make the stipulated repayments, Steiner reminded him politely but with emphasis at the end of 1820.

Obviously, Beethoven had bitterly complained about the previously set interest rate of 6 %, which was even less

than the fixed interest rate for his capital investment.

"I cannot be content with your conclusion on my bill as I charged you 6 % interest on lent money while giving

you 8 % on the money you invested and paid these and your capital in a timely manner. What's sauce for the goose

is sauce for the gander. I am not able to offer loans without interest. I served you as a friend in need,

trusted your word, have neither been intrusive nor bothered you and must so reject the reproaches thrown at me.

- If you consider that my loan to you now nears its fifth year, you will see that I was nothing more than an

intrusive creditor. Even now, I would spare you and be more patient if I were not in need for money. - If I were

less convinced about your help and word, I would offer you more time despite the hardship on me. 17 months ago I

returned 4000 florins Convention coin or 10000 florins Vienna currency as capital and did not subtract my

outstanding money it now seems double the pain to be in need for money after trusting your word and despite my

good will. Each knows best where the shoe pinches and so I conjure you not to let me down and find means to pay

my bill as quickly as possible.-"

Letter from Steiner to Beethoven dated December 29th, 182

Beethoven noted down his thoughts on origin and composition of the debt that amounted to 2,420 florins Vienna

currency:

"1300 fl. were probably taken up in 1816 or 17; - 750 fl. Vienna currency even later, perhaps 1819; - 300 fl. I

took

up for Mrs. v. Beethoven a few years ago; - 70 fl. were probably paid for me in 1819 too."

The first item is the loan Beethoven received on May 4th, 1816, the second one the loan from October 30th, 1819.

The

amount of 70 fl. might be identical to 72 fl. Steiner paid to Bernard in August of 1816 on Beethoven's behalf.

The

last amount of 300 fl. was owed by Johanna van Beethoven in 1818. On January 8th, 1814, Beethoven told her in a

letter that he had amortised the debt.

Regarding debt amortisation, Beethoven wrote the following:

"Aside: For payment 1200 fl. can be authorised annually in two instalments. -"

All in all, Steiner had added an interest amount of 520 fl. Vienna currency (1,200 fl. Convention coins equal

300

fl. Vienna currency). In the end, Steiner had to wait until the summer of 1824 until he received the repayment

of

all loans.

Letter to Salzmann around February 8th, 1823

In 1823, Beethoven sent a letter to Franz Salzmann, then chief accountant at the Privileged Austrian National

Bank in Vienna. The composer owed 100 fl. to his tailor who had already threatened to file a complaint. Apart

from the fact that Beethoven wanted to pay at least a part of the money back Franz Brentano had lent him three

years ago as advance payment of the expected remuneration for the Missa Solemnis. Before lending on his shares

again, he wanted to receive the due dividend. Therefore, he informed Salzmann: "I am in need of your help again

as I can only write down some music. Excuse the inconvenience of asking you to name the months and quantity."

And postscript: "With regard to the wonderful dividend, I am asking you to arrange for it to be paid today or

tomorrow as one like me always is in need for money and all these musical notes don't pay my needs!!"

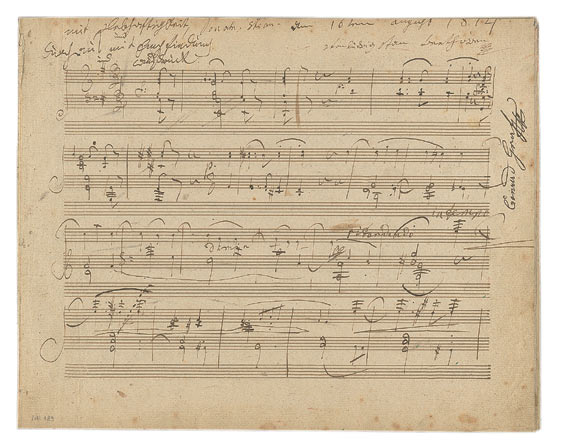

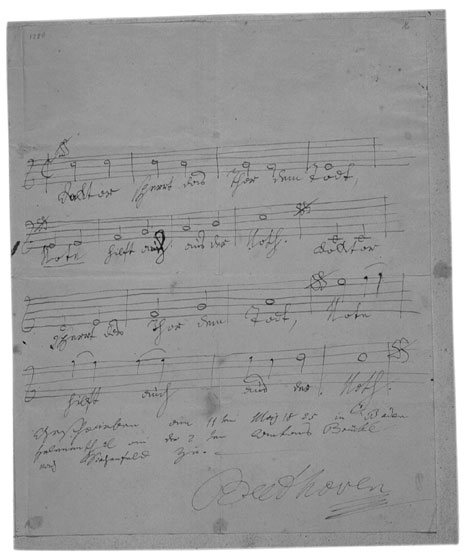

Canon "Doktor, sperrt das Tor dem Tod", WoO 189

The pun of the German words "Note" (musical note) and "Not" (distress, hardship) was often used by Beethoven,

