The collector

Family and studies

Hans Conrad Ferdinand Bodmer was born on 16 December 1891 into one of Zurich's most distinguished and wealthy families. The family had lived in the city on the Limmat since the middle of the 16th century and had acquired considerable wealth and influential offices as craftsmen, merchants and factory owners. Culture was very important to the family. The five children of Hans Conrad and Mathilde Bodmer, née Zoelly, met important personalities such as Gerhart Hauptmann, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Thomas Mann in their family home. The third first name is borrowed from Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, who also took over the godparenthood. Hans Conrad and his brother Martin, who was eight years younger, were two of the most important private collectors of the 20th century to emerge from the family. Martin Bodmer dedicated his entire life to the comprehensive task of compiling a 'library of world literature' (Bibliotheca Bodmeriana). Hans Conrad Bodmer, on the other hand, focussed entirely on Ludwig van Beethoven. At a young age, he heard the 'Coriolan' overture op. 62 and a symphony at a concert; since then, Beethoven has never ceased to fascinate him. He also felt a special connection with the composer due to his date of birth - he liked to share the assumption that Beethoven was born on 16 December, as he was.

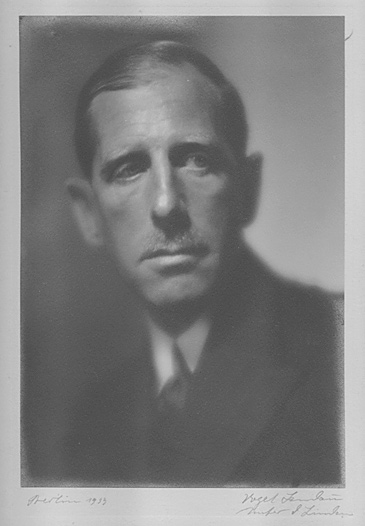

Hans Conrad Bodmer, Berlin 1933, photo: private collection, Bonn

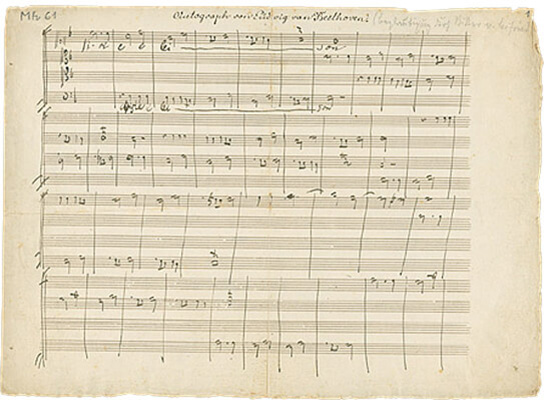

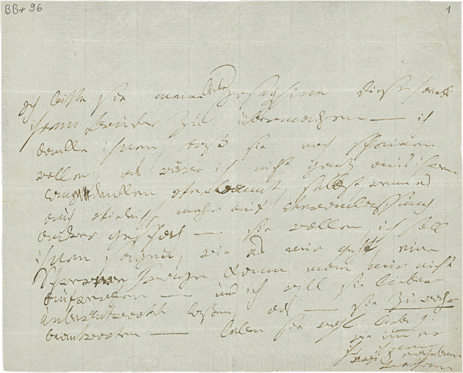

Bodmer himself played the violin and sang in the choir. He received his first introduction to music theory from Volkmar Andreae, chief conductor of the Tonhalle Orchestra for many years. After leaving school, he studied musicology with Max Friedländer and Hermann Kretzschmar in Berlin between 1913 and 1916 and took private composition lessons with Emil Nikolaus von Reznicek. However, only a few of his compositions have survived, including two songs based on poems by Ludwig Uhland and Eduard Mörike and several fugues for mixed choir and organ or for piano. A Kyrie double fugue is particularly interesting in connection with Beethoven. It is based on the theme of a double fugue in F major for four-part mixed choir, which Beethoven composed in 1794/1795 during his own lessons with Johann Georg Albrechtsberger. Beethoven's manuscript was offered for sale by Karl Ernst Henrici in Berlin in 1916 and could have been one of Bodmer's first acquisitions.

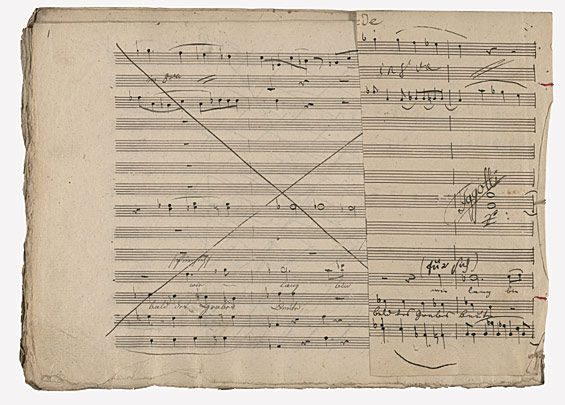

Ludwig van Beethoven, draft of a double fugue for four-part mixed choir

Hans Conrad Bodmer, Double fugue on the same theme. Private collection, Bonn

Like his other fugues, Bodmer's composition contains correction notes by his teacher Reznicek. In an analysis of his own Kyrie double fugue, he noted: 'A sketch leaf of Beethoven's that came to my attention contained this 6-bar double theme with text. [...] It was a marvellous feeling for me to work on this unused Beeth. theme'

Bodmer remained close to his teacher even after his time in Berlin. Reznicek dedicated his Symphony in the Old Style to him in 1918. In 1920, Bodmer travelled to Darmstadt for the premiere of Reznicek's opera 'Ritter Blaubart' and later also arranged for a production of the opera at Zurich's Stadttheater by financing the entire performance, including costumes and decorations.

