What happened before

Johann Peter Salomon smooths the way

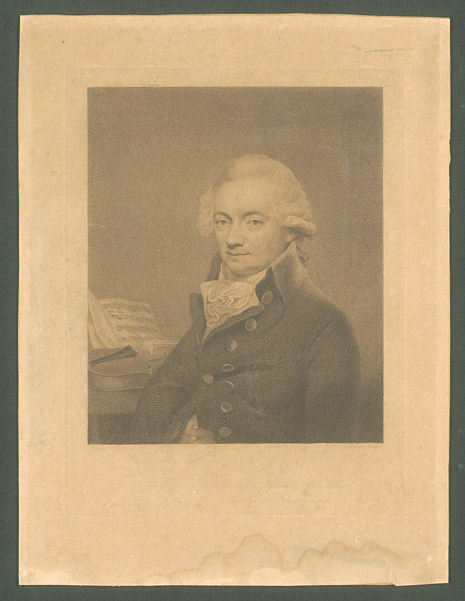

Just like Beethoven, violin player Johann Peter Salomon (1745–1815) was born in Bonn and grew up in the

Beethoven-Haus of today. 24 years later he was also admitted as a 13 year old to the

Prince-Elector's Bonn Court Chapel, as Beethoven was. Later Salomon became Concert Master serving Prince Heinrich of Prussia.

Around 1780 he settled in London where he played a major role in musical life until his death. As violin

virtuoso, orchestra director and concert entrepreneur he had much success and also belonged to the founders of

the Philharmonic Society. Together with George Smart and Ferdinand Ries Salomon promoted Beethoven's music in

England. He later occasionally engaged in correspondence with Beethoven in Vienna concerning possible publication of Beethoven's music.

When Salomon died, Beethoven was very moved: "Salomon's death inflicts pain on me because he was a noble man whom

I remember from my childhood days."

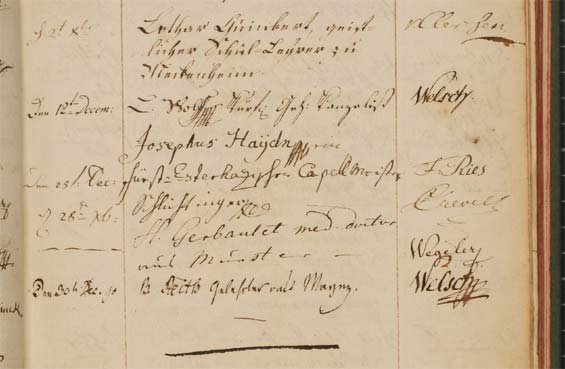

Guest book of the Bonn Reading Society, 1788–1821 Lese- und Erholungsgesellschaft

Bonn

During his successful activity as head-hunter, Salomon managed to bring the renowned Joseph Haydn from Vienna to

the British centre of music twice, namely in 1791/92 and 1794/95. This achievement is even mentioned on his tomb-stone

: "He brought Haydn to England in 1791 and 1794". On their first journey together they passed through his

hometown of Bonn where some of his relatives still lived. On Christmas Day in 1790 Beethoven's violin teacher

Franz Anton Ries introduced Joseph Haydn as a guest to the "Lesegesellschaft" (reading society) founded three

years earlier. Certainly, Salomon, who on his outward journey had attended the reading society on October 1 in the

company of two guests from London, was there, too. Hence on this occasion Beethoven not only met his future

teacher but also made a first contact with England, although in a less direct way.

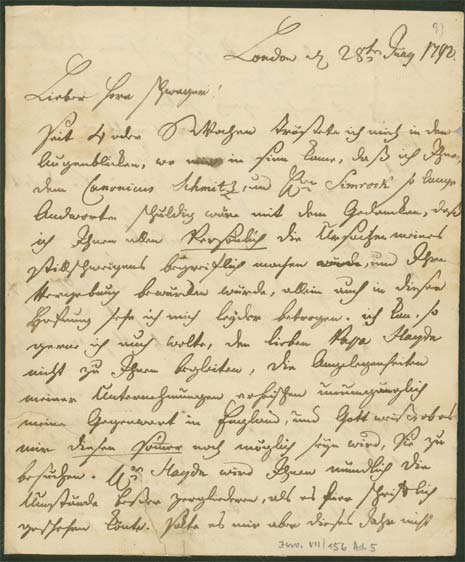

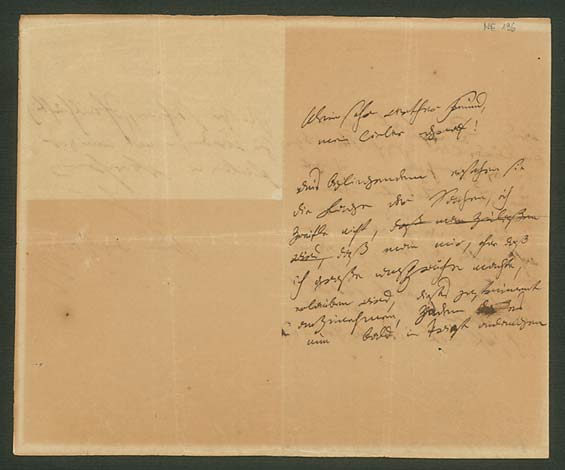

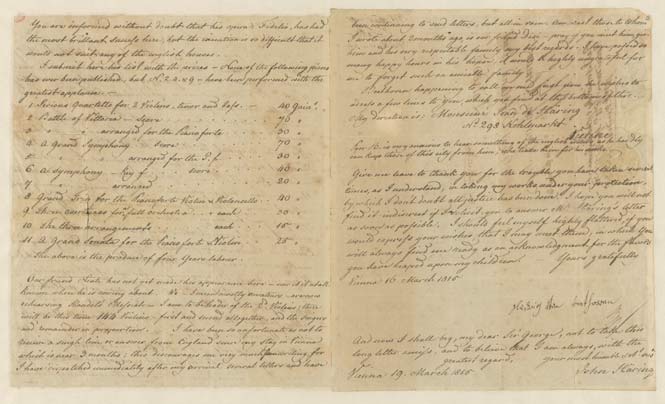

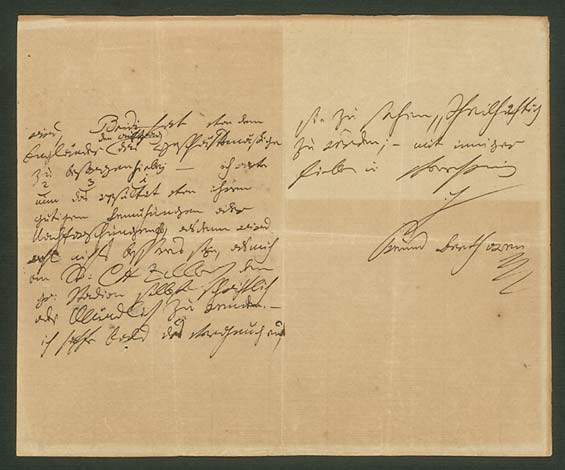

Letter from June 28th, 1792

Salomon was not able to accompany Haydn on his journey back home in 1792. In a

letter to his brother-in-law Geiger in Bonn he expresses his regret: "As much as I wanted I am not able to

accompany dear father Haydn on his way to you, because the matters of my business are calling for my presence in

England. Mr. Haydn will tell you the reasons better." The expression "father Haydn" both shows a particular

closeness as well as respect. The letter also says that Salomon purchased the piano extracts of two operas by

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart from Bonn publisher Nikolaus Simrock.

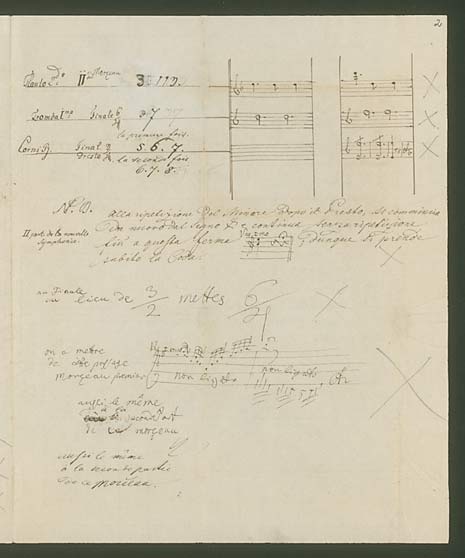

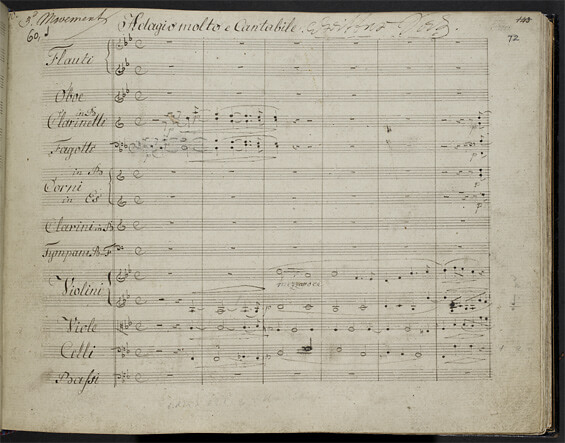

Transformation of the "Military Symphony" for piano trio

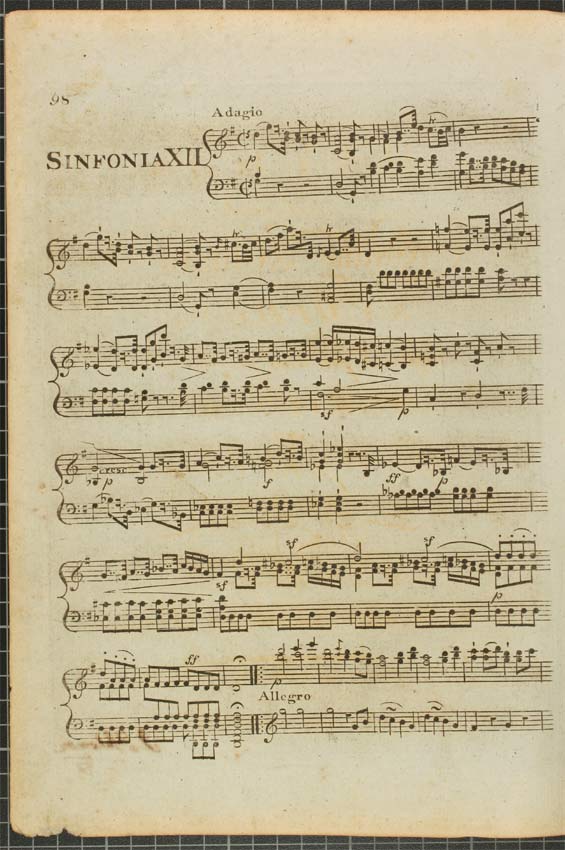

Haydn wrote his last twelve symphonies – still referred to as the "London Symphonies" – for Salomon and his

concert series. According to the agreement the composer ceased all rights thereof to Salomon. Salomon then

adapted the pieces for chamber music instrumentation and published them in his own publishing house even before

the first publication of the orchestra parts. The transformation of Haydn's "Military Symphony" No. 100 for piano

trio bears Salomon's hand-written name on the cover sheet.

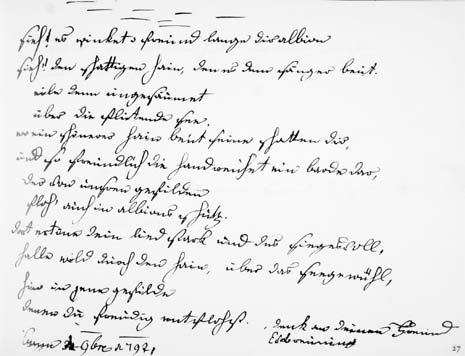

Entry of Christoph von Breuning, October 28th, 1792 Original: Österreichische

Nationalbibliothek, Wien

Thanks to a grant of the Prince-Elector, when Beethoven left Bonn in 1792 like Salomon 27 years ago to take

lessons with Haydn in Vienna, his Bonn friends gave him a "book of memories" filled with good wishes for his

future as a farewell gift. Christoph von Breuning's farewell greeting indicated Beethoven

would also travel to London: "Look! Long time, my friend, Albion [ancient name for the British Isles] has been

waiting for you, see the shady groves it offers the singer" ("sieh! Es winket Freund lange dir albion / sieh!

den schattigen Hain, den es dem Sänger beut"). When Haydn travelled to London for his second visit in

1794/95 one wondered whether the young Beethoven would accompany his teacher. However, Beethoven remained in Vienna,

and even in the future he would never set his foot on London soil.