for example in the canon he sent to his doctor Anton Braunhofer in May 1825 after his convalescence: "Doktor,

sperrt das Tor dem Tor - Note hilft auch aus der Not" (Doctor, shut out death - notes save from distress).

Braunhofer had asked Beethoven for "a few insignificant notes"; he mainly wanted something handwritten from

Beethoven. In this case, the German word "Not" (hardship, distress) obtains a double meaning: One the one hand

composing musical notes ("Note") helps Beethoven out of his financial distress ("Not"), on the other hand it

also eases his psychological distress caused by the prolonged sickness.

Beethoven's financial circumstances

His shares

Share of the Privileged Austrian National Bank issued to Ludwig van Beethoven

Beethoven repeatedly used his shares as security for loans, he lend on them and later amortised them.

Furthermore, he received an annual dividend of 30 fl. Convention coins, paid twice a year in January and July.

He

obtained an additional payout of the bank's gains in the form of an exceptional dividend after the annual

balance of

accounts in January. The capital gain was immense: Between 1819 and 1825, the price for one share more than

doubled

from 500 fl. to 1,202 fl. Because Beethoven always considered the share as inheritance for his nephew Karl and

thus

not intended for sale, he preferred contracting debts to reducing this fortune. Despite his intention, he had to

sell one share in September of 1821 as his financial situation had drastically worsened due to a prolonged

sickness.

In January 1827, Beethoven declared his nephew Karl the sole heir of his belongings and seven bank shares.

After

consulting with his legal counsel Bach and Stephan von Breuning - then Karl's custodian - he added the following

a

few days before his death: "My nephew Karl shall be the sole heir, the capital of my inheritance shall be given

to

his natural or testamentary heirs." As it was feared that Karl would support his highly indebted mother with

Beethoven's inheritance, he should only receive the earnings while the capital was intended for his own heirs.

Apart

from the two shares now owned by the Austrian National Bank, two other shares are at the Vienna City and State

Library. In 1864 and 1874, the Deposits Office handed both shares over to Karoline Johanna van Beethoven,

daughter

of Karl and Caroline Barbara (born Nasken) van Beethoven.

The shares of which only a few friends and his brother knew were the main part of Beethoven's inheritance (73

%).

The composer led a rather frugal life and spent only minor sums on luxury articles, died as a rich man. Just 5 %

of

the Vienna citizens left a similar or higher fortune, 77 % left only a tenth or less. Based on the conversion

factors calculated by Roman Sandgruber and under reserve, Beethoven's inheritance can be estimated at around

145,000

Euro. To compare: Bandmaster Antonio Salieri left three times as much, Joseph Haydn, bandmaster and "private

composer" for Prince Esterhazy twice as much.

Beethoven certainly did not lack anything and was not an impoverished artist. Still, his repeated complaints are

to

be taken seriously as they show that he always worried about his financial situation since he did not have a

permanent employment. Whatever the case may be, he was able to fulfil his wish of living an independent life,

especially in an art-related aspect.

Currency table

Money circulating in Austria at Beethoven's time

1. Money of the Austrian empire and Hereditary Lands

1753-1858 Convention coins (C.M.)

1 thaler = 2 florins (fl.C.M.) = 120 kreuzers

1 Penny = 3 kreuzers

Bohemia: 1 Gröschl = ¾ kreuzer

Vorlande: 10 kreuzers C.M. = 12 kreuzers (Hereditary Land)

Gold coins

1 Ducat = 4 fl.C.M. 30 kreuzers (official rate 1786-1858)

1762-1811 Vienna Banco-Zettel (B.Z.)

1796 1 fl.C.M. = 1 fl.B.Z.

1800 1 fl.C.M. = 1.15 fl.B.Z.

1805 1 fl.C.M. = 1.5 fl.B.Z.

1810 1 fl.C.M. = 4.92 fl.B.Z.