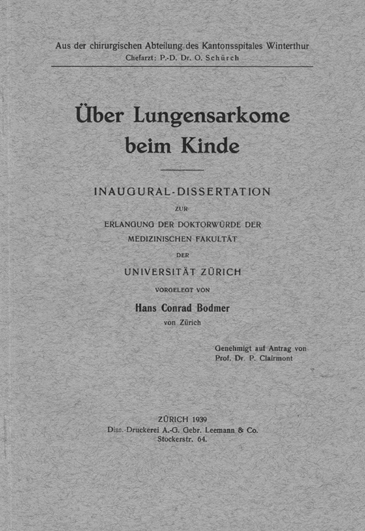

Later, Bodmer completely renounced his own artistic activity. Instead, he turned in a completely different direction: in February 1928, the 36-year-old began studying medicine at the university in his home town. Bodmer completed his clinical semesters with Otto Mauritz Schürch, five years his junior, who married his daughter Charlotte in October 1935. After 10 years - Bodmer had to interrupt his studies for over a year due to pneumonia - he graduated with his state examination and doctorate. His dissertation 'On pulmonary sarcomas in children' was published in 1939. However, Bodmer never practised as a doctor.

Bodmer's dissertation from 1939. Private collection, Bonn

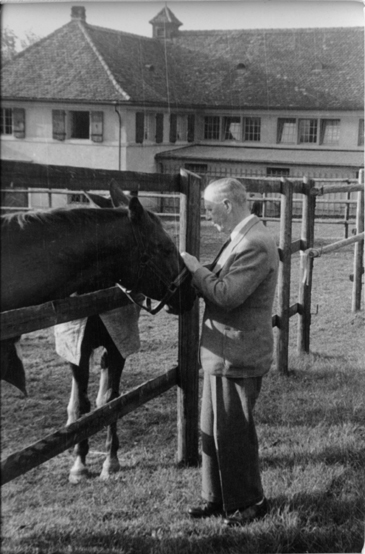

In addition to his generosity - he built the estate in Montagnola for Hermann Hesse and granted him the right to live there for life - and his enthusiasm, his strong love of nature was another key character trait. He loved the tranquillity and majesty of the mountains, which he enjoyed as a mountaineer on extensive tours. He had a strong passion for horses; he ran his own riding stables in Rüschlikon and Munich-Riem. But he also had pets such as dogs, cats and even a goldfish called 'Sir Henry Fish'.

Bodmer with his horses in his riding stable in Munich-Riem, photo: private collection, Bonn

Bodmer married Elsa Stünzi in 1916, during his last year as a student in Berlin. He had met his future wife at a concert where she happened to be sitting next to him. Hans Conrad and Elsa Bodmer had three children: the aforementioned Charlotte, Hans Conrad and Peter.

Elsa Bodmer with her dog, around 1950, Photo: private collection, Bonn

The collector

Structure of the collection

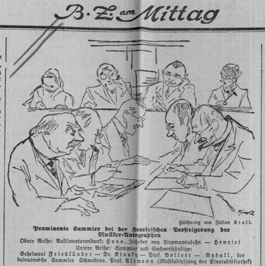

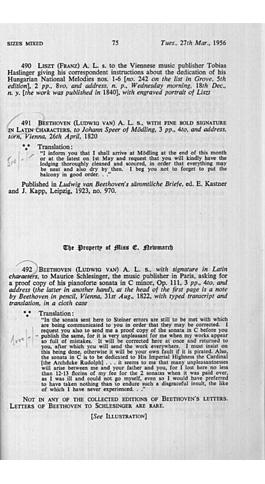

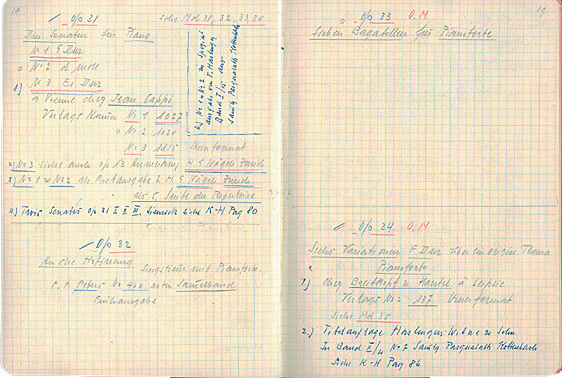

Bodmer's father died in January 1916. He left his widow and children a considerable fortune. With this excellent financial security, H.C. Bodmer (as his father had already done, he reduced his first names to his initials after his father's death) was able to start building up his Beethoven collection without any worries. The basis was a small stock of Beethoveniana from old family property, namely the original editions of the Three Violin Sonatas op. 12 and the Three Piano Sonatas op. 31. The time was very favourable for his project, as many Beethoven documents were still in private hands and the great economic crisis of the 1920s and the consequences of both world wars led to a wide supply on the autograph and antiquarian book market. Bodmer acquired the majority of his outstanding pieces at auctions, but never purchased them himself, instead always acting through dealers, as he attached great importance to discretion with regard to his collection. He always set clear limits for his commission agents and was not prepared to buy at any price. He soon cultivated a close relationship with the Zurich antiquarian bookseller August Laube, and Laube took on most of the purchases. He also bid successfully when Ernst Henrici in Berlin auctioned off the autographs of Wilhelm Heyer's disbanded music history museum in Cologne. The outstanding manuscripts of the Piano Sonata in F sharp major op. 78, the trombone parts for the 9th Symphony, the draft of a memorandum to the Court of Appeal, a conversation booklet and several letters were significant additions to Bodmer's collection.