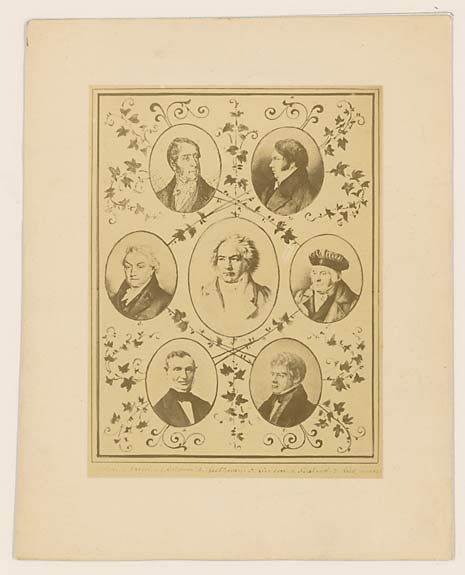

Ornamented sheet with Bonn musicians

Another Bonn native, Ferdinand Ries (1784–1838), son of Beethoven's violin teacher Franz Anton Ries (who once was

a pupil of Salomon), followed Beethoven to Vienna in early 1803 and became his piano pupil. A few years later he

travelled around the world as a piano player and settled in London in 1813. After only two years he was named a

director of the Philharmonic Society. Although in this position he was able to regularly promote the

presentation of Beethoven's works in London, he did not manage to bring the composer to London. Out of the seven

Bonn musicians depicted on the ornamented sheet, three (Beethoven, Salomon and Ferdinand Ries) significantly

influenced musical life in England in the first third of the 19th century.

Beethoven's relationship to Great Britain

Folk song collector George Thomson

George Thomson (1757–1815), a public servant and passionate folk song collector living in Edinburgh, strove to

save the folk melodies of his home country from falling into oblivion. His suggestion directed to Beethoven to

compose six sonatas about Scottish melodies marks the beginning of Beethoven's evident relationship to Britain.

Beethoven's reply letter dated October 5th, 1803 is the composer's first letter across the Channel. Although the

project was never carried out because the parties involved were not able to come to an agreement, a vivid

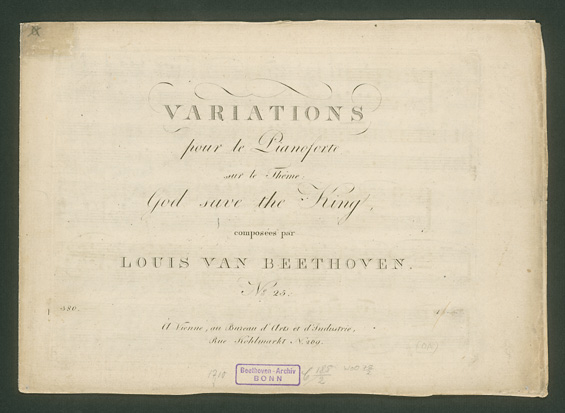

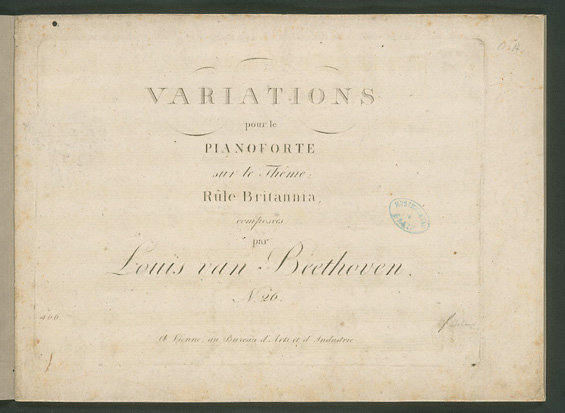

business contact developed until 1820. At the end of October Beethoven offered the piano variations on the

English folk songs "God save the King" and "Rule Britannia," WoO 78 and 79 for printing. "Je vous envoie ci

joint des Variations sur 2 thêmes anglais, qui sont bien faciles et qui, à ce que j'espère, auront un bons

succès." With his suggestion Thomson might have initiated the composition of the variations on this melody

that even people on the Continent knew and cherished. Both pieces were first published in Vienna. Half a year

later Clementi published "God save the King" in London but it took two decades for "Rule Britannia" to be

published by an English publishing house. Beethoven used both melodies again in 1813 for his "Grand Battle

Symphony," op. 91.

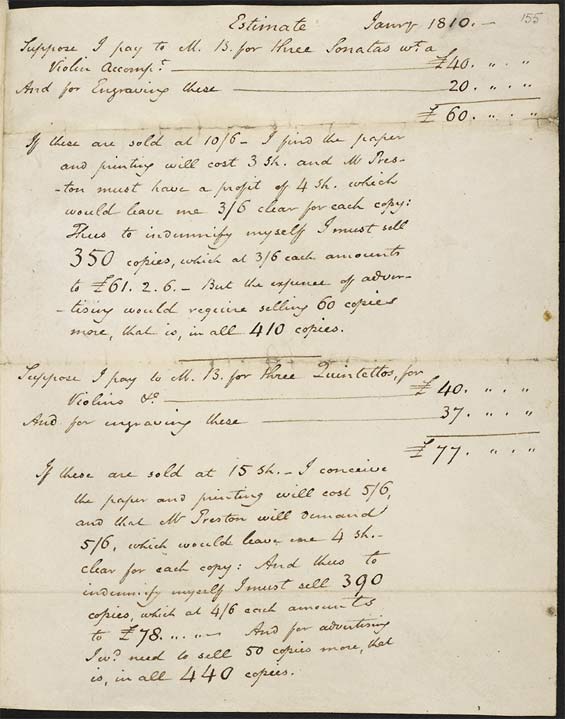

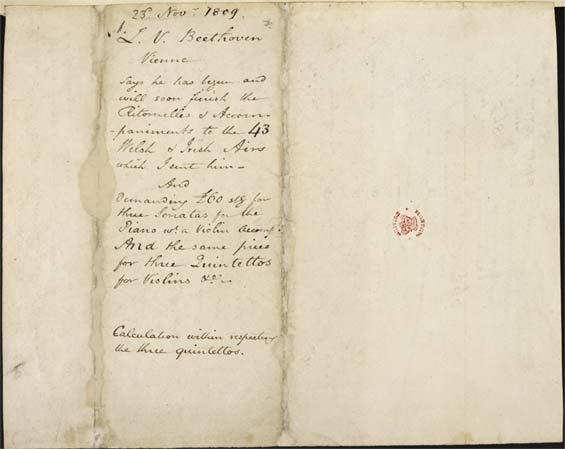

As a result of Beethoven's letter dated November 23rd, 1809 George Thomson drew up the following calculation.

Thomson had offered Beethoven 60 Pounds Sterling (equal to 120 gold ducats) for three quintets and three

sonatas, but the composer demanded double the sum due to the weak exchange rate and the difficult war-induced

situation. For each work category Thomson now earmarked a remuneration of 40 Pounds instead of the offered 30

Pounds (an envelope at the British Library addressed to him shows another calculation on the inside stating 50

Pounds). Thomson calculated that only with 410 and 440 copies sold would the costs be covered. As he considered

the deal too risky, it was never closed.

On the back of the calculation Thomson briefly summarised Beethoven's letter in which the composer also wrote

that he was working on the 43 songs Thomson had sent.

Calculation, January 1810 The British Library

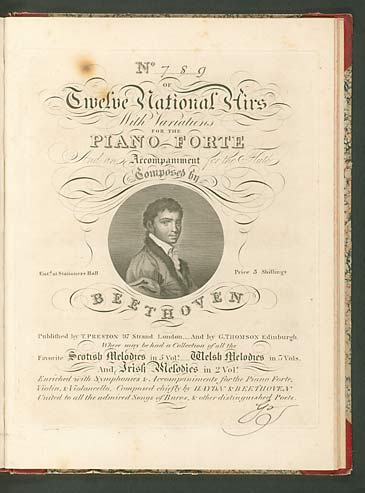

Thomson hoped to increase the folk melodies' popularity by means of a contemporary composition. By adapting the

pieces for piano trio– then popular for making music at home –he wanted to give the British bourgeoisie an

insight into "original" music. He ordered these arrangements from renowned composers such as Joseph Haydn,

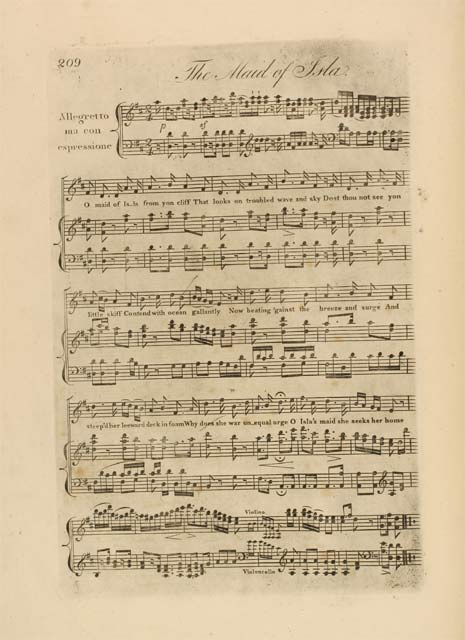

Leopold Kozeluch, Ignaz Pleyel and Beethoven. All in all 150 song arrangements by Beethoven of Irish, Welsh and

Scottish songs have been preserved. In September 1809 Thomson had sent Beethoven 43 melodies and explicitly

asked for an easy piano part. He would do so repeatedly in the future. In the mentioned letter dated November

23rd Beethoven pointed out that this was a less pleasant task for an artist but surely good for business.

Initially he received three ducats for each arrangement, later on four and then five. He also asked to obtain the

texts in the future, a request Thomson did and could not fulfil. The text is not identical with that of the

original folk songs but Thomson had famous poets such as Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott write new lines for

the completed arrangements. In July 1810 Beethoven sent the final 53 arrangements each consisting of three copies

(one by himself and two by copyists) to England by various means. Thomson, however, waited in vain. The present

copy was a gift from Beethoven to his pupil Archduke Rudolph. In the summer of 1811 he borrowed it to make a new

one for Thomson. The receipt of this copy was confirmed in early August 1812.

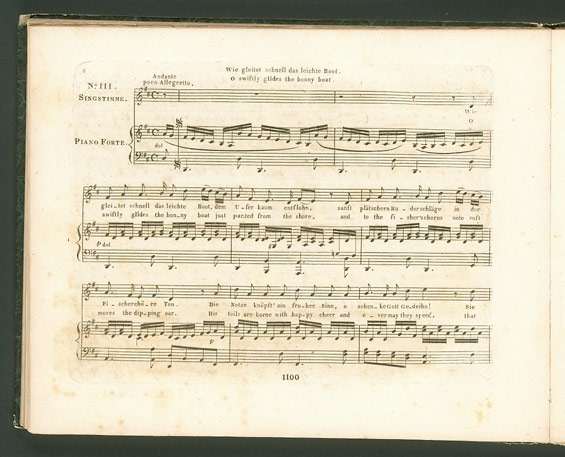

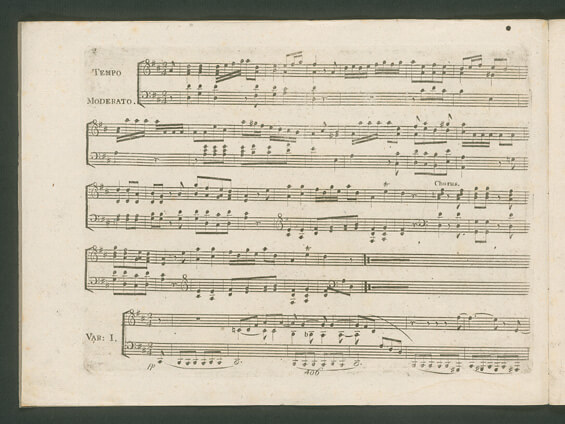

Corrected copy of the 53 folk song arrangements for singing voice, violin,

violoncello and piano, 1810

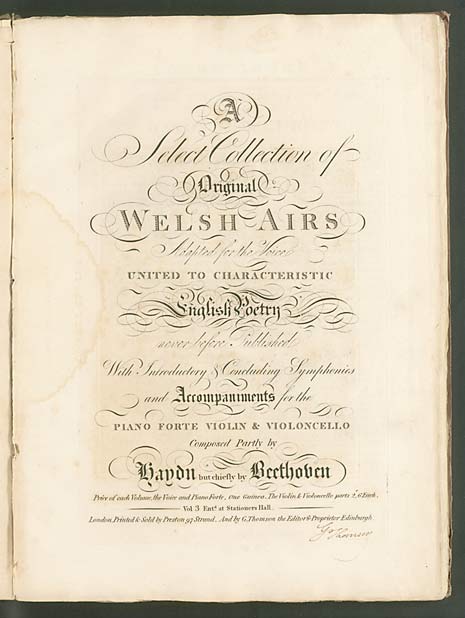

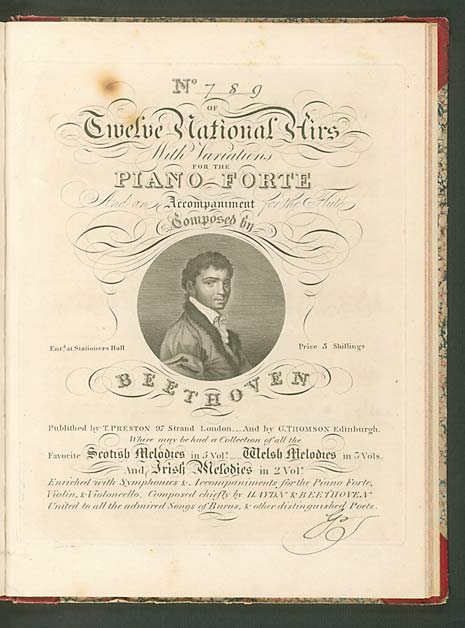

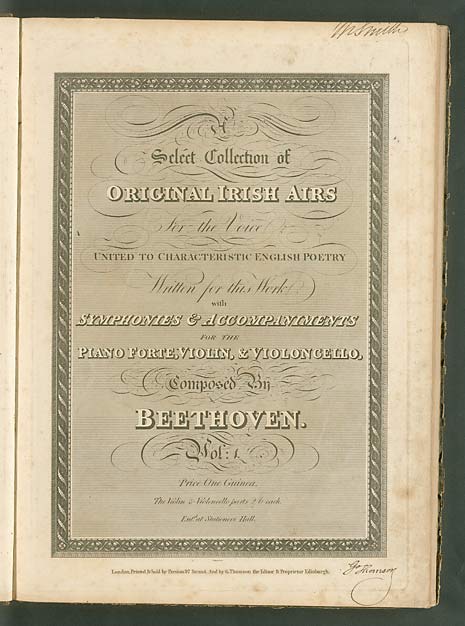

In 1814 the first of two volumes of the "Irish Songs" and in 1817 the third and last volume of the "Welsh Songs"

with Beethoven's contribution were published. Thomson served as editor and the London music publishing house

Preston printed and marketed the folk song arrangements. The book-friendly folio format editions feature

elaborate copper engravings.

