1800 - 1830

Beginning and precursors

Any architectural or plastic monument displayed in public to honour an outstanding person can serve as a

monument.

Therefore, the Beethoven bust which Franz Klein produced in 1812 can be seen as a monument itself because

Beethoven's friend, Andreas Streicher, ordered this bust and intended to display it in a hall of his piano

manufacture along with other portraits of admired musicians. The room served as a concert hall, so the public

had access to the bust. Although the sculpture is quite modest and its main function is just to portray the

composer, it can already be regarded as the first Beethoven monument.

Cast of Beethoven´s life mask from 1812

Ludwig van Beethoven bust by Franz Klein (1812)

The aspect of veneration becomes much more visible when taking a look at Beethoven's tomb which some friends of

the composer had put up on the Währing cemetery.

The tomb resembles a group of tombs erected at the end of the 18th and early 19th century for which monumental

architectural elements were used to honour the deceased in an elevated way and enhance their importance.

Obelisks were especially popular for these middle class tombs.

Ludwig van Beethoven's tomb on the Währing cemetery in Vienna (1828)

Soon, these memorials lost their original purpose and tombs became middle class monuments which could be put up

almost anywhere. An early example for such a genuine monument for a member of the middle classes is the obelisk

erected for Johann Georg Büsch, a grammar school teacher from Hamburg. The similarity of such monuments to

Beethoven's tomb gives evidence that people in Vienna followed these ideas and that Beethoven's tombstone marks

the border between evocative memorial and monument.

1830 - 1845

The first Beethoven monument

Briefly after the composer's death, the cities of Bonn and Vienna felt the desire to put up a monument for

Beethoven. As it was rather unusual to erect a monument in honour of an artist who had just died, the memorial

should be fairly modern.

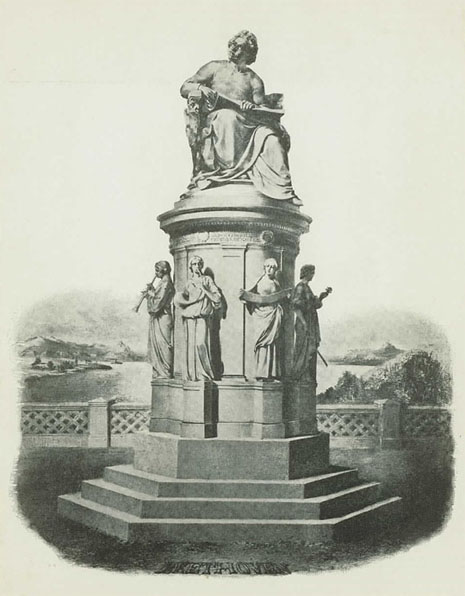

As a result, Vienna artist Friedrich von Amerling (1803-1887) and sculptor Ernst Julius Hähnel (1811-1891) from

Dresden chose to depict Beethoven in contemporary clothing in their drafts. To express the composer's creative

achievements, both artists portrayed Beethoven while composing and holding a writing feather in his right hand.

Draft for a Beethoven monument by Friedrich von Amerling (1840s)

While it would take another 40 years until a Beethoven monument was finally erected in Vienna, the city of Bonn

had a monument put up already in 1845.The ceremonial unveiling of the memorial was preceded by a long and

arduous process of creation characterised by many disputes among the members of the monument committee. The

involved musicians, historians and artists had fairly different opinions about how a monument for Beethoven

should look like.

Ernst Julius Hähnel: Beethoven-Denkmal auf dem Bonner Münsterplatz (1845)

After many tries, Julius Hähnel was finally able to convince the Bonn committee in favour of his concept which

included a Beethoven statue on a high pedestal adorned with allegorical reliefs. After Franz Liszt eased the

project's financial problems through a generous contribution, the monument could finally be completed. Its

unveiling was celebrated with a several day long music festival which founded the tradition of the still

existing Beethoven festivals in Bonn.