Auction catalogue from Sotheby's

August Laube (far right) at an auction, probably in the 1920s

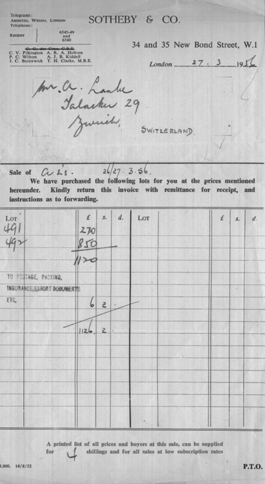

Bodmer acquired another centrepiece of the collection, the 'Waldstein Sonata' op. 53, from the descendants of the dedicatee in 1938. Bodmer was able to expand the collection's focus on Beethoven's letters by acquiring the complete remaining holdings of letters from the publishing archives of Simrock in Bonn (later Berlin), Artaria & Co. in Vienna and Breitkopf und Härtel in Leipzig. In terms of sheer numbers, the Beethoven letters far outweigh all other items. His last ever purchases also fall into this category. From his sickbed, he placed two orders with August Laube for the Sotheby's auction in London on 27 March 1956, with the local guarantor Heinrich Eisemann winning the bid for a letter to Beethoven's landlord Johann Speer in Mödling and a previously unpublished letter to his publisher Maurice Schlesinger.

Auction catalogue from Sotheby's

Invoice from Sotheby's to Laube

For the Beethoven Year 1927, Bodmer planned to publish a private edition of 100 copies. A selection of letters, music autographs, pictures and relics from his collection were to be presented to the public for the first time in three chapters. In this context, detailed inventory lists were compiled, showing the remarkable quality and quantity of the collection, which had only been started 10 years earlier. Unfortunately, the project failed as the author commissioned by Bodmer, Leopold Schmidt, fell seriously ill and died on 30 April this year.

Max Unger was the first recognised Beethoven researcher to be granted unrestricted access to Bodmer's collection. Bodmer appointed him curator of the collection in 1932. In the following years, Unger devoted himself primarily to cataloguing and expanding the Bodmer Collection. He also repeatedly wrote expertises for Bodmer when new pieces were offered. After several essays, a complete, detailed catalogue of the collection was finally published in 1939 in the Corona publications published by Bodmer's brother Martin. The catalogue was published anonymously without mentioning the collector's name or location. Only the title 'A Swiss Beethoven Collection' gave a hint for those already in the know.

The collector

'This small but unique museum'. The house 'Zur Arch'

Bodmer's estate in Zurich's Bärengasse

The Beethoven collection was housed on the first floor of the building on the right. Photo: private collection, Bonn

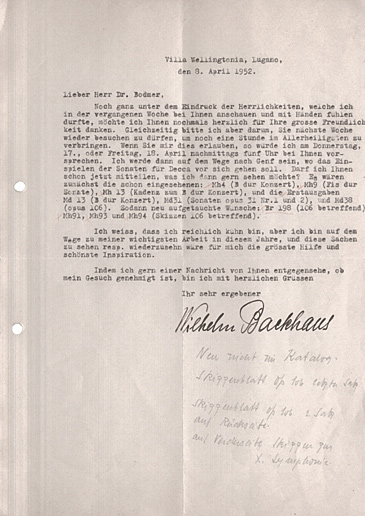

Bodmer had set up three rooms in his cosy old house at Bärengasse 22 for his valuable collection. The so-called 'Arch' had been the family's ancestral home since 1818. Only a few guests got to see the Beethoven collection. At this time, Bodmer still regarded it as his own world, which he only wanted to share with a 'morally authorised' select few. These included the outstanding Beethoven interpreters Wilhelm Backhaus, Alfred Cortot, Walter Gieseking, Wilhelm Furtwängler and Pablo Casals with his trio partners Sándor Végh and Mieczyslaw Horszowski. Certain that Beethoven's original manuscripts and the overall atmosphere of the three rooms would inspire the artists in a special way, Bodmer was happy to grant them access. Only a few researchers enjoyed the privilege of being able to study the manuscripts. Erich Hertzmann, who taught in New York, and the Englishwoman Emily Anderson, who was working on her edition of Beethoven's letters, were given this opportunity. In return, Hertzmann examined for him the autograph parts of Beethoven's last string quartet op. 135, which Bodmer was in the process of acquiring. Anderson described the special aura of the 'Arch' as follows: 'Entering this small but unique museum the visitor immediately feels

that something of Beethoven´s spirit has come to settle there.'

Letter of thanks from Wilhelm Backhaus

The Bodmer Collection first came to the attention of a wider public at the International Music Exhibition in Lucerne in the summer of 1938. Bodmer contributed over 100 exhibits to this major exhibition, so that the Beethoven section was almost exclusively borrowed from his collection. In this context, the mayor of Lucerne wrote to Max Unger: 'Bodmer's incredibly beautiful and rich Beethoven collection in particular should be presented to the Swiss and foreign public as impressively as possible. The most distinguished Swiss collector has fortunately turned his attention to the greatest of the greats and this must be placed at the centre of the exhibition.' Extensive coverage, including in the international press, made the collection a household name even beyond specialist circles.

In June 1949, Bodmer once again took part in an exhibition. At the instigation of his brother, he contributed 18 particularly important pieces from his collection to the 'Exposition des Trésors Musicaux de Suisse' at the Chateau de Nyon near Geneva. The exhibition was curated by Robert Bory, who later wrote a well-known biography of Beethoven.