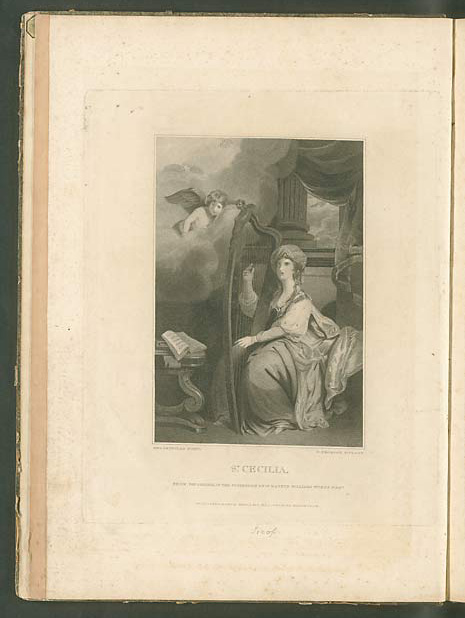

Frontispiece "St. Cecilia" of the 1st volume of the "Irish Songs"

Original edition of the "Welsh Songs", Volume 3, 1817

Beethoven's relationship to Great Britain

Folk song collector George Thomson

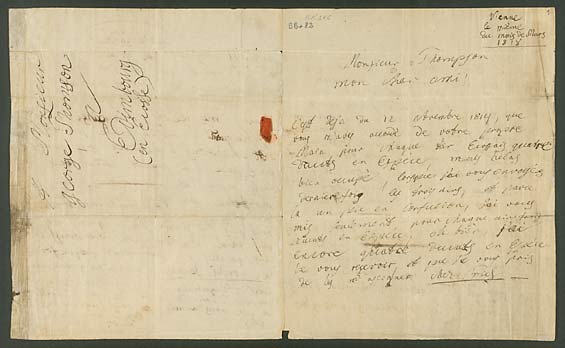

After agreeing on a remuneration of four ducats for each song arrangement in 1814 Beethoven requested a subsequent

payment for three Scottish songs delivered later (Thomson regularly asked Beethoven to simplify his arrangements). In a letter from March 1818 Beethoven claimed he had only received three ducats instead of the

determined remuneration. Thomson, however, replied that the bill issued by the Fries bank certainly stated 12

ducats. Either Beethoven was mistaken or Fries had written the bill only after Beethoven had asked him to do

so.

Beethoven also mentioned that he had the English texts translated, thus it can only be pieces that were

already published in the "Irish Songs" or "Welsh Songs". Probably the translations were done for a planned

publication by the Vienna publisher Steiner. Beethoven offered Thomson piano variations on these melodies at a

price of nine ducats each.

Letter to George Thomson dated March 11th, 1818

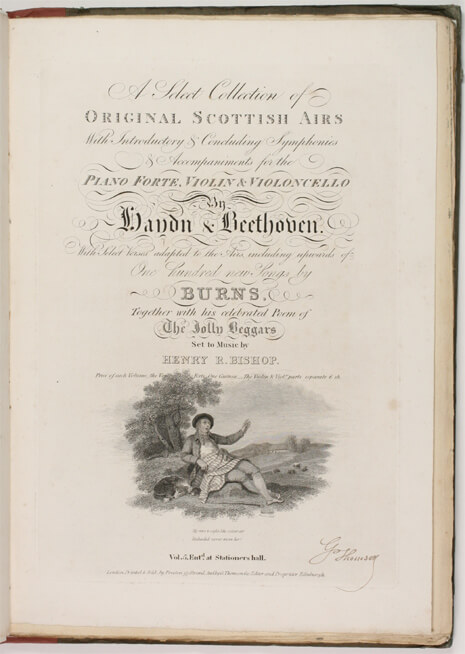

In addition to Beethoven's 25 Scottish songs op. 108, the fifth and last volume of the "Scottish Songs" series published in 1818 contains four songs by Joseph Haydn and the quite popular cantata "The Jolly Beggars" by Robert Burns with a melody by Henry Rowley Bishop. Beethoven had rejected the composition before. Thomson had asked

both to compose the violin part in such a way that it could also be played with a flute. He hoped this would

increase sales. The sales of Beethoven's song arrangements were far below the sales of the first editions

featuring arrangements by Haydn and Kozeluch. The editor believed Beethoven's complex style was the reason for

the decreased revenue. In his last letter to Thomson from May 1819 Beethoven, now angry at Thomson for his

ongoing request for simplicity, explained that he could not regard this as a criterion and that he hardly found

the courage to call the pieces his own.

Original edition of the "Scottish Songs", 5th volume, 1818

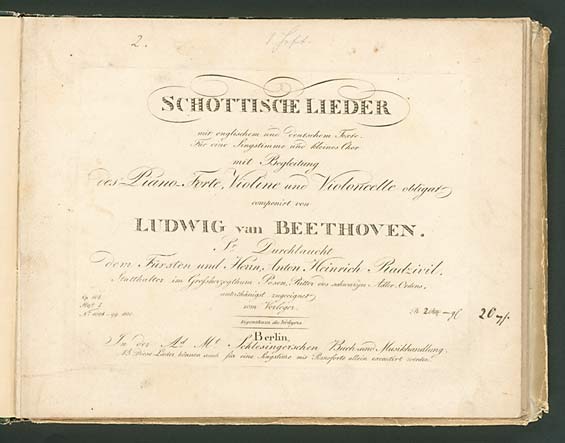

As already mentioned Beethoven, who was quite the adept businessman in using his compositions several times, later

tried to sell the compositions also on the Continent. He did so in Berlin in 1820. Publisher Adolph Martin

Schlesinger showed an interest in the songs and arranged a German edition in 1822. One copy created by two

different copyists, reviewed and corrected by Beethoven, was used for the engraving. Franz Oliva, a friend of

Beethoven and his voluntary secretary, underlaid the English text of the songs. Schlesinger commissioned Samuel

Heinrich Spiker, publisher and librarian of the Berlin Royal University, to translate the text into German for

later addition.

Corrected copy of the Scottish songs for voice, piano, violin and violoncello, op.

108 for the German edition

To facilitate the promotion of the songs in the German market Schlesinger had the edition be printed bilingual in

English and German. Originally, the songs were written in a Scottish dialect, something which did not make

translating them an easy task. Thus, the German translation is not always the best. Beethoven recommended

Schlesinger to commission Carl Friedrich Zelter, a close friend of Goethe, to correct the translations but the

publisher decided in favour of the original.

Bilingual edition of the "Scottish Songs," op. 108

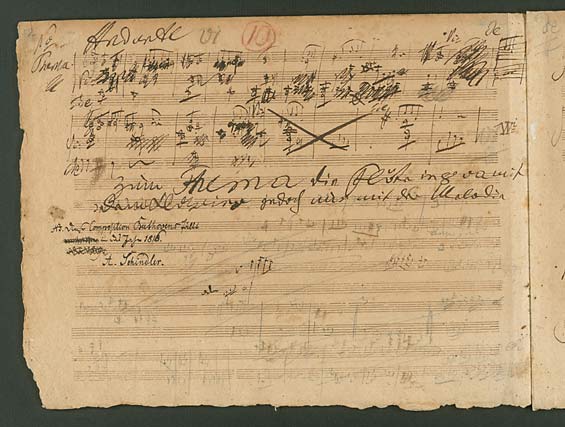

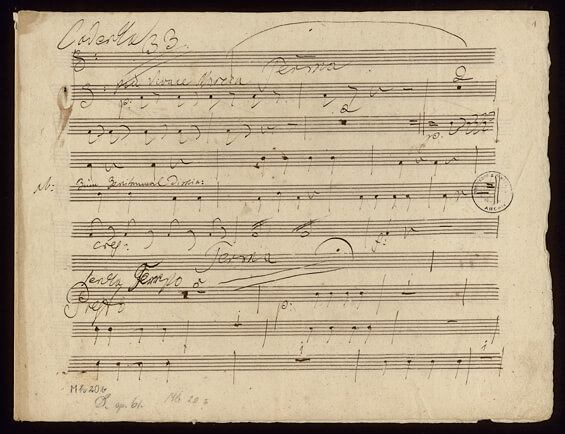

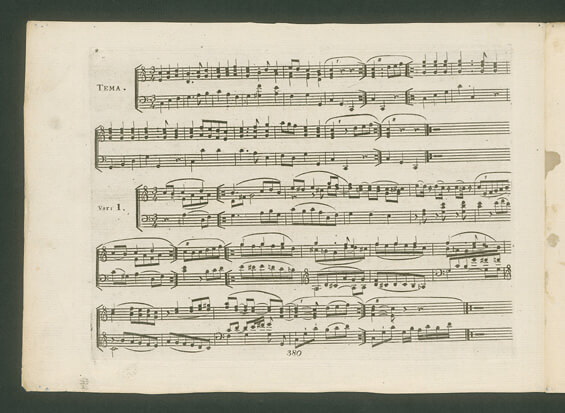

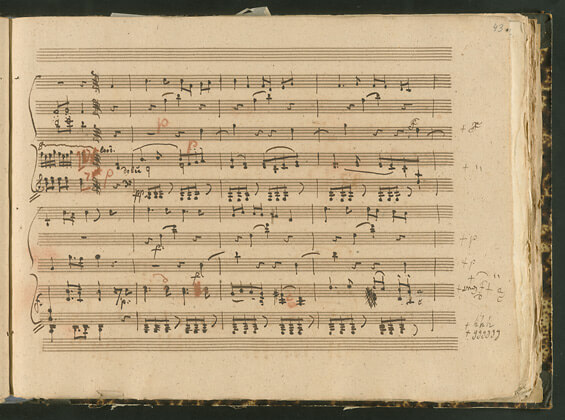

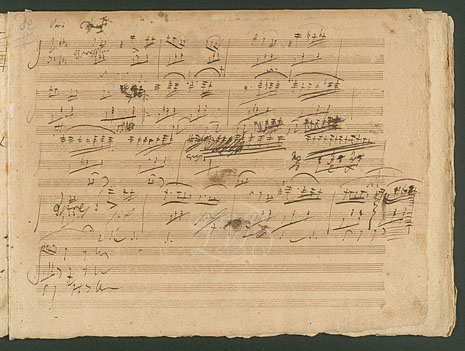

During the arrangement of the folk songs Thomson had asked the composer to include a few European melodies. However, it proved impossible to underlay these with English poetry. In 1818 Thomson commissioned

Beethoven to compose variation cycles for piano and flute on some of these and other subjects that had

partially been published as song arrangement before (op. 105 and op. 107). Displayed are Russian subject

"Beautiful Minka" and the first variation on the Welsh melody "Peggy's Daughter". Beethoven wrote: "for the

theme the flute plays in 8va with the piano but only the melody" ("zum Thema die Flöte in 8va mit dem Klawier

jedoch nur mit der Melodie"), wherever the flute is not mentioned it plays the piano's melody part. The note in the margin is from Beethoven's secretary Anton Schindler who dated the handwriting too early: "This

composition by Beethoven dates [crossed out: "either"] from 1816. [crossed out: "or 1819"] A. Schindler." ("Nb.

Diese Komposition Beethovens fällt [crossed out: "entweder"] in das Jahr 1816. [crossed out: "oder 1819"] A.

Schindler.")

Autograph of the variations op. 107 No. 6 and 7, subject "Beautiful Minka"

In 1819 Thomson published nine of the delivered piano variations. According to the title 12 were planned

originally. The collection was published in three books richly adorned with copper. It contains three Irish,

three Welsh (among them as No. 8 the subject shown above), one Scottish, one Austrian and one Russian subject

("Beautiful Minka" as No. 7).