1845

The Beethoven monument on the Münsterplatz in Bonn

When a competition for designing a Beethoven monument was held in Bonn, a number of more or less renowned German

sculptors applied for this reputable project. In the end, the draft by Ernst Julius Hähnel, a successful

sculptor from Dresden and Munich, was chosen. His concept was regarded as modern and still elevated enough.

Beethoven monument in Bonn by Ernst Julius Hähnel (1845)

Hähnel portrayed Beethoven in the clothing typical for German and Austrian middle classes during the first half

of the 19th century: Shirt, neckerchief, long sleeved jacket and long trousers. However, the artist added a

large coat to give the composer a certain superior impression.

Beethoven's pose - his legs are slightly apart and he holds a writing feather in his raised right hand - should

express his musical inspiration as well as the trendsetting aspect of his art.

Reliefs from the pedestal of the Bonn Beethoven monument

Whereas Hähnel's Beethoven statue was met with criticism - people considered the statue as either too elevated or

too plain - the reliefs which Hähnel created for the high pedestal found the public's approval.

They feature allegorical depictions of the different types of music composed by Beethoven.

1845 - 1900

Further development of the Bonn type of monument

When designing the Beethoven monument for Bonn, Ernst Julius Hähnel used a monument type that was quite popular

for the honouring of middle class artists, scholars and scientists in the 19th century. The depicted person

usually stood with their legs slightly apart on a more or less square pedestal which was decorated with

inscriptions and reliefs. In most cases they wore contemporary clothing as well as a large coat to enlarge them

optically and render them more monumental.

Other examples for this type of monument include the monument for Jean Paul in Bayreuth (1841), the Goethe

monument in Frankfurt (1844) and the Herder monument in Weimar (1850).

Ernst Julius Hähnel´s Beethoven monument on the Münsterplatz in Bonn (1845)

Theodore Baur´s Beethoven statue at the Library of Congress Washington D.C. (second

half of the 19th century)

This way of depiction was popular all over Europe and continued well through the first half of the 20th century.

German-American sculptor Theodore Bauer (1835-approx. 1902) reverted to it when creating the Beethoven statue

for the Library of Congress in Washington D.C.

1845 - 1910

The time of the great Beethoven monuments

The tradition of plain monuments showing a standing Beethoven on a more or less high pedestal continued well

through the second half of the 19th century. At the same time, quite a different and much more monumental style

developed where the composer usually sat in an armchair or on a throne.

Friedrich Drake´s draft for a Beethoven monument (around 1840-45)

As one of the first artists, sculptor Friedrich Drake from Berlin (1805-1882) designed such a monument. Drake

probably began developing his ideas shortly after Beethoven's death in the 1830s. When the competition for the

Bonn Beethoven monument was held, he submitted a draft which is characterised particularly by a lavishly

decorated pedestal and the fact that Beethoven is shown in a sitting position.

Although Drake's draft was regarded as too heroic and therefore not chosen by the monument committee, his basic

concepts should lay the path for the further development of the Beethoven monuments of the late 19th

century.

1850 - 1910

Beethoven becomes an "Olympian figure"

In portraits and monuments, outstanding musical achievements of a person were traditionally expressed by adding a

lyre. This instrument, originally reserved for god Apoll and muses Erato and Terpsichore, can already be found

in 18th century depictions of musicians and composers.

On the one hand, this motive should refer to the musical context. On the other hand, a concrete relation to the

Olympian gods and muses should be established. Simultaneously, artists aimed at expressing music's divine source

of inspiration.

Beethoven as Apollo by Gustav Blaeser (around 1840)

Apollo with kithara (first century BC)

On a painting by Willibrord Joseph Mähler (1778-1860) the 34 year old Ludwig van Beethoven already holds a lyre

in his hand. In the monuments that were to be put up for Beethoven, the composer was soon equated with Apoll. In

drafts from 1845, the composer is portrayed in the large coat so typical for ancient gods and holding a lyre and

sometimes even Apoll's laurel wreath. The model shown here, created by Gustav Blaeser (1813-1874) for the Bonn

Beethoven monument, is a typical example for this idea.