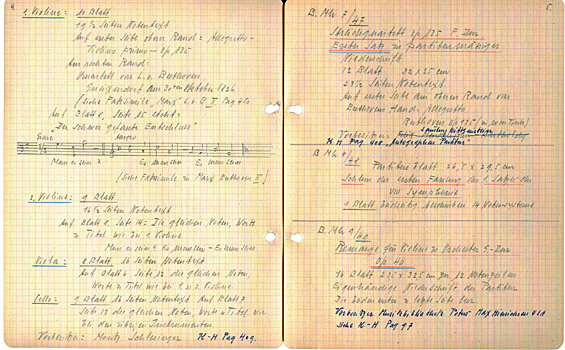

Two pages from Bodmer's own supplementary catalogue

Here is the entry for the two autographs of the String Quartet in F major op. 135

The collector

Bodmer and the Beethoven-Haus I

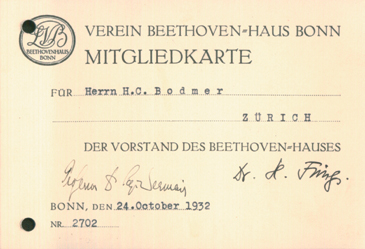

In 1932, Bodmer was offered membership of the Beethoven-Haus Association, which had existed since 1889, which he 'naturally regarded as a great pleasure and honour'. The then chairman of the association and director of the Beethoven-Archiv, Prof. Ludwig Schiedermair, had heard from Max Unger that Bodmer was in possession of a large Beethoven collection and that he would be allowed to catalogue it. However, in the following years, requests from Bonn for reproductions, for example, were initially systematically blocked. August Laube wrote to Bodmer: 'The Beethoven-Museum should please see sense and wait until you release your collection, which is well preserved, for archival purposes.'

Membership card Association Beethoven-Haus Bonn

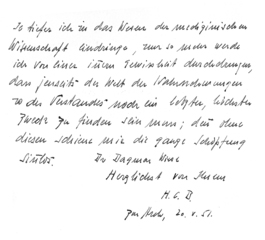

However, this dismissive attitude would later turn into the opposite. After his first visit to the Beethoven-Haus on the occasion of the celebrations to mark the 125th anniversary of the composer's death on 26 March 1952, an intensive, cordial relationship quickly developed between Bodmer and the Beethoven-Haus. The director at the time, Prof. Schmidt-Görg, left the official commemoration ceremony with wreath-laying at the Beethoven monument with his guest early in order to lead him into the birth room to the ringing of the bells. Bodmer thanked him for this strong emotional experience with the following words: 'The marvellous Beethoven celebration, especially the moments I was able to spend with you in Beethoven's birth chamber when the Bonn bells rang, will remain one of my most beautiful memories.' Schmidt-Görg and his young assistant Dr Dagmar Weise succeeded in addressing Bodmer as a like-minded person through personal contact and showing him what they had in common.

Using the example of the Beethoven-Archiv, Bodmer realised how such a collection can be actively handled, how it can be 'harnessed' and, in a sense, 'brought to life'. He came to the realisation that he should make his own collection available to Beethoven research in general and therefore invited Schmidt-Görg and Weise to come to Zurich in May 1952 and film the entire collection. Bodmer paid the costs himself. The opportunity to keep these reproductions available for his own academic work and that of third parties in the Beethoven-Archive was of the utmost importance and was even worth a letter from the Federal President Theodor Heuss. In his reply, Bodmer once again emphasised the uplifting moments of the Bonn memorial service, the 'natural consequence' of which had been 'to have my collection photographed for the Beethoven-Archiv.'

Bodmer also granted the Beethoven-Haus the exclusive right to analyse his collection, which triggered an unparalleled spirit of optimism: the plans for a complete edition of Beethoven's letters were concretised, the complete edition of his works and the sketch edition came within reach.

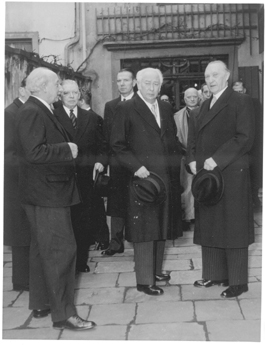

Federal President Theodor Heuss and Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer at the memorial service in the Beethoven-Haus on 26 March 1952

'Swiss page' in the book of guests of honour with entries by Wilhelm Backhaus and H.C. Bodmer dated 26 March 1952 and supplements by Elsy Bodmer, Robert Bory and Minister Max Huber