1811 1 fl.C.M. = up to 10.94 fl.B.Z.

After 1811 Vienna currency (W.W.)

1 florin W.W.= 5 fl.B.Z

30 kreuzers B.Z. divisional coins = 6 kreuzers W.W.

15 kreuzers B.Z. divisional coins = 3 kreuzers W.W

1811 1 fl.C.M. = 2.19 fl.W.W.

1813 1 fl.C.M. = 1.59 fl.W.W.

1815 1 fl.C.M. = 3.51 fl.W.W.

1816 1 fl.C.M. = 3.27 fl.W.W.

1819 1 fl.C.M. = 2.49 fl.W.W.

1816 Return to the Convention coins

1 fl.C.M. = 2.5 fl.W.W. = 12.5 fl.B.Z. (fixed rate from 1820 onwards)

3 kreuzers W.W. = 3/5 kreuzer C.M.

2. Value of foreign coins in Convention coins

Gold coins

1 Doppia (Milan) = 7 fl.C.M. 12 kr.

1 Ducat (Italy, Bavaria, Salzburg, Netherlands, etc.) = 4 fl.C.M. 18 kr. - 4 fl.C.M. 28 kr.

1 Louis d´or (France) = 7 fl.C.M. 20 kr. - 9 fl.C.M. 12 kr.

1 Max d´or (Bavaria) = 5 fl.C.M. 54 kr. - 6 fl.C.M. 45 kr.

1 Pistole = approx. 7 fl.C.M. 30 kr.

1 Souverain d´or = 13 fl.C.M. 20 kr.

Silver coins

1 Kronenthaler (Netherlands and other) = 2 fl.C.M. 12 kr.

1 Laubthaler (France) = 2 fl.C.M. 16 kr.

1 Pound (Britain) = 10-11 fl.C.M.

1 Reichsthaler (Prussia) = 1 fl.C.M. 30 kr.

1 Ruble (Russia) = 1 fl.C.M. 40 Kr.

1 Scudo (Milan) = 1 fl.C.M. 46 kr. - 2 fl.C.M.

Approximate conversion rate to Euro

1790 1 fl.C.M. = 23.982 Euro

1830 1 fl.C.M. = 15.458 Euro

fl.=florin; kr.=kreuzer

List of selected literature

"Alle Noten bringen mich nicht aus den Nöthen!!". Beethoven und das Geld, Begleitbuch zu einer Ausstellung des

Beethoven-Hauses, hrsg. von Nicole Kämpken und Michael Ladenburger, Bonn 2005.

Ludwig van Beethoven. Briefwechsel Gesamtausgabe, hrsg. im Auftrag des Beethoven-Hauses Bonn von Sieghard

Brandenburg, 7 Bände, München 1996.

Ludwig van Beethovens Konversationshefte, hrsg. im Auftrag der Deutschen Staatsbibliothek Berlin von Karl-Heinz

Köhler, Grita Herre u.a., 11 Bände, Leipzig 1972-2001.

Axel Beer, Musik zwischen Komponist, Verlag und Publikum. Die Rahmenbedingungen des Musikschaffens in

Deutschland im ersten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts, Tutzing 2000.

Beethoven und andere Wunderkinder, hrsg. von Ingrid Bodsch in Zusammenarbeit mit Otto Biba und Ingrid Fuchs,

Bonn 2003.

Otto Biba, Der Sozial-Status des Musikers, in: Joseph Haydn in seiner Zeit, Ausstellungskatalog, Eisenstadt

1982, S. 105-114.

Ernst Bruckmüller, Zur sozialen Situation des Künstlers, vornehmlich des Musikers, im Biedermeier, in: Künstler

und Gesellschaft im Biedermeier. Wissenschaftliche Tagung 6. bis 8. Oktober 2000, Ruprechtshofen, N.Ö., hrsg.

von Andrea Harrandt und Erich Wolfgang Partsch, Tutzing 2002, S. 11-30.

Hans-Jürgen Gerhard, Vom Leipziger Fuß zur Reichsgoldwährung. Der lange Weg zur "deutschen Währungsunion" von

1871/76, in: Währungsunionen. Beiträge zur Geschichte überregionaler Münz- und Geldpolitik, (= Numismatische

Studien 15) Hamburg 2002, S. 249-288.

Alice M. Hanson, Die zensurierte Muse. Musikleben im Wiener Biedermeier, Wien 1987.