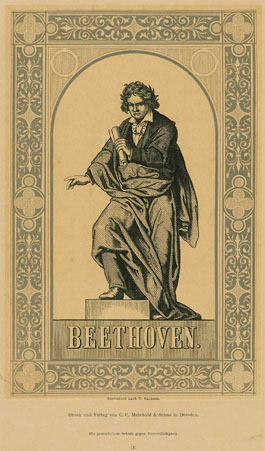

Draft for a Beethoven monument by Emil Eugen Sachse, woodcut from around 1890

Whereas this type of Beethoven depiction was met with criticism and deemed too heroic in the first half of the

19th century, the general taste later changed drastically. Now the theoretical link between Beethoven and the

god became more and more popular until a complete heroisation of Beethoven was reached at the end of the 19th

century.

Emil Eugen Sachse's (1828-1887) work clearly expresses the transition from the middle class Beethoven monument

from around 1850 and the heroic interpretation that came up in the second half of the century. Beethoven is

still portrayed in a standing position and wears the clothes typical for 1825. However, his coat is far more

voluminous than in older drafts and resembles the robes worn by the ancient gods. The laurel wreath in his hands

is another sign of this relation.

1878 - 1880

Caspar Zumbusch's Beethoven monument - I

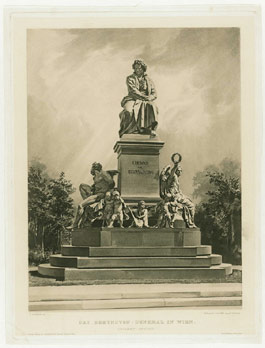

The most famous Beethoven monument from the second half of the 19th century is without doubt the one created by

Caspar Clemens Zumbusch (1830-1915) in Vienna. The tendency to depict Beethoven as a hero and express the

meaning of his music by scores of allegorical figures is even stronger than in Friedrich Drake's draft.

Beethoven monument in Vienna by Caspar Zumbusch (1880)

The composer rests enthroned far away from the beholder on whom he looks down. The front and rear side of the

monument feature puttos at the composer's feet, representing his symphonies or his music in general. Prometheus

and goddess Fama are on the sides of the monument. The entire construction is supported by a three-step

base.

Beethoven monument in Vienna by Caspar Zumbusch (1880)

Beethoven monument in Vienna by Caspar Zumbusch (1880)

1878 - 1880

Caspar Zumbusch's Beethoven monument - II

The Beethoven monument by Caspar Zumbusch was not the first monument for a Vienna musician. In 1862, the Vienna

Male Choral Society had a statue erected for Franz Schubert. It was designed by artists Theophilus Edvard von

Hansen (1813-1891) and Carl Kundmann (1838-1919) and unveiled in 1872.

Beethoven statue of the Beethoven monument in Vienna by Caspar Zumbusch (1880)

In the 1870s Vienna felt a need to finally set up a monument for Ludwig van Beethoven and held a competition.

Well-known artists - particularly Franz Liszt and Johannes Brahms supported the project with generous financial

contributions so that the monument could be presented to the public on May 1st, 1880.

Beethoven monument in Vienna by Caspar Zumbusch (1880)

Schubert monument in Vienna by Carl Kundmann (1842)

The new and special features of Carl Zumbusch's monument become particularly clear when comparing it to the

slightly older Schubert monument from Karl Kundmann. Kundmann also presented the composer in a sitting position

on a high pedestal and wrapped in a large coat. However, his monument is less pompous and conveys a more private

atmosphere. This is mainly due to the pedestal's design which, for the Schubert monument, was decorated with

reliefs, whereas the pedestal of the Beethoven monument features vivid sculptures.