The collector

Bodmer and the Beethoven-Haus II

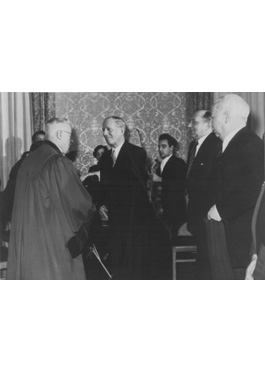

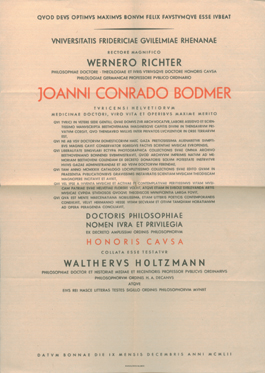

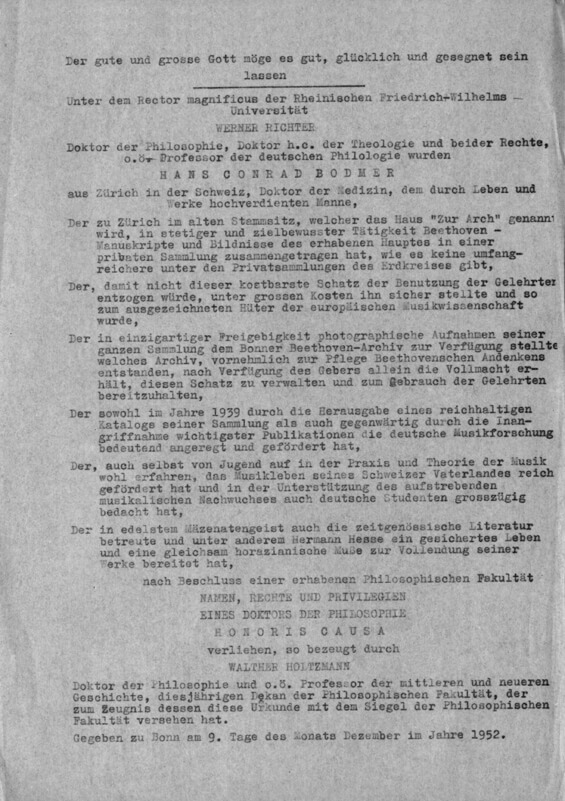

The Beethoven-Haus honoured Bodmer's achievements by awarding him honorary membership on 8 December 1952. The following day, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Faculty of Philosophy at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn 'for his services to German music research and German literature', which made him 'Dr. phil. h.c. H.C. Bodmer'. The President of the Swiss Confederation, who also shared his mutual admiration for Hermann Hesse, attended the award ceremony, as did the Swiss envoy Minister Huber. The ceremony was musically framed by the last two movements of the String Quartet op. 135, of which Bodmer had both parts and score in Beethoven's hand.

Honorary graduation ceremony on 9 December 1952, from left: Dean Prof. Walther Holtzmann, H.C. Bodmer, S. Magnifizenz Prof. Werner Richter, Federal President Theodor Heuss; in the background the Schiffer Quartet with Emil Platen

Honorary doctorate certificate

A few weeks later, Bodmer made a dependent endowment of DM 50,000 to enable the production of facsimile editions of Beethoven manuscripts and the employment of academic staff to analyse the collection. Over the next four years, the sum was more than doubled. The elaborately produced facsimile editions of Beethoven's most extensive document, the draft of a memorandum to the Court of Appeal from 1820, and a centrepiece of the collection, the 'Waldstein Sonata' op. 53, were published during his lifetime, having been agreed with Bodmer down to the last detail of the choice of paper. Soon after his death, the facsimile of the 13 love letters to Josephine Deym was published in 1957, although he had supervised them from his sickbed. Bodmer had a facsimile presented to Theodor Heuss, the Swiss envoy in Cologne, Wilhelm Backhaus, the Beethoven researcher Stefan Ley and his brother Martin.

Thank you card from Martin Bodmer to Prof. Schmidt-Görg dated 25 December 1953

From 15 May to 15 September 1953, the Beethoven-Haus presented the most valuable pieces from Bodmer's collection in a top-class special exhibition. These were cimelia from all areas of the collection. The exhibition, which was again opened in the presence of the Federal President, caused a great stir and was visited by over 50,000 guests.

The collector

Bodmer and the Beethoven-Haus III

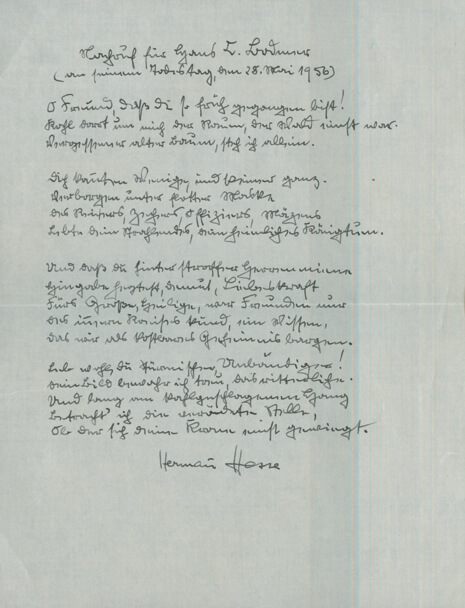

On 28 May 1956, Bodmer died at the age of 65 'after a serious illness endured with the greatest bravery', as the family's obituary stated. On the same day, Schmidt-Görg expressed the Beethoven-Haus' most sincere condolences to his widow: 'It is not only with great sadness that the Beethoven-Haus laments the loss of its honorary member. The Beethoven-Haus owes the generous patron and the tradition-conscious Beethoven connoisseur a wealth of opportunities in the cultivation of Beethoven's legacy. It is impossible to imagine the history of the Beethoven-Haus without his name.' Hermann Hesse wrote an obituary for his great patron. The manuscript was the last item to be added to the Bodmer Collection posthumously.

Obituary of Hermann Hesse

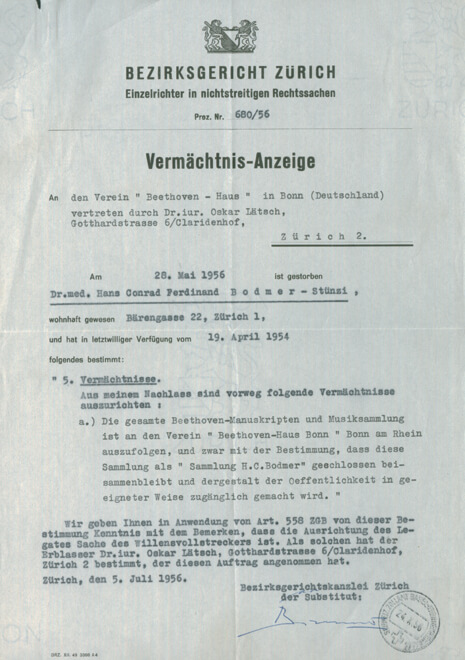

The bequest notice from the District Court of Zurich immediately states under point a.): 'The entire Beethoven manuscripts and music collection is to be handed over to the 'Beethoven-Haus Bonn' association in Bonn on the Rhine, with the stipulation that the collection remains together as the 'H.C. Bodmer Collection' and is thus made accessible to the public in an appropriate manner.' In one of his obituaries for Bodmer, Schmidt-Görg stated that Bodmer had made a corresponding suggestion to him about a year earlier. The collection was then taken over in October 1956, more than tripling the holdings.