Variation subjects for piano and flute, 1819

Beethoven's relationship to Great Britain

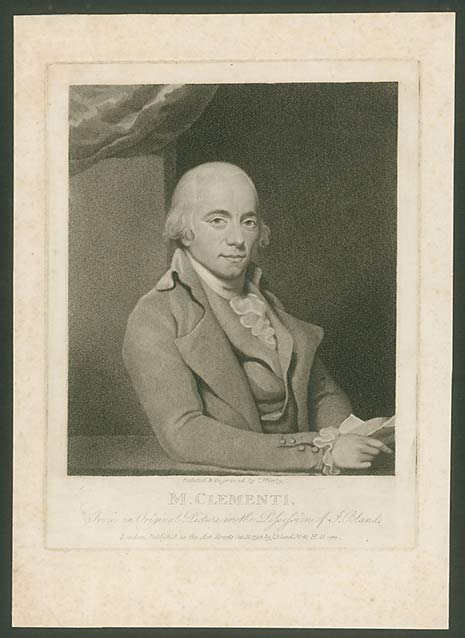

Composer and publisher Muzio Clementi

Muzio Clementi (1752–1832)

Already at the age of thirteen, Muzio Clementi, born in Rome in 1752, was "bought" for seven years by an English

traveller who noticed Clementi's exceptional talent as organ and harpsichord player, and spent this time on an

English country estate, deeply involved in studies. From 1774 he lived in London where he performed stirring

piano sonatas in concerts, something still quite unusual at that time. In the following years he made himself a

name in the London musical life as piano player and teacher. In the early 1780s Clementi undertook a long concert

journey through Europe. Later he also worked as a music publisher and piano manufacturer. In 1798 the famous

piano factory "Longman & Broderip" was renamed "Clementi & Co.". With Clementi as director the company not

only built pianos but also published works written by all famous musicians of that time. When the Philharmonic

Society was founded in 1813, Clementi was named one of the six directors and often took part in their concerts

with great passion.

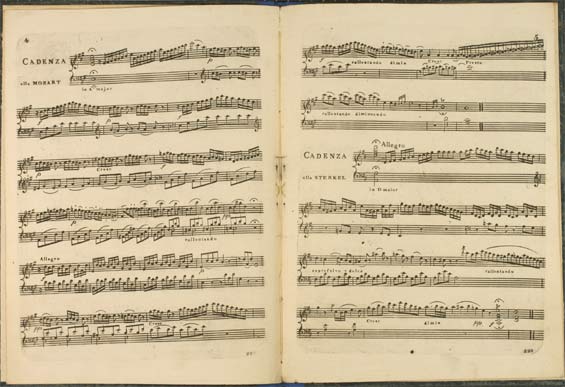

Cadenzas for piano concerts, composed in the style of famous composers, André,

Offenbach 1787

The cadenzas, composed in the style of renowned composers Joseph Haydn, Leopold Kozeluch, Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart, Franz Xaver Sterkel and Johann Baptist Vanhal and complemented by an individual one, represent a

type of musical anthology that should clearly demonstrate Clementi's knowledge of the works of his fellow

composers as well as his own musical flexibility. On Christmas Eve of 1782 Clementi competed with Mozart in a

musical competition in the presence of Emperor Joseph II and the Russian Tsar Paul I without suffering any

damage to his name. At that time cadenzas were only noted and printed with exceptions. Hence, the collection is

of historical relevance as it shows the rewritten text that served as a pattern for cadenzas. Beethoven

with his very individual, if not to say revolutionary cadenzas would have quickly shown any contemporary

imitating this style his limits.

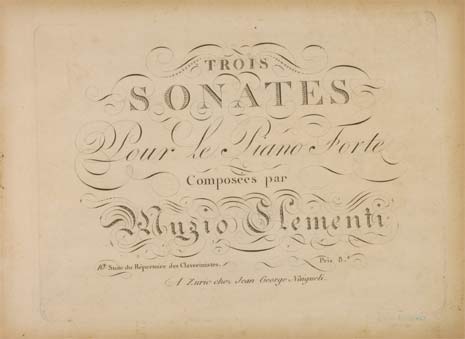

Three Piano Sonatas op. 25

The sonatas op. 25 were published in 1804 as "10. Suite du Répertoire des Clavecinistes," a series edited by the

Zurich publishing composer Johann Georg Nägeli. The ensuing eleven delivery then contained Beethoven's Sonata

"Pathétique," op. 13 and the first print of the Sonata in E flat Major op. 31 No. 3. From a publisher's point of

view, Clementi and Beethoven were then on a comparable level. In his piano sonatas the elder now and then

elaborated on approaches for the future which the younger must have studied with attention during his first

years in Vienna. Later Clementi self-confidently added a selection from his over fifty-year-long working life to

the fairly well-known piano study programme with the sophisticated title of "Gradus ad Parnassum, or The Art of

Playing on the Piano".

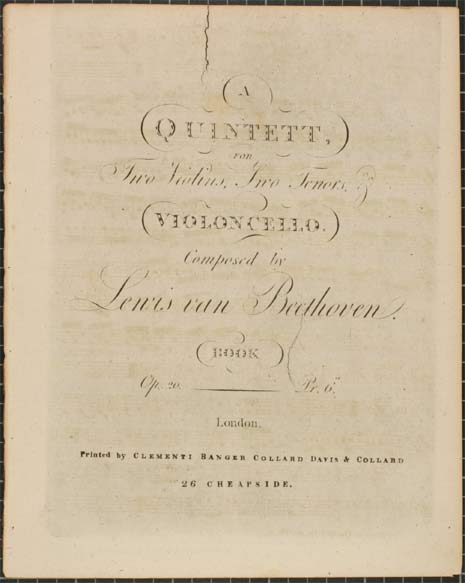

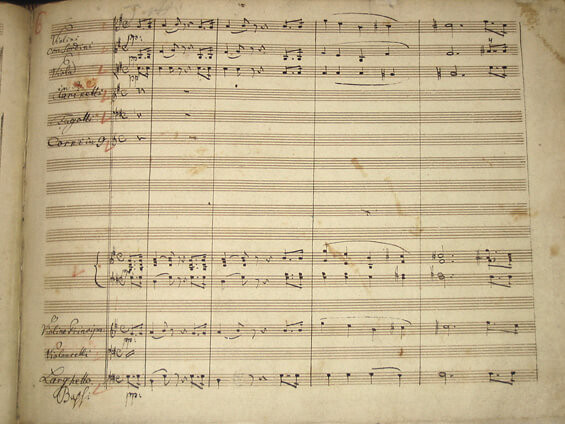

Ludwig van Beethoven, septet op. 20 in a string quintet arrangement

The copy is a later edition of the reprint by Clementi, Banger, Hyde, Collard & Davis dated 1807. The septet's

original edition was published by the Franz Anton Hoffmeister publishing house in Vienna and Leipzig in 1802. In

an announcement in the Vienna newspaper, Beethoven explicitly wrote that only the publisher was responsible for

the transformation into a smaller instrumentation deemed only for string instruments. The visible plate cracks

on the title page, a sign of wear, prove that many copies of this edition were printed which in turn indicates that

the quintet was also very popular in England.

From 1802 until 1810 Clementi went on a long journey to the Continent, selling his own and other works to

publishers and accepting the works of other composers for publishing purposes. In April 1807 he met Beethoven in

Vienna. In a letter to his business partner Collard he described the meeting: according to Clementi, Beethoven

started grinning at Clementi in public places. Of course, he tried hard not to discourage the young composer.

Finally, he was able to conquer the "haughty beauty Beethoven", a term that may be interpreted in various ways

and encompasses various meanings from "proud" to "noble" to "arrogant". When Clementi first visited Beethoven at

his place, he praised some of his compositions effusively and was able finally to conclude an agreement covering

the following pieces: the 4th Piano Concerto op. 58, the Three String Quartets op. 59, the 4th Symphony op. 60,

the Violin Concerto op. 61 and an arrangement of the piano concerto as well as the "Coriolan" Overture, op. 62.

Beethoven received 200 Pounds. However, only the string quartets and the violin concerto, i.e. the arrangement

thereof which Clementi had suggested himself, were later printed. Although Beethoven gave notice when the Vienna

editions were published to facilitate the simultaneous edition of the English editions, those were printed with

a delay of two years.

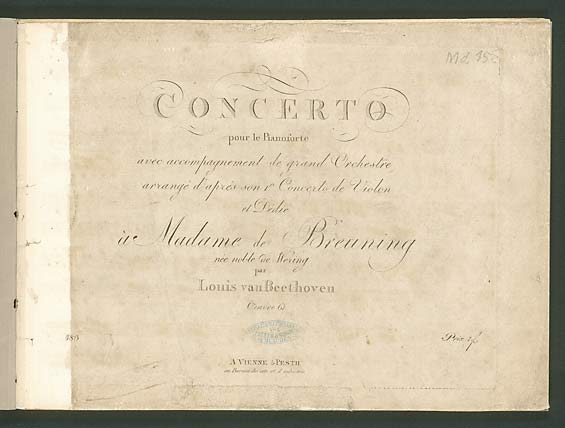

Piano version of the Violin Concerto in (D Major) op. 61, Royal College of Music, London

Beethoven made the piano arrangement possibly with the support of an assistant - on Clementi's request which was

published at the same time as the original version. Today, only one single copy remains and is now in possession

of the Royal College of Music in London. In the field of concertos the piano version did break any ground.

Its purpose is more of a "second use," intended for rather than artistic beliefs. In any

case Beethoven wrote the piano version "for" piano player Clementi and not for use within his own concerts.

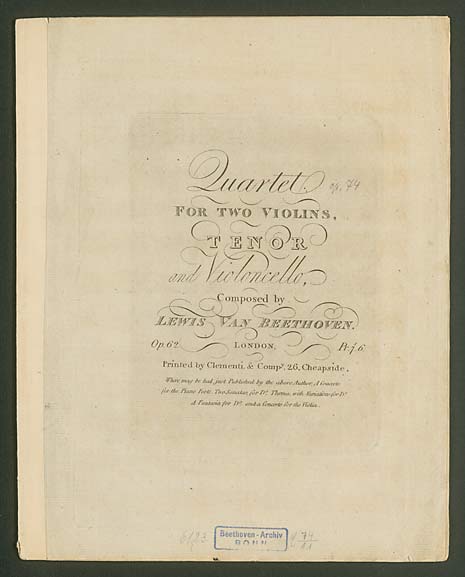

In 1810/11 Beethoven's opp. 73 to 82 were published as "first" original editions. All were published shortly

before the German parallel editions by Breitkopf & Härtel. The string quartet, op. 74, was edited two months

earlier. The title cover explicitly mentions the other Beethoven editions published only a short time before:

"Where may be had just Published by the above Author, A Concerto / for the Piano Forte. Two Sonatas, for D°.

Thema, with Variations for D°. / A Fantasia for D°. and a Concerto for the Violin." Meant here are the piano

versions of the Violin Concerto, op. 61, the Piano Sonatas opp. 78 and 79, the Piano Variations op. 76, the Piano

Fantasy op. 77 and the original version of the Violin Concerto. Here, the string quartet is labelled with opus

number 62 because Clementi continued counting from his last Beethoven edition. The piano sonatas were then

published as op. 63, the Piano Concerto, op. 73, as op. 64 and the Choral Fantasy, op. 80, as op. 65. The other

editions did not have an opus number.

String quartet (E flat Major) op. 74

Composer and publisher Muzio Clementi

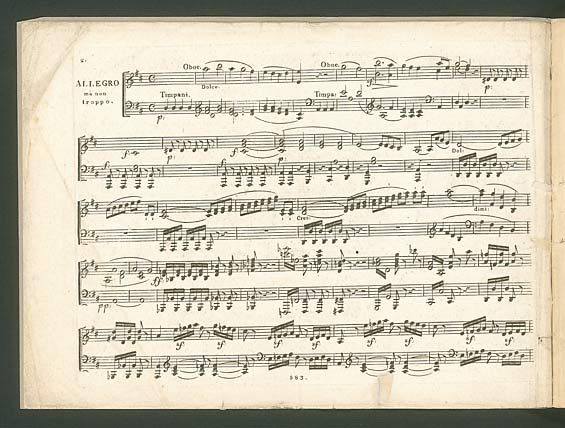

Piano arrangement of the Violin Concerto (D Major) op. 61

One copy of the piano version published by Clementi and thoroughly revised by Beethoven still exists. The

composer corrected notes, added dynamic marking, legato makings, pedal and performance instructions such as

"dolce" and "pizz[icato]," missing clefs, pauses etc. The solo part shows signs of scraping. Many corrections

are indicated with a little cross on the margin.

Copyist's score of the piano arrangement of the Violin Concerto (D Major) op. 61

corrected by the composer

The British Library

During the piano transformation Beethoven also reviewed the part of the solo violin between May and June 1807.

The piano and orchestra version was printed in August 1808, three months later than the "original

version" for violin and orchestra. Whereas the piano arrangement probably never would have been created without the

suggestion of the English publishing house, the London edition was published only after two years.

Piano version of the Violin Concerto (D Major) op. 61

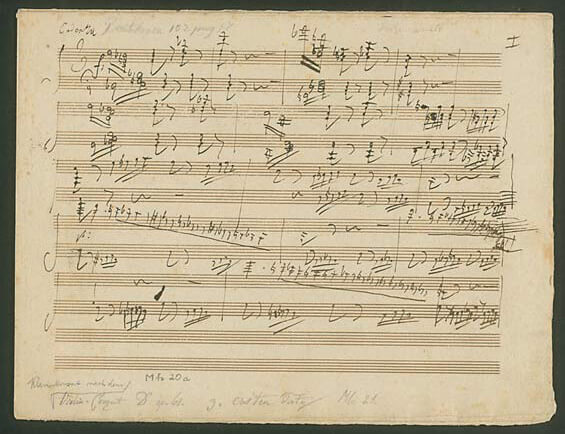

Whereas only one copyist's score corrected by Beethoven of the arrangement remains, original cadenzas written by

him for this concerto have been preserved. Displayed is the cadenza for the first movement. The

length is rather unusual – 12 handwritten pages! In a second version, a part for timpani, was added to the

piano part. To accompany the solo piano part with timpani when playing the cadenza is something unheard of in

piano literature (until Alexander Glaszunov did it again many decades later). Already at the beginning of the

concerto the timpani have a prominent function: with four strikes it opens the work. Maybe Beethoven

wanted to strengthen and confirm this role in the cadenza. In the past, the handwritten cadenza was part of the

musical collection of Beethoven's pupil Archduke Rudolph of Austria, a fine piano player.