Therefore, Caspar Zumbusch's monument represents the strong self-confidence of the German and Austrian upper

middle classes which regarded themselves as the main supporters of German art during the second half of the 19th

century. In accordance with this conviction, the monument should not only honour an important person but also

adorn the city, as a newspaper article from 1877 says.

Around 1900

From Apollo to Jupiter

The admiration for Beethoven as the epitome of a creative artists hit its peak at the end of the 19th and during

the first third of the 20th century. The heroisation of the composer in fine arts was not restricted to Germany

and Austria but was also expressed in works by French artists and in various monuments erected on the American

continent.

From now on Beethoven was not depicted as a contemporary musician or inspired composer but compared to the

heroically struggling titan Prometheus or even Jupiter, the highest of all gods.

Beethoven high up in the clouds by Adolf Lang (1905)

To express this special admiration for Beethoven, many artists such as Franz von Stuck (1863-1938) or Joseph

Adolf Lang (1873-1928) portrayed the composer on a very high throne. By using plain and blocklike forms, they

tried to give their works a particularly monumental impression to show the distance between the titan

"Beethoven" and the ordinary human being.

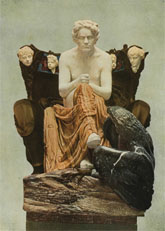

Max Klinger (1857-1920): Beethoven monument in Leipzig (1902)

Max Klinger's Beethoven monument is probably the best example for such late romantic ideas in fine arts. Klinger

(1857-1920) strongly admired Beethoven. He believed that music was clearly superior to sculpture as it depended

less on the material world and was therefore closer to deity than fine arts. Beethoven, who in Klinger's eyes

was the greatest composer, was therefore not just an inspired and creative man. In the artist's opinion, he had

almost become a god and the epitome of an artist.

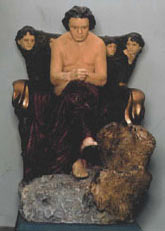

Max Klinger's Beethoven monument

Already in the 1880s Max Klinger, then living in Paris as a student, focused on the project of creating a

monument in honour of Ludwig van Beethoven. As he once said, he had the first ideas for a sculpture when playing

the piano. Thus, the first version of the later monument was born. Klinger then realised his idea in gypsum and

coloured it vividly.

Model of the Beethoven monument in Leipzig by Max Klinger (1885/86)

Max Klinger´s Beethoven monument in Leipzig (1902)

During the decades before 1900, Max Klinger used this model to design a large-format sculpture. He unveiled it

for the first time in public at the exhibition of the Vienna Secession in 1902.

Also Max Klinger depicted Beethoven as a bare-breasted Olympic deity. Thereby, the sculptor alluded to the

ancient way of depicting gods. The large coat that is wrapped around the composer's lower body and the sandals

he wears were designed according to traditions of the ancient world. Beethoven sits on a richly decorated

throne. At his feet rests an eagle, Jupiter's heraldic animal. Beethoven's hands are fisted, his facial

expression seems concentrated and energetic.

Beethoven's "high rank" in Klinger's sculpture is additionally supported by allegorical scenes on the throne's

exterior where the composer is also related to redemption motives taken from Christianity.

Max Klinger´s Beethoven monument at the Vienna Secession Exhibition (1902)

Max Klinger presented his Beethoven sculpture for the first time in public in Vienna in 1902. The room at the

Secession building, where the work was put up for display, features a frieze of figures by Gustav Klimt (1962 -

1918). The unusual sculpture caused a public indignation because it was regarded as inadequate and consequently

met with derision.

Only after quite some years could Klinger sell the sculpture to the city of Leipzig. From then on, his monument

was seen as the ideal of a heroic Beethoven monument, showing the composer as an epitome of the human mind which

can become godlike through achievement.