On Beethoven's presumed and Bodmer's definitive birthday, 16 December, a memorial service was held in the Beethoven-Haus, at which Federal President Theodor Heuss also gave a short speech. It was here that the legacy was publicly announced.

On 3 November 1957, the permanent presentation of the Bodmer Collection was opened on the ground floor of the Beethoven-Haus in the presence of Elsa Bodmer. Wilhelm Backhaus played the 'Waldstein Sonata' to mark the occasion. Following several remodelling projects and a major restoration of the museum, objects from the Bodmer Collection now permeate the entire permanent exhibition and are also used to a large extent in the special exhibitions.

The collection

Letters

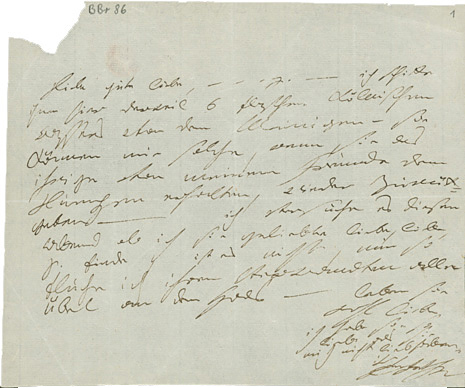

Max Unger organised the Bodmer Collection into various sections, which are described on the following pages. The main collection area was Beethoven's letters. The collection also contains the correspondence with Josephine Countess Deym. Bodmer financed a facsimile of the 13 letters to Josephine. The collection also contains numerous replies and drafts in Josephine's hand. Beethoven had already met Josephine Brunsvik in 1799, when she was not yet married to Count Deym. During a stay in Vienna, she and her sister Therese received piano lessons from Beethoven. After the death of her husband in January 1804, Beethoven comforted the mother of four children with his music and fell deeply in love with the young widow. His first letter dates from November 1804, the 12 others extend over a period of five years until the autumn of 1809. An intimate friendship probably developed between the two, Beethoven's love reaching its peak in the spring of 1805.

Extract from a letter to Josephine Countess Deym, spring 1805

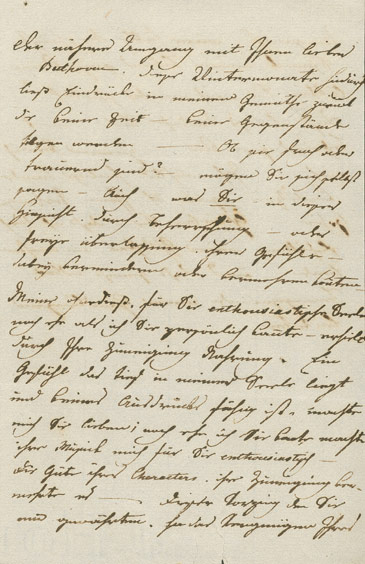

In the winter of 1805/06 Josephine was travelling, in April 1806 she drafted a letter to Beethoven, a further draft from the winter of 1806/07 then very clearly expresses her desire to distance herself.

Draft of a letter from Josephine Countess Deym to Beethoven, winter 1806/07

Josephine tries to resolve her relationship with Beethoven and even allows herself to be denied on several occasions. In the following letter, Beethoven sends her some of his cologne and announces his visit, but is already expecting not to meet her. His great disappointment is reflected in his greeting at the end of the letter: 'I love you as much as you don't love me'.

Letter to Josephine Countess Deym, probably 1807

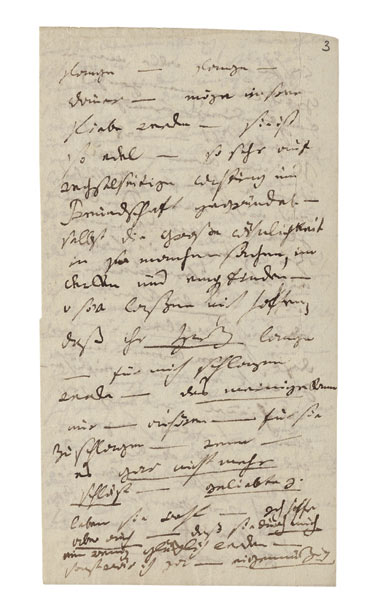

Beethoven's resignation becomes clear in his last letter to Josephine Deym. What had begun with tender love letters ends with a painful farewell.

Letter to Josephine Countess Deym, probably 1809

In 1810, Josephine Countess Deym entered into a second marriage with the tutor of her children, Christoph Freiherr von Stackelberg, from whom she lived largely separately from 1815 until her death in 1821. Beethoven's 'Immortal Beloved', to whom he addressed his great love letter in 1812, has not necessarily been found with the love letters to Josephine Countess Deym. An equally likely candidate is Antonie Brentano.