Beethoven's own cadenza, piano part

Beethoven's own cadenza, kettledrum part

Beethoven's relationship to Great Britain

Publisher Robert Birchall

After having sold a total of 13 works to the Vienna publisher Sigmund Anton Steiner in early 1815, Beethoven

tried to arrange for a parallel English edition for these pieces, too. A request directed to Sir George Smart in

this matter remained unanswered. Two and a half months later Beethoven offered the compositions to Johann Peter

Salomon in order to bring them to an English publisher (both letters are shown on the following pages). Salomon

managed to sell at least four pieces: for 130 Dutch gold ducats London publisher Robert Birchall bought the

Violin Sonata op. 96, the "Archduke Trio," op. 97 and the piano extracts of the Seventh Symphony op. 92 and of

the "Grand Battle Symphony", op. 91. Beethoven's former pupil and friend Ferdinand Ries who spent ten years of

his life in London, carried out the corrections for Birchall and settled further details between composer and

publisher such as publication dates.

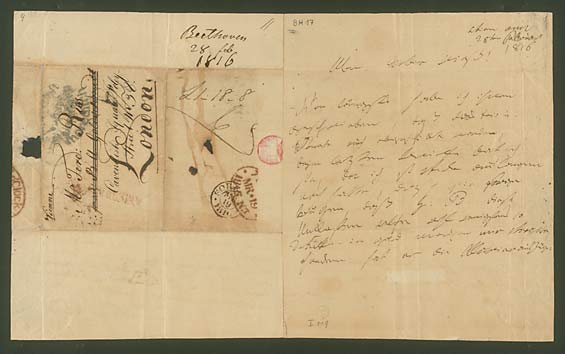

Letter to Ferdinand Ries in London, February 28th, 1816

In the meantime Beethoven had sent all four compositions to London and now requested the publisher reimburse

him for the costs for copying and postage in addition to his payment. ("It is very little for an Englishman but a

lot more for a poor Austrian musician!"). On February 10th he sent Ries a detailed bill stating additional

expenses of ten ducats. Besides, he expressed his sorrows about Salomon's death for whom Ries served as executor

of his will: "Salomon's death inflicts pain on me because he was a noble man whom I remember from my childhood

days."

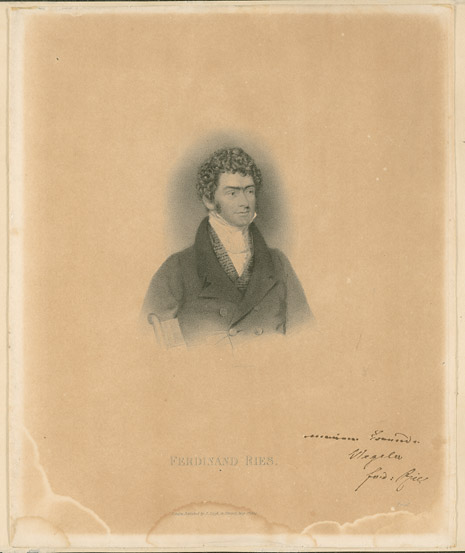

Ferdinand Ries (1784–1838)

In 1824 Ries returned to the Rhineland. Shortly before, this portrait was created and published in the English

music magazine "The Harmonicon". Ries gave a copy to his old Bonn friend Franz Gerhard Wegeler (1765–1848) as a gift

and added the following handwritten dedication: "to my friend Wegeler Ferd: Ries" ("meinem Freunde Wegeler Ferd:

Ries"). The title quote of the exhibition "Where your compositions are preferred to any other" was taken from a

letter from Ferdinand Ries to Beethoven.

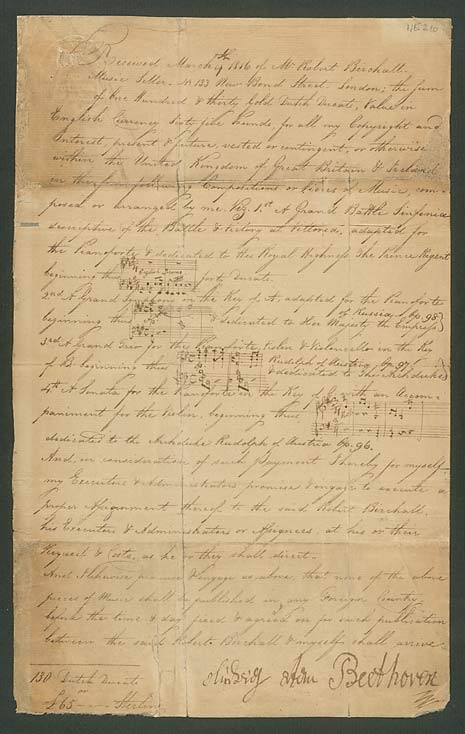

Summary of ownership and receipt for Robert Birchall, March 9th, 1816

With the confirmation of ownership Beethoven's rights for publishing in the UK and Ireland

of the mentioned compositions were ceded to the publisher and obliged him to delay publication in other countries

until after the pieces had been released in Britain. The compositions are individually listed with incipit,

dedicatee and opus number (the Seventh Symphony wrongly named op. 98). The simultaneous publication on the

Continent and in Britain should protect any publisher from financial damages caused by unauthorised reprints.

Nevertheless, the Vienna publishing house Steiner already published the violin sonata in July 1816 whereas

Birchall published the English edition three months later in October. In case of opus 91 Birchall was ahead of

Steiner by two months. Also the piano arrangement of the Seventh Symphony was first published in Vienna and two

months later in London in January 1817. Obviously, Beethoven never succeeded in giving London exact publication

dates.

Although the composer must have received his remuneration at the latest in early May, he did not send the signed

document to Johann von Häring who took care of his English correspondence to be forwarded to England until

September 1816.

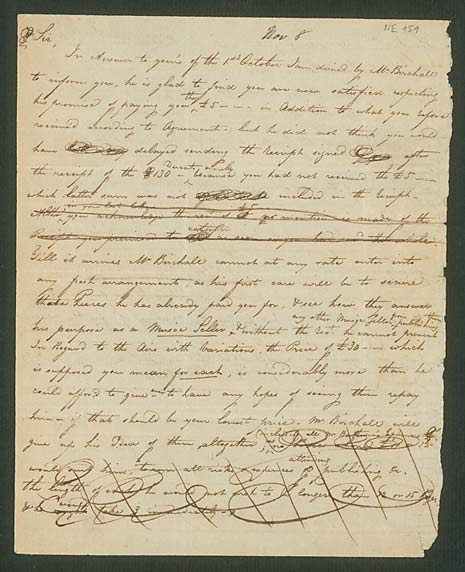

Letter concept from Christopher Lonsdale to Beethoven, November 8th, 1816

Birchall's employee Christopher Lonsdale expresses his contentment with the payment now being complete. Before,

he had asked Beethoven to indicate one remuneration sum including all expenses. Lonsdale repeatedly reminded the

composer of the ownership confirmation and assumed Beethoven would not sign the document until he received

his additional claim. According to the receipt Beethoven had been reimbursed on August 3rd. On September 9th he

had also given Peter Joseph Simrock who visited him in Baden the property confirmation along with a short letter

addressed to Johann von Häring to be forwarded to London. Obviously the further delay was the fault of the

banks. Birchall had continued to commission Beethoven for arrangements of folk songs for violin or cello

accompaniment. However, he considered the remuneration of 30 Pounds requested by Beethoven as excessive. With

a reference to Birchall's bad health other offers (the Piano Sonata, op. 101 and a never completed Piano Trio in F

Major) were refused. The cooperation stopped. As late as December 1816 Birchall published the English original

edition of the trio. Hence, the Vienna first edition was again ahead by three months.

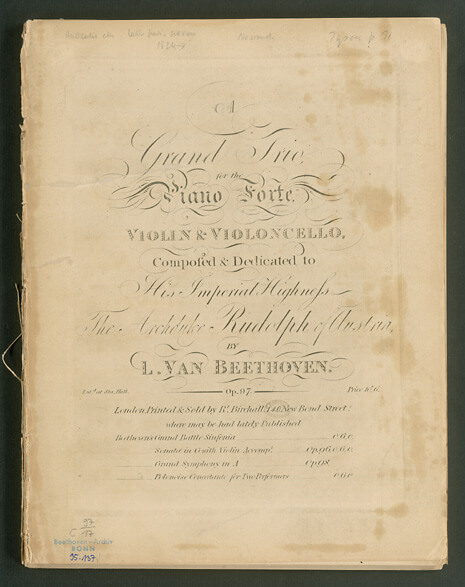

Trio for piano, violin, violoncello (B flat Major) op. 97

Ferdinand Ries also intended to offer the variations on a march by Anton Diabelli (C Major) op. 120 for publication in

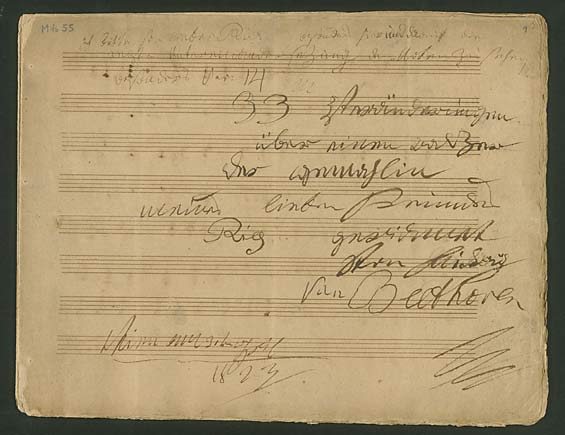

England. On April 25th, 1823 Beethoven made the following announcement: "In a few weeks you will also receive 33

new variations on a subject (Waltz opus 120), dedicated to your wife." The corrected copy is the promised

manuscript. Beethoven himself wrote a dedication and the date on the title: "33 Variations on a Waltz dedicated

to the wife of my dear friend Ries by Ludwig van Beethoven, Vienna, April 30th 1823". The English edition was

never published as Ries tells in his Beethoven memoires: "Because Beethoven had delayed the sending so long and

had forgotten all about the commission, that when I brought Boosey [the London publishing house interested in

publishing the composition] the variations, we found out it had already been published in Vienna with a

dedication to Madam Brentano."

Title page written by Beethoven of the corrected copy of the Diabelli Variations op.

120

Publisher Robert Birchall

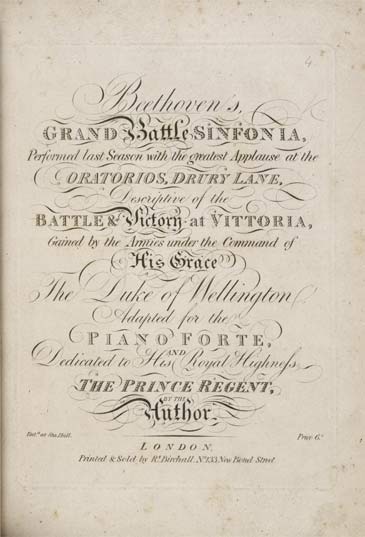

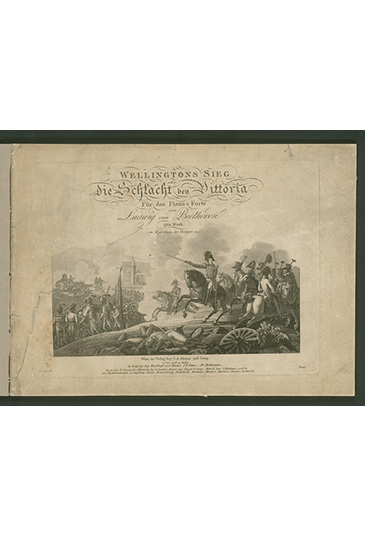

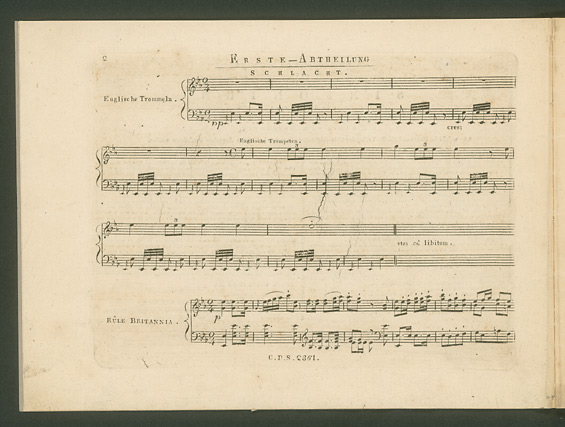

The "Grand Battle Symphony", op. 91

In June 1813 the troops of Sir Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, defeated Napoleon at the Vitoria plain in

northern Spain. Inventor and music mechanic Johann Nepomuk Mälzel (he also built hearing tubes for