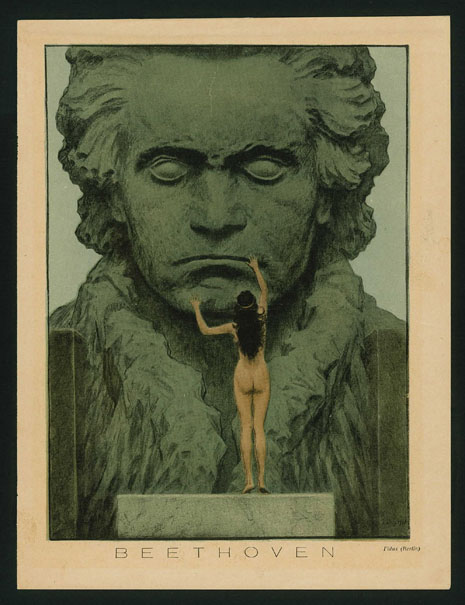

1900 - 1910

Beethoven monuments of the Reform Movements in the early 20th century

Max Klinger was not the only artist of the early 20th century to express his admiration for Beethoven. During

this time a whole range of works was created. Particularly interesting is the project by Fidus, a reform artist,

which is based on a monumental concept.

Whatever activities he engaged in, Fidus always aimed at reforming the modern world's entire worldview and view

of life.

Consequently, he wanted to create alternatives for the power of established occidental churches and

Christianity. From this approach he developed several drafts and concepts for temples to glorify outstanding

achievements and ideas of the occidental culture.

Hugo Höppner, called Fidus: Draft for a Beethoven temple (1903)

His draft for a "Beethoven temple" is to be seen in this context: A rotunda with a cupola and a centre with an

overdimensional Beethoven portrait.

The first draft for this sculpture dates from 1900 and includes a half length portrait of the composer. A naked

female figure - probably the human soul - stands in front of Beethoven.

Just like many other projects, Fidus never realised his draft for a Beethoven temple.

1900 - 1910

Searching for new forms

While Max Klinger and Fidus developed their romantic ideas of Beethoven as a "superman", other artists created

their own concepts for a Beethoven monument. Some of these drafts and models strictly followed the traditional

types and forms of the 19th century. Other artists tried to break new grounds.

Beethoven monument in Heiligenstadt by Robert Weigl (1902-1910)

Martin Tejcek: Beethoven on a walk (1841)

Of particular interest is the Beethoven monument erected by Robert Weigl (1851/52 - 1902) in

Vienna-Heiligenstadt. Weigl's approach was clearly different from the concepts of the late romantics and is more

conform to the naturalistic idea of the mid 19th century.

Weigl used a lithograph by Martin Tejcek (1780 - 1847) that shows Beethoven on a walk as model for his Beethoven

figure. The artist created his sculpture closely following the depicted Beethoven and thus achieved a very

realistic effect. His monument should give the beholder the impression as if he had just met Beethoven on a

walk. Here, Beethoven is shown in an entirely human way.

Only a few years after this sculpture was put up, such a concept was regarded as not monumental enough. As a

consequence, a peripteral enclosure was built around the statue to separate it from the beholder's world.

Beethoven depictions influenced by Auguste Rodin

Antoine Bourdelle - I

In the years around 1900 the admiration for Beethoven reached a special height not only in Germany and Austria

but also in France where men of letters and artists focused on Beethoven and his art. Two artists living in

Paris were especially important for the development of a novel and modern type of monument: Antoine Bourdelle

(1862-1929) and Naoum Aronson (1873-1943). Both were taught by and worked for Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), without

doubt the most important European sculptor of the late 19th century. In their style both artists were strongly

influenced by Rodin's expressive works.

Emile Antoine Bourdelle: "Beethoven au foulard" (around 1890)

Throughout his life, Emile Antoine Bourdelle dealt with Ludwig van Beethoven. He created the first Beethoven

busts in 1889. Until his death in 1929, Bourdelle repeatedly focused on the great composer's personality and

art, creating many designs, models, paintings and sculptures depicting Beethoven. Even today, more than 20

different portraits of the composer painted by Bourdelle exist.