The collection

Other documents in Beethoven's hand

The memorandum belongs in the category 'Other documents in Beethoven's hand'. At 47 pages, this draft is the most extensive document in Beethoven's hand. Bodmer chose it as the first manuscript to be published in facsimile. In addition to its explosive content, it is also extremely attractive visually, as the emotionally charged writing with numerous bold underlinings, erasures and overwritings reveals much about the vigour with which Beethoven pursued his goal of excluding the mother of his nephew Karl from guardianship and appointing him as guardian.

Draft memorandum to the Court of Appeal in Vienna, 18 February 1820

In the memorandum to the Court of Appeal in Vienna, Beethoven sets out all the circumstances surrounding the trial. Since the death of his brother Kaspar Karl on 15 November 1815, the gruelling disputes with his sister-in-law Johanna had continued, hampering his creative powers. After the Vienna magistrate had confirmed Johanna's guardianship in the autumn of 1819, appointed Leopold Nußböck as her co-guardian and rejected Beethoven's subsequent petitions, he hoped to finally settle the disputes in the appeal proceedings. However, it was probably forwarded in a revised version to the responsible appeal councillor, who ultimately successfully argued in Beethoven's favour. The following decision was made on 8 April 1820: The magistrate had to revoke his previous decisions, the previous guardians were excluded and Beethoven was appointed joint guardian with Karl Peters. Johanna did not give up, however, but appealed to the highest court, where she failed, however, as the Emperor rejected her complaint against the appeal order in a so-called court appeal. Thus, after almost five years of tension, the trial had finally found the solution Beethoven had been striving for.

The collection

Documents partly in Beethoven's hand

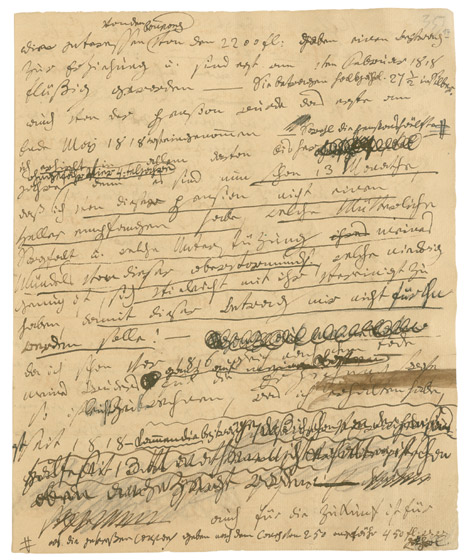

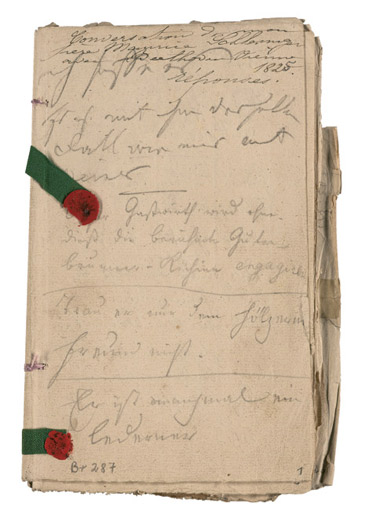

In addition to publishing contracts and the important 'annuity contract' with the patrons Archduke Rudolph and Princes Lobkowitz and Kinsky, the 'Documents partly in Beethoven's hand' section also contains individual notepads and records of conversations. At the auction of the Wilhelm Heyer Collection in Cologne in December 1926, Bodmer was also able to add a complete conversation booklet to his collection. From 1818 onwards, Beethoven was forced by his advanced deafness to conduct his conversations in writing. He used notebooks for this purpose, in which his dialogue partners wrote their questions and answers to the composer, who was hard of hearing. However, he then usually answered verbally. However, he also used the notebooks for notes and to record musical ideas. Today, the conversation notebooks are the most important biographical treasure trove alongside the letters.

Conversation booklet from 9 September 1825

This booklet was used on 9 September 1825 after a private premiere of the new String Quartet in A minor op. 132, organised at relatively short notice at the Viennese inn 'Zum wilden Mann', where a dinner was served. The interlocutors were Beethoven, his nephew Karl, the Parisian music publisher Maurice Schlesinger (he wanted to get a direct impression of the new string quartet, which he had purchased for his father's Berlin publishing house), the violinists Ignaz Schuppanzigh and Karl Holz, Sebastian Rau and an unidentified scribe, who is thought to be the innkeeper Sebastian Schmidt.

The collection

Music autographs

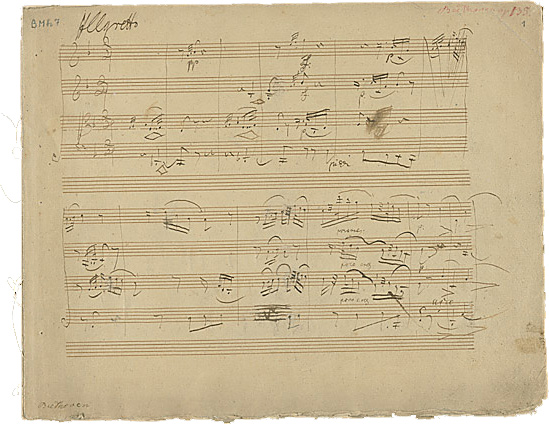

Bodmer was able to bring together a whole series of outstanding 'autograph manuscripts of Beethoven's works' in his collection. The collection contains, among other things, the so-called 'autographs' of several piano sonatas. Particularly noteworthy is the complete manuscript of the 'Waldstein Sonata' op. 53, which was the first music manuscript to be facsimiled during Bodmer's lifetime in an extremely elaborate process. However, the collection also contains manuscripts of songs, sonatas for piano and solo instrument and even several sheets for the 9th Symphony.