Beethoven) convinced the composer of his idea to put the defeat of the French to music. Originally intended for

Mälzel's new musical device, the so-called "Panharmonicon", the composition was too powerful to be transferred

to a mechanical musical machine. Beethoven then arranged the composition for orchestra and added a piece of

battle music (including the marches "Rule Britannia" and "Marlborough") and an intrada. As a composition written for a

special occasion it matched the current taste and met with great success in December 1813. Thereafter, the

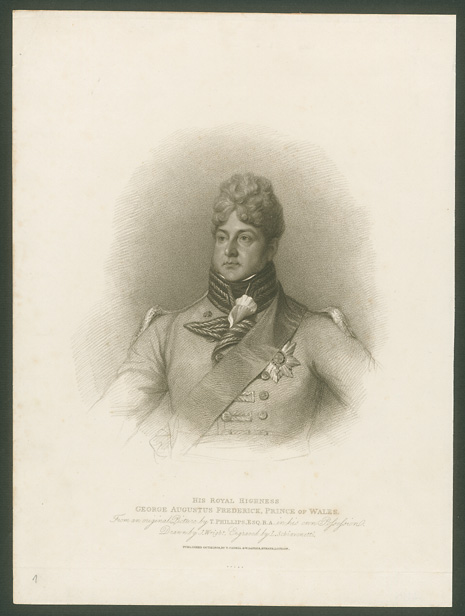

piece was performed many times in Vienna. Beethoven dedicated the composition to the prince-regent, later

King George IV of England who governed the country since 1811 because his father had become insane. Already in

early 1814 had Beethoven sent the score copy to the dedicatee but neither received an answer nor the expected

remuneration. Instead, the composition was performed in London on February 10th, 1815, a première that

would be followed by many successful performances. The topic was reported effusively in the newspapers so that

Beethoven who spoke French but not English, asked Johann von Häring to write to conductor George Smart. Both were

pleased with the great success the battle music had in London. However, Beethoven asked the conductor for advice

because he did not want to publish the piano arrangement without the dedicatee's permission. In addition, he offered

Smart other compositions for English publishers. In the end Beethoven thanked Smart for his efforts dedicated to

his "children" (i. e. his compositions).

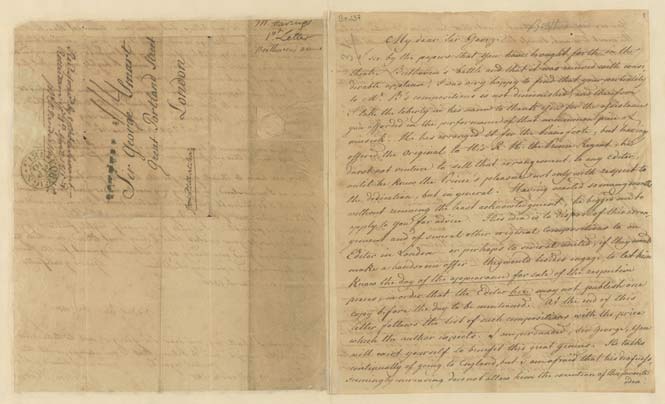

Letter to George Smart in London, March 16th and 19th, 1815

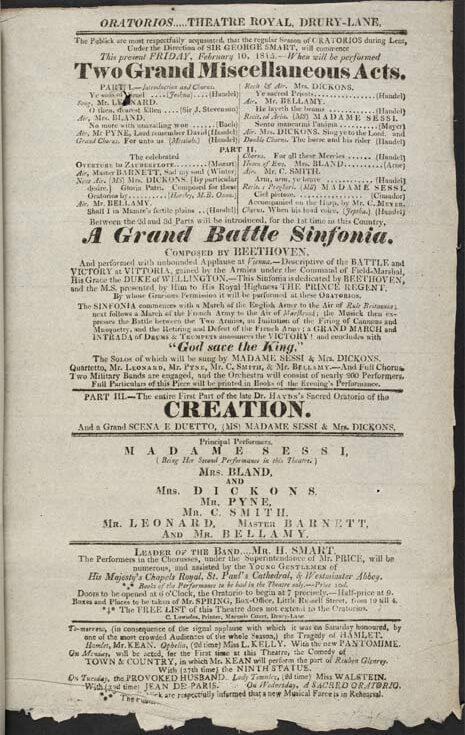

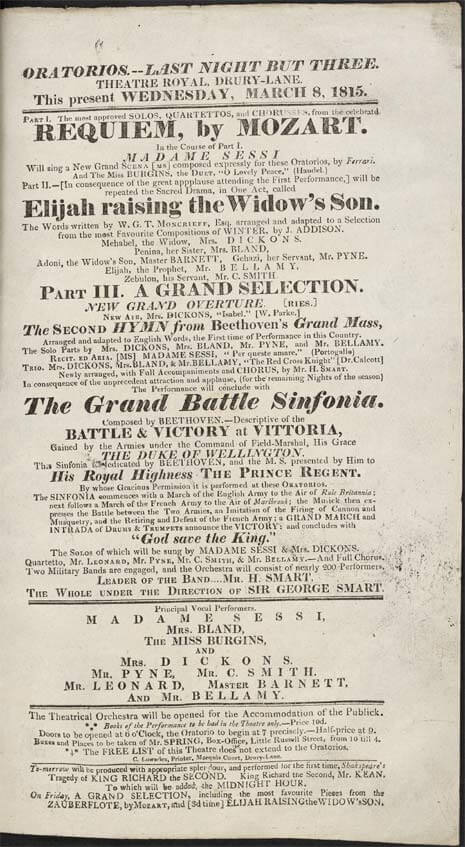

The announcement for the English first performance under Sir George Smart at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane on

February 10th, 1815 explicitly mentioned the great success the composition had in Vienna: "Between the 2nd and

3rd Parts will be introduced, fort he 1st time in our Country, A Grand Battle Sinfonia. Composed by Beethoven.

And performed with unbounded Applause at Vienna." The announcement for the second presentation in London a few

days later bore the following remark about the success of the previous performance: "Which was performed, for

the first time, on Friday last, with universal Acclamations of Applause, and unanimously encored," that means

with continuously growing public acclaim. Until May the piece was performed over and over again while the

euphoria of the audience steadily increased. In the following year the orchestra counted 200 musicians. Until

November 1817, when Princess Charlotte died, the piece was part of almost any concert performed here.

Beethoven's oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, op. 85, was also presented at this theatre for the first

time in England in February 1814 and repeated several times.

Announcements for performances of op. 91 at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane

The British Library

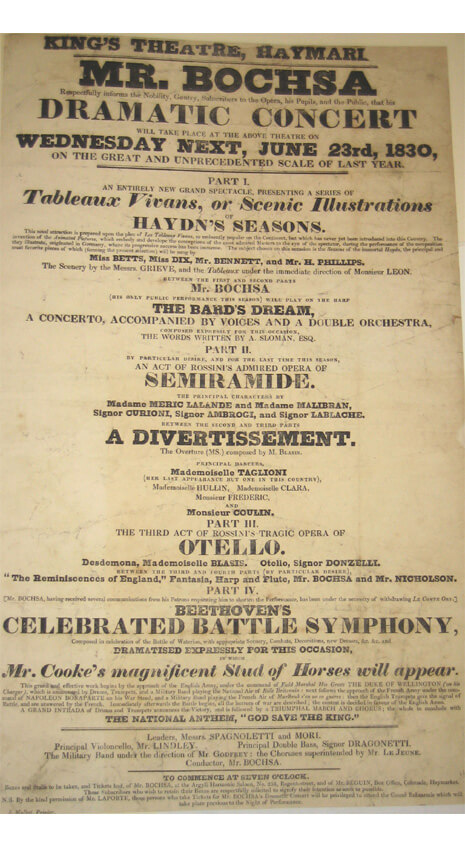

Announcement for the performance at King's Theatre on June 23, 1830

The British Library

The scenic performance on June 23rd, 1830 at The King's Theatre in Haymarket must have been quite noteworthy when

apart from stage setting, costumes and other decorations a troup of horses was seen on stage.

Publisher Robert Birchall

The "Grand Battle Symphony", op. 91

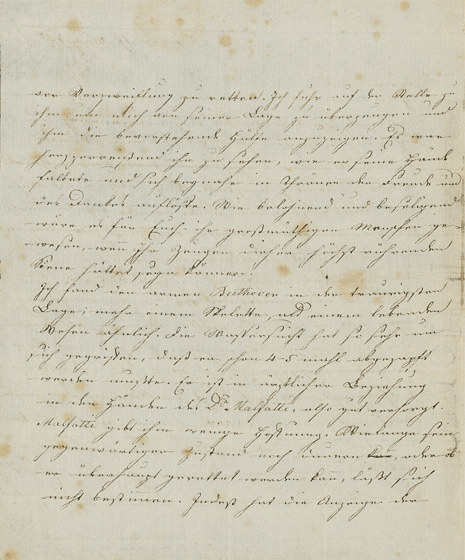

George Augustus Frederick, Prince-Regent and later King of England (1762–1830)

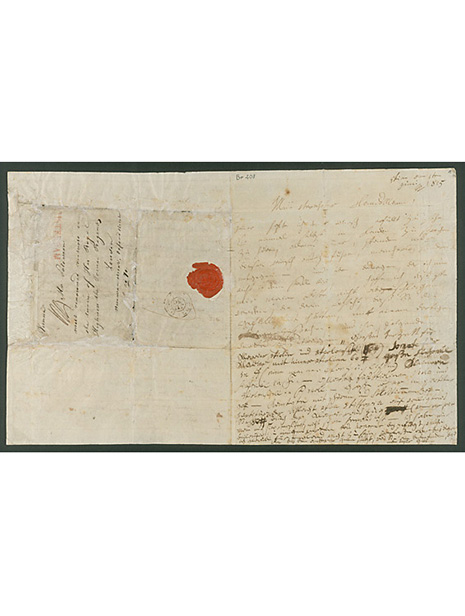

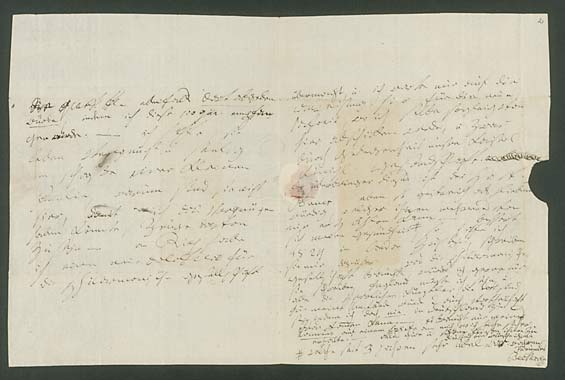

Letter to Johann Peter Salomon in London, June 1st, 1815

The address written by someone else reads: "Vienna / Mr. Salomon / most renowned virtuoso in / the service of His

Royal / Highness the Prince Regent / London / Newman street, Oxford street / no. 70." A few months after the

letter to Smart Beethoven asked Johann Peter Salomon if he saw a chance to have the prince regent at least

reimburse him for the costs for copying the Battle Symphony. Apart from that he had heard a piano reduction was

being prepared which would violate his rights and remuneration as author (in fact this was not the case and

Beethoven had already sold the composition in Austria to Steiner). Although he tried several times to remind

the English king of this neglect, Beethoven never received any acknowledgement for the dedication. After having

sent the king a printed copy of the score many years later, Beethoven once more asked the renowned London harp

manufacturer Johann Andreas Stumpff for help in 1825 but his efforts were also in vain. Stumpff replied: "I have

made many inquiries with even the ones closest to the king in relation to the Battle at Victoria but have heard

no more than one would regret not being able to help in this matter and that Sir Benj. Bloomfield, then director

of the musical department, who might have received the composition, was no more in London but at the Swedish

court as an envoy for many years and that possibly with favourable luck one might remind the king in this

matter."

English original edition of the piano reduction op. 91

German original edition of the piano reduction op. 91

The planned simultaneous edition by Steiner in Vienna and Birchall in London failed in this case, too. Beethoven

had asked the Vienna publisher to delay the edition because he needed to find an English publishing house first.

At the end of November 1815, he told Ries the title of the English edition and asked for the publication date. In

December Ries confirmed receipt of the scores. Beethoven was told that there would be a delay of three to four

months which Beethoven then indicated to Steiner. Nevertheless, the English edition was published within a month

in January 1816 and thus two months earlier than the German edition.

Beethoven's relationship to Great Britain

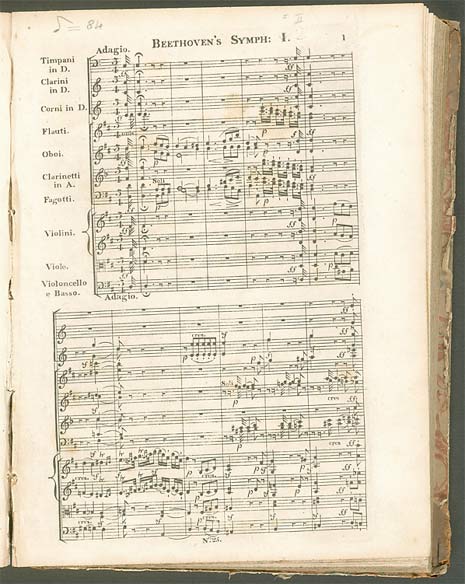

Other publishing houses

Two Italian musicians working in London, Francesco Cianchettini and cello player Sperati, referring to themselves

as "Importers of Classical Music" on the title page, published a series of 27 symphonies in score editions each

month between 1807 and 1809. Apart from 18 symphonies by Joseph Haydn and 6 pieces by Mozart, Beethoven's first

three symphonies were published here as score editions for the first time, a score type that would not be common

on the Continent until the 1820s. The first edition in voices, published in 1804 by a Vienna publisher, served

as master. Probably, Beethoven did not know anything about this edition and did not receive any remuneration.