Emile Antoine Bourdelle: "Beethoven" (1902)

Although Bourdelle's admiration for Beethoven was as high as the admiration shown by German late romantics, his

style is entirely different from the way German artists portrayed the composer. Around 1900 at the latest

Bourdelle was not interested in creating Beethoven's realistic looks but preferred a monumental depiction of the

composer, expressing pathos, tragedy and heroic passion. To achieve this effect, Bourdelle used free forms full

of vigorous movement. In their expressivity and passions, these forms are evocative of works by Rodin.

Beethoven depictions influenced by Auguste Rodin

Antoine Bourdelle - II

Bourdelle's fascination for Beethoven continued until the sculptor died. During the last five years of his life,

Bourdelle produced no less than six busts and sculptures showing the composer.

Emile Antoine Bourdelle: "La Pathétique" (1929)

This figure named "La Pathétique" or "Beethoven à la croix" is Bourdelle's last work. It shows how strongly

Beethoven epitomised the suffering and struggling genius in the eyes of the late 19th and early 20th century

artists. The symbol of the cross proves that the composer was not only identified with pagan deities but was

also interpreted as the suffering redeemer in a Christian sense. In this way, Bourdelle's works also express an

intimate avowal of his own self and his self-conception as a creatively working and struggling mind.

Beethoven depictions influenced by Auguste Rodin

Naoum Aronson's Beethoven monument in Bonn

The second student of Rodin who concentrated on designing a monument for Beethoven was the Latvian sculptor

Naoum Aronson (1873-1943).

Naoum Aronson : Beethoven monument in the garden of the Beethoven House in Bonn

(1905)

In the summer of 1905 Naoum Aronson visited the concerts of the seventh Bonn Chamber Music Festival organised by

the Beethoven-House. Under the impression of the performed music, the sculptor already began his first studies

for a Beethoven bust during his visit.

Naoum Aronson: Drafts and models for the Beethoven monument in Bonn (summer 1905)

Shortly later, Aronson produced a monumental gypsum model in Paris. The intensive effect of his Beethoven

portrait is particularly enhanced by the way Beethoven's head is tilted and the clouding of his eyes. The

composer does not face the beholder but averts his gaze and appears as an artist full of passionate ideas but

living in his own world - an opinion totally in line with the ideas of the early 20th century.

Aronson gave his model to the Beethoven-House which appreciated this modern depiction of the composer so much

that it asked Aronson in August 1905 to reproduce the bust in bronze. In the autumn of 1905, a granite pedestal

was made for the sculpture following Aronson's draft. On December 17th, 1905 the monument was finally unveiled

in the garden of the Beethoven-House. There it can still be seen and admired by the museum's visitors.

1920 - 1939

Beethoven monuments between tradition and modernity

The general veneration of Beethoven reached a second peak between 1920 and 1930. On the one hand this was due to

the fact that 1927 was the 100th anniversary of Beethoven's death day. On the other hand, this intensive focus

on Beethoven in Germany was a result of the traumatic experience from the First World War. After the military

defeat, Germany reverted to cultural achievements in order to obtain national self-confidence.

Gosen´s Beethoven monument in Mexico City (1921)

The monuments and monument drafts from this time are characterised by their concepts and style being very

various. They share the intention of depicting Beethoven not so much as a person but instead show his music.

Thus, quite different approaches resulted where Beethoven's artistic achievement was the main subject, whereas

depicting the composer as a person was given less importance.

An example for such an approach is Theodor von Gosen's (1873 - approx. 1925) Beethoven monument in Mexico City.

Allegorical elements, which in the 19thh century were typically part of a monument's pedestal area, became the

most important part of the monument. A winged Genius is placed on a high pedestal. A figure - the suffering

human soul - kneels in front of him and pleads for redemption. Beethoven's mask, which is attached to the

pedestal, clearly suggests the message that redemption can be found in his music.