Alice M. Hanson, Incomes and Outgoings in the Vienna of Beethoven and Schubert, in: Music & Letters, Oxford,

64

(1983), S. 173-182.

Andrea Harrandt, Freischaffende-Berufsmusiker-Staatsbeamte. Die Verdienstmöglichkeiten für Komponisten im

Biedermeier, in: Künstler und Gesellschaft im Biedermeier. Wissenschaftliche Tagung 6. bis 8. Oktober 2000,

Ruprechtshofen, N.Ö., hrsg. von Andrea Harrandt und Erich Wolfgang Partsch, Tutzing 2002, S. 107-120.

Ernst Herttrich, Beethovens Widmungsverhalten, in: Der "männliche" und der "weibliche" Beethoven. Bericht über

den Internationalen musikwissenschaftlichen Kongress vom 31. Oktober bis 4. November 2001 an der Universität der

Künste, hrsg. von Cornelia Bartsch, Bonn 2003, S. 221-236.

Eduard Holzmair, Der Staatsbankrott vom Jahre 1811 in der Erinnerung von Zeitgenossen, in: Mitteilungen der

Österreichischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft 17 (1971), S. 18-21.

Michael Ladenburger, Beethoven und die Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien: Mitteilungen zum Oratorium "Der

Sieg des Kreuzes" oder: Der Verdienst der Geduld, in: Studien zur Musikwissenschaft 49 (2002), S. 253-297.

Joseph Karl Mayr, Wien im Zeitalter Napoleons. Staatsfinanzen, Lebensverhältnisse, Beamte und Militär, Wien

1940.

Julia Virginia Moore, Beethoven and inflation: hol´ der Henker das Ökonomisch-musikalische!, in: Beethoven

forum, London, 1 (1992), S. 191-223.

Julia Virginia Moore, Beethoven and musical economics, Ann Arbor 1987.

Alfons Pausch, Ludwig van Beethoven. Steuererklärung aus dem Jahre 1818. Eigenhändige Fassion des Komponisten

mit Text des kaiserlichen Steuerpatents von 1806, Köln 1985.

Johann Pezzl, Neue Skizze von Wien, Erstes Heft, Wien 1805.

Johann Pezzl´s Beschreibung von Wien, 7. Ausgabe, Wien 1826.

Günther Probszt, Österreichische Münz- und Geldgeschichte, 3. Auflage, Wien, Köln, Weimar 1994.

Bernhard Prokisch, Die Münzschatzfunde Österreichs aus der Franzosenzeit, in: Mitteilungen des Instituts für

Numismatik 28 (2004), S. 16-24.

Roman Sandgruber, Die Anfänge der Konsumgesellschaft. Konsumgüterverbrauch, Lebensstandard und Alltagskultur in

Österreich im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert, München 1982.

Roman Sandgruber, Wirtschaftsentwicklung, Einkommensverteilung und Alltagsleben zur Zeit Haydns, in: Joseph

Haydn in seiner Zeit, Ausstellungskatalog, Eisenstadt 1982, S. 72-90.

Maynard Solomon, Beethovens Tagebuch 1812-1818, Bonn 2005.

Maynard Solomon, Economic Circumstances of the Beethoven Household in Bonn, in: Journal of the American

Musicological Society 50 (1997), S. 331ff.

Alexander Wheelock Thayer, Ludwig van Beethovens Leben, fortgeführt von Hermann Deiters und vollendet von Hugo

Riemann, Bd. 3, 2.Auflage, Leipzig 1911 und Bd. 5, Leipzig 1908.

Peter Urbanitsch, Zum Stellenwert des Mäzenatentums im frühen 19. Jahrhundert (unter besonderer Berücksichtigung

der Komponisten), in: Künstler und Gesellschaft im Biedermeier. Wissenschaftliche Tagung 6. bis 8. Oktober 2000,

Ruprechtshofen, N.Ö., hrsg. von Andrea Harrandt und Erich Wolfgang Partsch, Tutzing 2002, S. 31-57.

Vom Pfennig zum Euro. Geld aus Wien, Katalog zur Sonderausstellung des Historischen Museums der Stadt Wien, Wien

2002.

Legal notice

Publisher:

Beethoven-Haus Bonn

Bonngasse 24-26

D-53111 Bonn

Germany

Texts:

Dr. Nicole Kämpken

Dr. Michael Ladenburger

This temporary exhibition was shown from 13.05.2005 to 25.08.2005 in the Beethoven-Haus.

Austrian National Bank

Austrian National Bank