Neither was it Beethoven who dedicated the composition to prince regent George of England but the

publishers.

First score edition of the Second Symphony, op. 36, Cianchettini & Sperati, London

1808

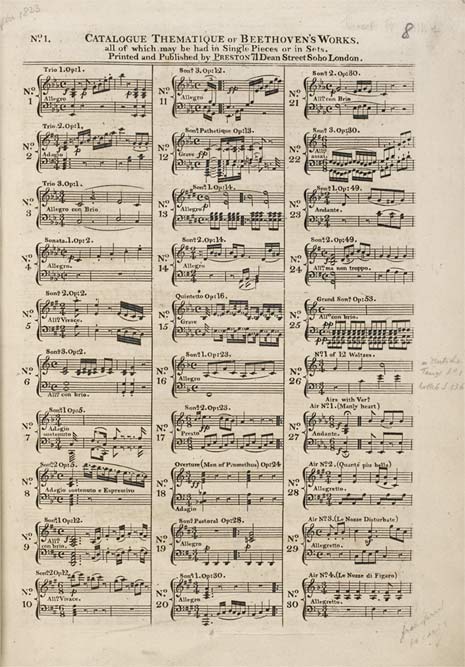

The displayed catalogue excerpt shows that the London music publishing house Preston also edited a number of

reprints besides the folk song arrangements published by George Thomson.

Catalogue of the Beethoven compositions published by Preston, 1823

The British Library

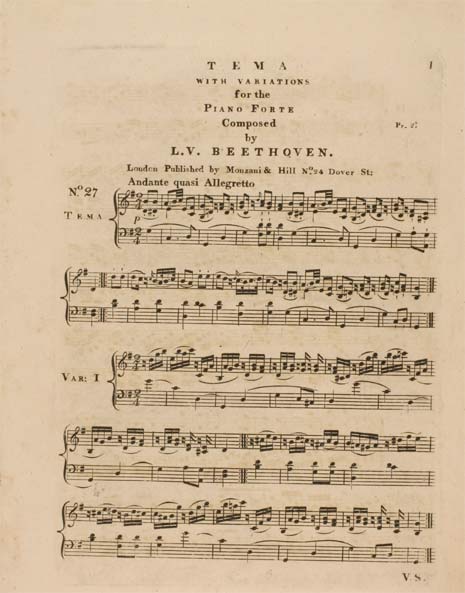

Between 1808 and 1820 the London publisher Monzani & Hill edited a monumental full edition of Beethoven's piano

and piano chamber music compositions - enough sheet music to fill 75 volumes. All publications were reprints. Of

booklet 27 only one single copy remains, kept at the Beethoven-Haus for a few years. It contains the variations

in G Major WoO 77 that were first published by a Vienna publisher in 1800.

Six easy variations for piano on a proper subject (G Major) WoO 77, Monzani & Hill,

London approx. 1813

Beethoven's relationship to Britain

Piano manufacturer Thomas Broadwood

Piano forte by Thomas Broadwood, 1817

Thomas Broadwood, the most productive piano manufacturer of that time in London, gave Beethoven a piano forte in

1817. For this purpose he had invited five of the most important London musicians to his shop to choose a

suitable instrument for the cherished master. Above the company label on the front edge of the pin block the

following text can be read: "Hoc Instrumentum est Thomae Broadwood (Londrini) donum propter ingenium

illustrissime Beethoven." [This instrument is a proper gift from Thomas Broadwood of London to the great

Beethoven.] Next to it Friedrich Kalbrenner, Ferdinand Ries, Johann Baptist Cramer, Jacques-Godefroi Ferrari and

Charles Knyvett signed the instrument. Many years later the Vienna music publisher Carl Anton Spina gave the

piano to Franz Liszt who then dedicated it to the Hungarian National Museum. The displayed instrument,

constructed in the same way, is owned by the Beethoven-Haus.

Letter to Count Moritz von Lichnowsky, early February 1818

Broadwood notified Beethoven in early January 1818 that the instrument had been dispatched on December 27th.

Beethoven immediately contacted Count Moritz Lichnowsky and asked him to speak with the finance minister on his

behalf so that he would be allowed to obtain the instrument free of custom fees and other charges. As can be

seen from the article published in the Vienna newspaper on June 8th Beethoven's wish was granted: "Mister Ludwig

van Beethoven, cherished not only in Austria but also abroad for his great musical genius, received a rare and

precious piano forte from a London admirer as a gift, delivered to Vienna free of charge. With particular

generosity the court chamber of the dual monarchy dispensed with custom fees that are usually applied to foreign

musical instruments, and hence proved in a way pleasant for the arts that one strives to encourage such seldom

merits of genius by humane appreciation."

Beethoven thanked the authorities effusively for the "honourable gift": "I will regard it as an altar on which I

will offer to god Apollo my most beautiful sacrifices of spirit."

The Philharmonic Society

The Ninth Symphony

The Philharmonic Society, founded in London in 1813, became Beethoven's most important institutional partner in

England. The mission of the society, mostly based on private initiative, was to hold concerts at the highest

professional level. Many people of importance to Beethoven held relevant positions: the often mentioned

musicians Sir George Smart and Ferdinand Ries belonged to the group of directors, as

well as composer Neate also a pianist an cellist, was one of the founding fathers. The first concerts each had a composition of Beethoven

as the core. In most cases this was a symphony or other composition such as the popular Septet op. 20 or the

Quintet op. 29. The mixed concert programme typical of that time also featured compositions by Cherubini,

Mozart, Haydn and Boccherini. In 1815 the Philharmonic Society bought three pieces from the work series

Beethoven had offered to Smart and Salomon for publication in England: the overtures for "The ruins of Athens"

("Die Ruinen von Athen"), op. 113 and "King Stephan" ("König Stephan"), op. 117 and the "Name Day Overture" ("Zur

Namensfeier"), op. 115. In the same year Neate stayed in Vienna where he visited Beethoven. When he left for

London in February 1816, he took several compositions to present in the concerts of the Philharmonic Society

and/or offer them to London publishers. Beethoven also hoped for a beneficiary concert to his avail.

Unfortunately, he was disappointed and felt betrayed after he had not heard anything from Neate for months but

had read about a successful performance of his symphony in London in the press. It cannot be said for sure if

the symphony presented was indeed the new Seventh Symphony or the often performed Fifth Symphony.

In the following year the Philharmonic Society invited Beethoven to London. "We would like to have you

with us here in London next winter," wrote Ferdinand Ries on June 9th, 1817. The flattering introduction reads

as follows: "The Philharmonic Society where your compositions are preferred to any other wishes to give you

proof of its admiration and gratitude for the many wonderful moments we were able to enjoy thanks to your

exceptional compositions of genius." The society was willing to pay Beethoven 300 guineas for a season-long stay

in London and for the compositions of two symphonies that should then be the property of the Society. During his

stay he would be able to give other concerts on his own which would be a nice source of additional income.

Beethoven requested an additional minimum remuneration of 100 guineas to cover his travel costs, since they might be

higher because of a necessary travel companion. The Society refused his request and the journey never took

place, certainly also due to Beethoven's bad state of health and the concerns for his nephew.

Still, Beethoven intended to visit England and told Ries in 1822 in a letter: "I am still playing with

the thought to come to London, if only my health permitting; possibly next spring?" On this occasion he also

asked Ries the following: "What remuneration would the Harmonic Society give me for a great symphony?" Ries

forwarded the composer's inquiry and in the first session of the season in 1823 the directors decided in favour

of Beethoven:

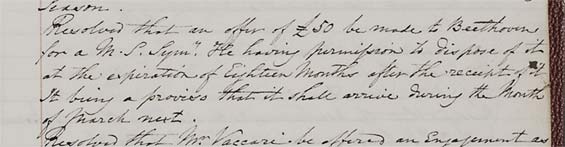

"10. November 1822

Resolved that an offer of £ 50 be made to Beethoven for a M[anu].S[cript].Sym[phony]. He having

permission to dispose of it at the expiration of Eighteen Months after the receipt of it. It being a proviso

that it shall arrive during the Month of March next."

According to the minutes a remuneration of £ 50 was offered to Beethoven for a new and yet unprinted

symphony, given that the manuscript would be received in the month of March. Beethoven would then (as opposed to

the offer of 1817) have the full rights of the composition after 18 months. Ries informed Beethoven of the

decision five days later.

Minute book of the board of the Philharmonic Society, 1822 to 1837, entry from

November 10th, 1822

The British Library

In early 1823 the Philharmonic Society also bought the overture "Consecration of the House" ("Die Weihe des

Hauses"), op. 124 for £ 25. A copy was delivered by the London envoy secretary Caspar Bauer. In the end of

February he notified Neate to send the symphony the same way as soon as he would receive the remuneration. At

that time op. 125 had only been sketched and partially composed. Apart from that Beethoven expressed his hope to

be able to visit London next year when he felt better: "England I would like to see and all the wonderful

artists there. For me it would be of favourable as I can never achieve anything in Germany."

Letter to Charles Neate dated February 25th, 1823

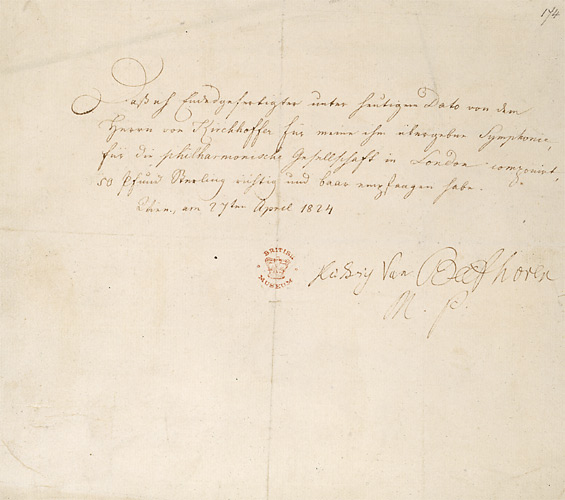

The completion of the symphony was delayed. In several letters from 1823 to Ries Beethoven over and over again

gave new excuses. In the beginning of September he promised messenger Franz Christian Kirchhoffer, employee at

the Vienna bank Hofmann & Goldstein, to deliver the manuscript within the next two weeks. As can be seen from

the receipt, Kirchhoffer had to wait for almost another eight months.

Receipt signed by Beethoven, April 27th, 1824

The British Library

Neate confirmed receipt of the score eight months later on December 20th, 1824. The copy corrected by Beethoven

bears the following title written by the composer: "Great symphony written for the Philharmonic Society in

London.- by Ludwig van Beethoven First movement". The final part shows the handwritten German original text. An

English and (incomplete, partially free) Italian translation was added in London. Schiller's "Ode to Joy" was

performed in this language, particularly suitable for singing.

Copyist´s score of the Ninth Symphony corrected by the composer, 1824

The British Library

The Philharmonic Society

The Ninth Symphony

Charles Neate invited Beethoven to London once more for the season of 1825 to conduct the first London performance of

the Ninth Symphony. For a remuneration of 300 guineas he should bring two new compositions, another symphony and

a concert to first performance. Apart from that he would be able to give a concert for his own benefit.

Obviously, the scope of Beethoven's impaired hearing was unknown in London. Beethoven asked for the remuneration

to be increased by 100 guineas, a request that was refused. However, Neate was sure that Beethoven would be

completely content with his stay in England. Like before Beethoven did not undertake the journey. With the

letter the composer enclosed a list of mistakes concerning the Ninth Symphony drawn up by a copyist but pointed

out that these mistakes were found in other copies and might not necessarily show up in the London copy, too.

Later, Neate said that the London copy was flawless.