1926

A Beethoven monument in Berlin

When Berlin arranged a competition regarding a Beethoven monument in 1926, the search for new forms for such a

monument hit another peak. Many famous sculptors submitted drafts and models, among them Ernst Barlach (1870 -

1938) and Georg Kolbe (1877 - 1947). German press amply dealt with the subject and partially severe criticism

was voiced. As opinions among the competition committee members and the press were rather different and as the

entire project was quite controversial, the prize awarding never took place and the plans for a new Beethoven

monument were finally dropped completely.

Only two of the submitted drafts were later carried out as monuments: Georg Kolbe's and Peter Christian Breuer's

(1856 - 1930).

Model for a sitting Beethoven sculpture by Peter Christian Breuer (1910 or 1926)

The Beethoven monument by Breuer, who came from Cologne, has a particularly long and checkered history.

Obviously, Breuer had already dealt with designing a monument for Ludwig van Beethoven around 1910. However, the

draft was not realised. When the Berlin competition took place, Breuer submitted a draft for which he reverted

to his prior ideas.

Peter Christian Breuer (1856-1930): Model for a Beethoven monument (1926)

Peter Christian Breuer (1856-1930): Model for a Beethoven monument (1926-1930)

Now, he designed a vast site composed by architectural elements and various figurative depictions. At its

centre, the monument featured a seated larger-than-life sized Beethoven. After the Berlin monument project was

given up, the city of Bonn raised an interest in Breuer's draft. The sculptor then edited his concept. The

originally planned site should now be smaller and less pompous and be integrated in a park scenery.

1926 - 1938

Peter Christian Breuer's Beethoven monument

Peter Christian Breuer / Friedrich Diederich:

Beethoven sculpture at the Rheinaue in Bonn (1926-1938)

Peter Christian Breuer / Friedrich Diederich:

Beethoven sculpture at the Rheinaue in Bonn (1926-1938)

Eventually, only one element from Breuer's model was actually realised in a larger format. Fritz Diederich, a

long-time assistant of Breuer's created Beethoven's figure in granite. After Breuer's death, the scuplture was

displayed in public at the 'Alte Zoll' in Bonn. In 1949, it was removed and put up for display again in 1977 -

this time at the 'Rheinaue' in Bonn.

Peter Christian Breuer / Friedrich Diederich:

Beethoven sculpture at the Rheinaue in Bonn (1926-1938)

1950 - 2000

A time for experiments - I

Already during the first half of the 20th century, artists designing monuments for Ludwig van Beethoven were

looking for new concepts. As many of the previously accepted forms and subject matters were being questioned due

to the experiences of the Second World War, the search for new concepts even increased in the years after 1945.

This a number of new approaches were developed, quite different in their meaning and style. American sculptor

Eugen Cuica (*1913), for example, chose purely abstract forms to express his veneration of Beethoven's music for

his monuments.

Klaus Kammerichs: "Beethon" - Beethoven monument in front of the Beethoven Hall in

Bonn (1986)

Sculptor Klaus Kammerichs from Düsseldorf went an entirely different way when focusing on Beethoven as a person.

He created a large-format, three-dimensional version of the Beethoven portrait by painter Joseph Karl Stieler

(1781-1858). Stieler's painting from 1820 is now one of the most popular and famous Beethoven depictions of the

19th century.

Ludwig van Beethoven with the manuscript of the Missa Solemnis by Joseph Karl

Stieler (1820)

The monument erected by Klaus Kammerichs in front of the Beethoven Hall in Bonn in 1986 captures the whole basic

difficulty a modern society experiences regarding the exposure to Beethoven as well as its opinion towards

outstanding artists of the past. In his work, Kammerichs related to a portrait that influenced our idea of

Beethoven's appearance like no other portrait. Therefore, the sculptor not only created a monument that looked

familiar but also made it clear how strongly conventions and ideas from the past influence modern society in its

view of Beethoven.

1950 - 2000

A time for experiments - II

For its first public presentation, the Beethoven monument by Klaus Kammerichs was not yet called "Beethon" as it

is today but "Mythos Beethoven" (Beethoven Legend). The monument was created with the intention of expressing

the difficulty that arises when dealing with Beethoven these days.

Klaus Kammerichs: Beethoven monument (front view) in front of the Beethoven Hall in

Bonn (1986)

Klaus Kammerichs: Beethoven monument (rear view) in front of the Beethoven Hall in

Bonn (1986)

The history of the Beethoven monuments of the 19th and 20th century not only mirrors the development of an art

genre but is closely linked to the way how Ludwig van Beethoven was revered during the various epochs. All

monument projects also express the general opinion the broad public had about Beethoven.

The fact that the first efforts to create a monument for the dead composer go back to only a couple of years

after Beethoven died, and that memorials and monuments are still erected, gives clear evidence that the

composer's charisma and the influence of his music still prevail until today. On the other hand, it shows how

strong the general need was and is to honour an outstanding composer with a public monument. We can expect with

great expection how monuments for Beethoven will look like in the third millennium.

Klaus Kammerichs: Beethoven monument (side view) in front of the Beethoven Hall in

Bonn (1986)

Literature

On the topic in general

F. J. Alai: Beethoven glorified in statues. London 2000.

I. Bodsch: 'Monument für Beethoven'. Die Künstlerstandbilder des bürgerlichen Zeitalters als Sinnstifter

nationaler Identität?

in: I. Bodsch (Hrsg.): Monument für Beethoven. Bonn 1995, S. 157-177

R. Cadenbach: Mythos Beethoven. Laaber 1986.

H. Hallensleben: Das Bonner Beethoven-Denkmal als frühes "bürgerliches Standbild"

in: I. Bodsch (Hrsg.): Monument für Beethoven. Bonn 1995, S. 29-37.

J. Schmoll genannt Eisenwerth: Zur Geschichte des Beethovendenkmals

in: Saarbrücker Studien zur Musikwissenschaft. Bd 1. Kassel 1966, S. 242-277.

On individual artists and monuments

S. Einholz: Peter Breuer (1856-1930). Ein Plastiker zwischen Tradition und Moderne.

Phil. Diss. Berlin 1984.

D. Gleisberg (Hrsg.): Max Klinger, 1857-1920. Leipzig 1992.

H. Guratzsch (Hrsg.): Max Klinger. Bestandskatalog der Bildwerke, Gemälde und Zeichnungen im Museum der

bildenden Künste Leipzig. Leipzig 1995.

I. Jianou / M. Dufet: Bourdelle. Paris 1984.

G. Kapner: Ringstraßendenkmäler. Zur Geschichte der Ringstraßendenkmäler. Dokumentation. Wiesbaden 1973.

E.-M. Klother: Emile Antoine Bourdelle: 'Ludwig van Beethoven (Grand Masque Tragique)', 1901

in: Kölner Museums-Bulletin. (2003) 4, S. 13-22.

H. Loos: Max Klinger und das Bild des Komponisten

in: Imago Musicae. 13 (1996), S. 165-188.

P. Naredi-Rainer: Granitstarker Klang. Max Klingers "Beethoven", die Musik Gustav Mahlers

und die Sprache der Materialien

in: P. Naredi-Rainer (Hrsg.): Imitatio. Berlin 2001, S. 218- 227.

S. Schaal: Das Beethovendenkmal von Ernst Julius Hähnel in Bonn

in: I. Bodsch (Hrsg.): Monument für Beethoven. Bonn 1995, S. 39-134.

R. Y: Fidus, der Tempelkünstler. T. 1.2. Göppingen 1985.

Legal notice

Publisher:

Beethoven-Haus Bonn

Bonngasse 24-26

D-53111 Bonn

Germany

Texts:

Dr. Silke Bettermann