List of mistakes for the Ninth Symphony, January 27th, 1825

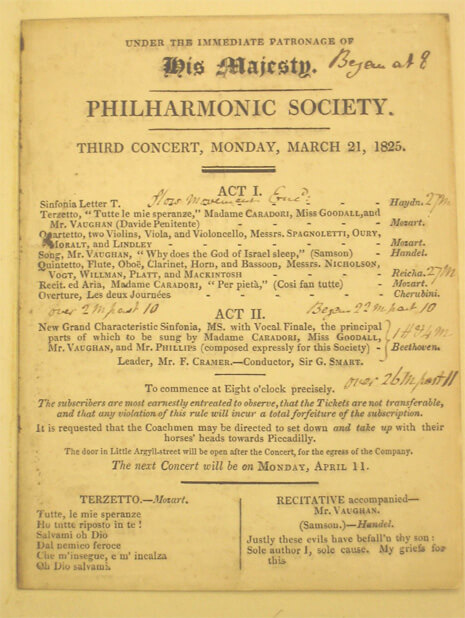

At the first attempt the Philharmonic Society did not manage to perform the composition in a way that met its

requirements. The extremely popular double-bass player Domenico Dragonetti was scheduled for the bass

recitatives as a solo player for which he requested additional remuneration. The Society refused this. In a

letter to the secretary he wrote that he would even have requested double had he known the score before. A

public rehearsal on February 1st became a musical and then a press catastrophe and significantly

influenced the review of the regular performance on March 21st, 1825. For the critics the piece was too long and

too difficult. Sir George Smart, a conscientious conductor and artist, had explicitly asked the directors of the

Philharmonic Society to delay the presentation until it was clear whether Beethoven was coming to London to "partake in the

performance" (as it was wisely described during the Vienna first performance) despite his hearing impairment

that might be underestimated in London and until questions had been answered such as the right time for the bass

recitatives in the fourth movement. Urged by Beethoven's Vienna friends and contrary to the agreement with the

Philharmonic Society the symphony had already been presented for the first time almost a year earlier in Vienna

on May 7th, 1824, and had been met with great success. As late as ten years after the English first performance

the composition achieved success in London. The Academy presented the choral finale separately at the Hanover

Square Rooms, this time with an English translation by conductor Charles Lucas. Now the audience understood the

meaning. Another two years later the Philharmonic Society also managed to hold a successful presentation under

Ignaz Moscheles that then led to the suggestion to perform the composition every year with a choir of 1,000

members and an orchestra of 500 musicians as apotheosis and great European freemason anthem. In 1927 the

suggestion was carried out, even if in a different way. The Strasbourg Council of Ministers of the European

Community chose a part of the choral finale in a plain instrumental version as European anthem.

Programme of the English first performance of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony on March

21st, 1825 with handwritten notes by George Smart

The British Library

Half a year after the presentation Sir George Smart travelled to Vienna and met Beethoven several times in Vienna

and Baden.

Sir George Thomas Smart (1776–1876)

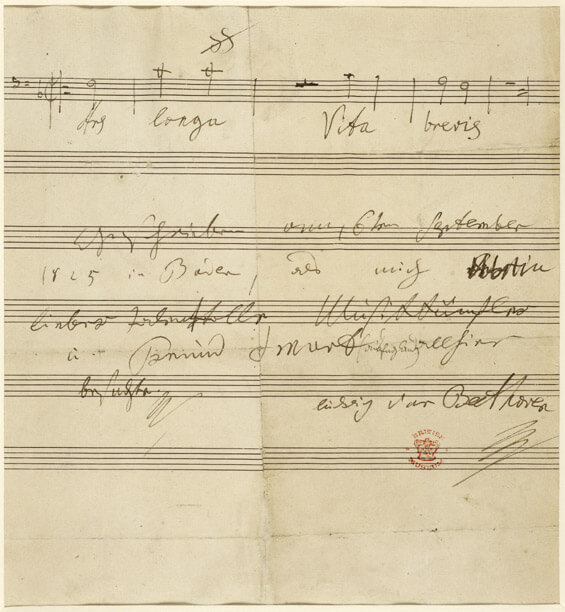

On the occasion of a final visit on September 16th Smart gave the admired composer a diamond pin. In gratitude

Beethoven composed the canon "Ars longa, vita brevis," ("Art is long, life is short"), WoO 192. Smart later noted in his diary "as quickly as his

feather pen was willing to write, within about two minutes". The dedication written by Beethoven reads:

"Geschrieben am 16ten September 1825 in Baden, als mich mein lieber talentvoller Musikkünstler u. Freund Smart

(aus England) allhier besuchte. Ludwig van Beethoven." ("Written in Baden on September 16th, 1825 when my dear

and talented music artist and friend Smart (from England) visited me here. Ludwig van Beethoven").

Canon "Ars longa, vita brevis"

The British Library

The Philharmonic Society

The money gift

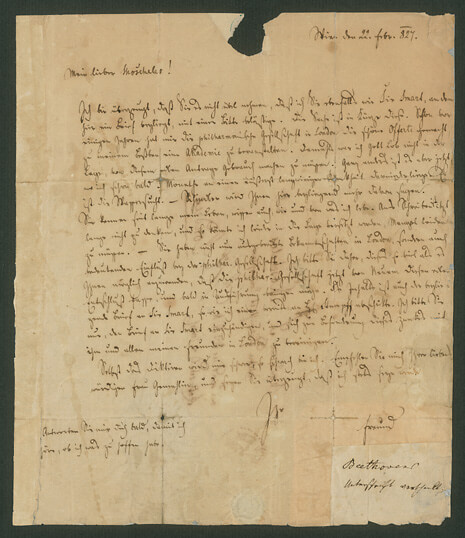

In February 1827, Beethoven, already fatally ill, contacted his old acquaintance Ignaz Moscheles to ask for

financial help. George Smart and Johann Andreas Stumpff received similar letters. In earlier years the

Philharmonic Society had been in correspondence with Beethoven several times concerning a concert for his own

avail. Now Beethoven, who had already been unable to work for months, felt himself in the situation to ask for

such a concert. As weak as he was, he had to dictate the letter. Only the signature later cut out by Moscheles

was written by his hand.

Letter to Ignaz Moscheles dated February 22nd, 1827

Originally from Prague, pianist, composer and conductor Ignaz Moscheles, came to Vienna in 1808. Until 1820

he was part of Beethoven's circle of acquaintances. From the early 1820s until 1846 Moscheles lived in London but

remained in written contact with Beethoven until his death.

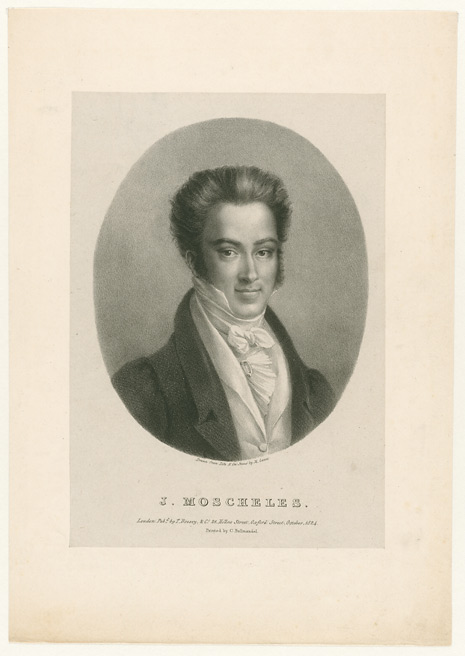

Ignaz Moscheles (1794–1870)

Thuringian harp manufacturer Johann Andreas Stumpff was a fervent admirer of Beethoven. In the autumn of 1824 he

had visited Beethoven in Baden and remembered the visit in a preserved draft for a letter: "Still my loving

heart is grateful for the fortuity that led me to lovely Baden and see face to face the most favourite of the

muses and creator of the most eminent melodies ever imagin by the human spirit and who so kindly received me

with such generosity that I will strive to earn all my life long." In the following year he particularly pleased

the "greatest living musician Luis v. Beethoven" with the gift of a 42-volume full edition of the works by Georg

Friedrich Händel.

After Beethoven's letter for help arrived in London the board of the Philharmonic Society immediately held a

session and granted the composer's wish. The generous sum of £ 100 was quickly sent to Vienna. It was a noble

deed by the Society for which Beethoven had not always been a reliable partner but still a highly appreciated

artist. The day Beethoven was buried, which he, of course, did not know yet, Moscheles revealed to the Society

the content of the letter his friend Sebastian Rau had written him. In the letter Rau described the tremendous

joy Beethoven had expressed when he brought him the money gift the Society had sent. In fact, it was Beethoven's

last great feeling of joy and it also improved the state of his health for a short time.

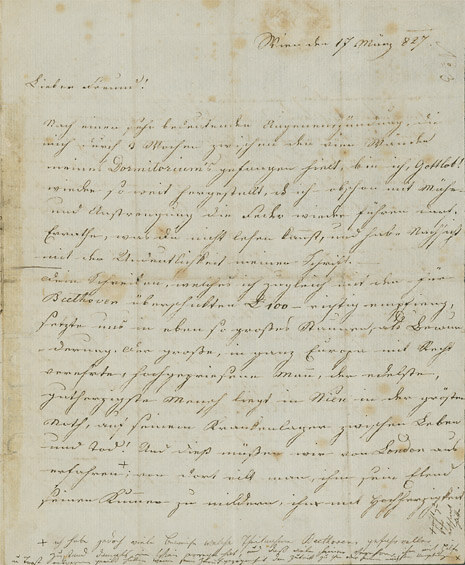

Sebastian Rau to Ignaz Moscheles, March 17th, 1827

On March 28th Sebastian Rau informed London of Beethoven's death. To Moscheles he wrote: "Beethoven is gone, he

died on March 26th in the evening between 5 and 6 o'clock, bitterly struggling with death and in terrible

suffering. But he had lost consciousness the day before." Vienna piano manufacturer Johann Baptist Streicher

sent a letter with the same date and similar content to Johann Andreas Stumpff. In 1822 Streicher had undertaken

a long study journey and had become friends with Stumpff in London.

Beethoven on his deathbed, March 1827, drawing by Teltscher (1801–1837)

Josef Teltscher obviously visited Beethoven several times in March 1827 to draw him. According to the reports of

Anselm Hüttenbrenner and Johann Baptist Jenger it is quite certain that he was also present in Beethoven's

living room in the afternoon of March 26th when the composer died. From the way Beethoven is drawn it can be

assumed that he was still alive, yet unconscious, when Teltscher drew him.

Epilogue

Aftereffects on the Island and Continent

Joseph Joachim (1831–1907)

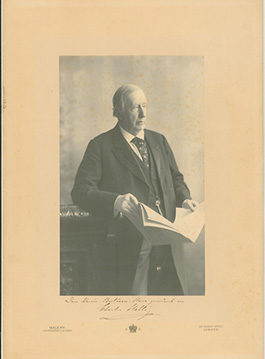

Charles Hallé (1819–1895)

As a young man, Joseph Joachim began his musical studies in Vienna with Joseph Böhm (1795–1876), who

had known Ludwig van Beethoven in person and participated, among others, in the first performance of the

Ninth Symphony.This, through his teacher Joachim had a link to the authentic interpretation of the compositions

by his admired composer. In 1844, at an age of only 13 years, he made his first public appearance as a solo

player in the Violin Concerto of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. His performance was widely acclaimed. Ever after

he was regarded as THE interpreter of this composition for which he also composed two cadenzas of his own. Later

Joachim became the grey eminence of the German musical life and was, amongst others, honorary president of the

Beethoven-Haus. In this position he initiated the Bonn chamber music festival tradition. It was him and his

quartet who made Beethoven's late string quartets known to the general public by interpretations his

contemporaries considered unrivalled.

Karl Halle, born in Halle/Westphalia, was quite an influential figure for English musical life of the 19th

century. He settled in London early and presented Beethoven's piano sonatas first in concerts held at home, then

in public concerts. In Manchester he later founded an orchestra named after him that became known for exemplary

performances.

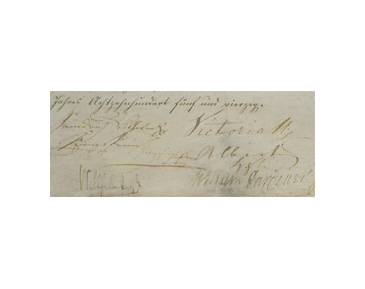

Signature of Queen Victoria of England on the deed of foundation of the Bonn

Beethoven monument, 1845

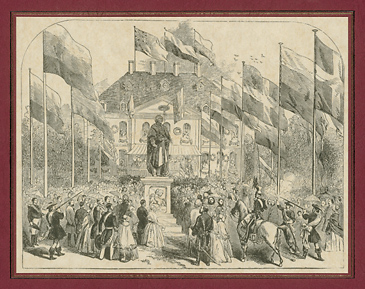

Unveiling of the Beethoven monument by Ernst Julius Hähnel at the Münsterplatz in

Bonn

Before the Beethoven monument at the Münsterplatz in Bonn was officially unveiled in a ceremony on August 12th,

1845 the honorary guests, among them Queen Victoria of England, her prince consort Albert, King Friedrich

Wilhelm IV of Prussia and Franz Liszt, signed the deed of foundation. The members of the committee also signed

the document. Two originals of the document were drawn up, and having been signed,

each original was enclosed in a leaden capsule and enclosed at the foot of the monument. However, no such

capsule with certificate was found when the monument's base was opened in the 1970s during construction works

for the parking garage under the Münsterplatz and the documents were brought to the city archive for

safekeeping.

When the Queen visited Germany the Illustrated London News published an article with pictures of the most

important sights, among them the Bonn Beethoven monument, a map of the river Rhine and genre scenes of the

journey. The same newspaper also published the original of the displayed wood engraving for the first time. The

reproduction is the cover page of a dinner menu card German Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker held in

honour of Queen Elizabeth II on July 3rd, 1986 at the Brühl Castle.

Legal notice

Publisher

Beethoven-Haus Bonn

Bonngasse 24-26

D-53111 Bonn

Germany

Texts:

Dr. Nicole Kämpken

Dr. Michael Ladenburger

This temporary exhibition was shown 22.08.2007 to 18.11.2007 in the Beethoven-Haus.

English translation: deepl, revised by Dr. Paul Ellison