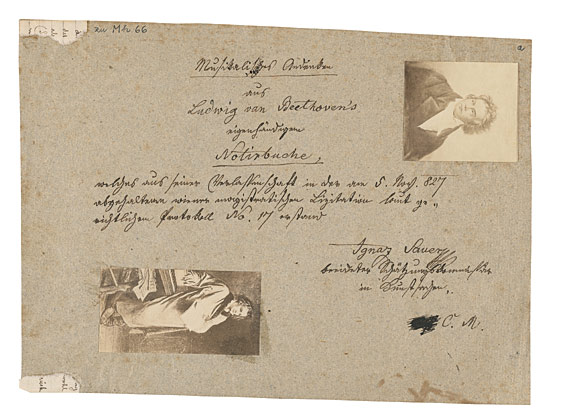

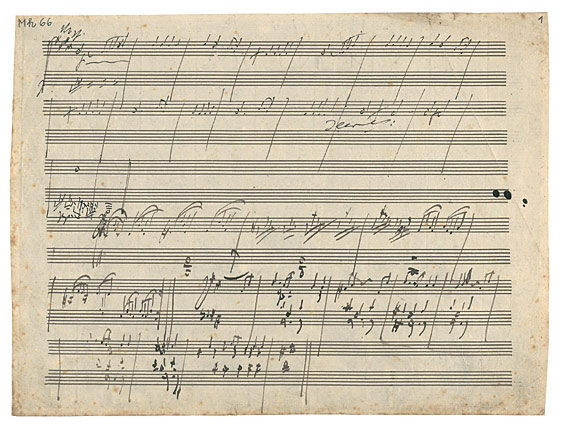

Beethoven's manuscripts for his last major composition, the String Quartet op. 135 in F major, will be presented here. For the collector Bodmer, this was a particularly fortunate case, as he was able to purchase the score of the first movement from the Wittgenstein Collection shortly after acquiring the complete set of parts in 1948. The autograph score was already kept in separate individual movements during Beethoven's lifetime, passed to various owners after his death and is now widely dispersed: the fourth movement is in the Berlin State Library, the 'Assai Lento' is in a museum in Morlanwetz (Belgium) and the whereabouts of the second movement are unknown.

String Quartet in F major op. 135, score of the first movement

The instrumental parts for the players - the part sets 'extracted' from the score - were usually made by professional copyists. In this respect, this set of parts by Beethoven's own hand is a rarity. In Gneixendorf, where Beethoven was staying on his brother Johann's estate in the autumn of 1826, there was a lack of a suitable scribe, but the publisher Schlesinger urgently needed the part copies as engraver's copies (instrumental music was usually published in parts for the performers at that time and only in exceptional cases as a score). Beethoven was therefore forced to be his own copyist.

Set of parts, first page of violin 1

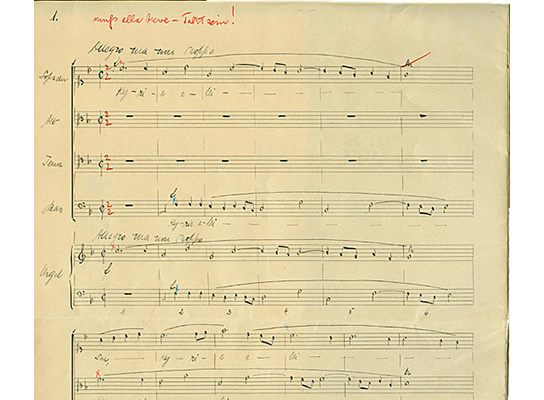

Beethoven prefaced the last movement with an unusual motto: 'The difficult decision', which is expressed musically by the conflict between two opposing motifs, which are also introduced from the outset: 'Grave: Must it be?' 'Allegro: It must be! It must be!'

Viola part, beginning of the last movement

There are several attempts to explain the quotation; Beethoven's friend and second violinist of the Schuppanzigh Quartet Karl Holz reports the following anecdote, which is supported by entries in conversation books: 'Beethoven had just completed the Quartet in B flat [op. 130] and gave the manuscript to his friend Schuppanzigh to perform, which he hoped would bring him a lot of money. Beethoven was all the more annoyed when he learnt after the production that a wealthy music lover known in Vienna, D[embscher], did not attend, claiming that he could subsequently have this quartet performed in his own circle and by capable artists; it would not be difficult for him to obtain the manuscript from B. He then turned to Schuppanzigh. This gentleman soon approached Beethoven through the intercession of a friend and asked him for the parts for the latest quartet. Beethoven then told him in writing that he would send the parts if Schuppanzigh was paid 50 fl. for the first performance. Quite unpleasantly surprised, D. said to the bearer of the ticket: 'If it must be -!' This reply was brought to Beethoven, at which he laughed heartily and immediately wrote down the canon:

'It must be! It must be!' [WoO 196]. The finale of his last quartet in F major, which he entitled 'Der schwer gefaßte Entschluss' [The Difficult Decision], was composed from this canon in the late autumn of 1826.'

The collection

Music copies and extracts

Throughout his life, Beethoven repeatedly made copies of works by other composers and produced excerpts. As a rule, he used them for study purposes. He made copies of works and solutions to problems that were of particular interest to him. In preparation for 'Leonore', for example, he worked extensively on Mozart's opera settings and excerpted from 'Don Giovanni'. In the last 10 years of his life, he developed a pronounced interest in fugue and canon technique, which then manifested itself in his compositions. He made several copies of Bach fugues for this purpose.

However, the copies of fugues from Johann Joseph Fux's 'Gradus ad Parnassum', the standard work on compositional theory, presented here are on a different level. They did not serve him (any more - he had also learnt from Haydn) for his own studies, but as a teaching aid for his pupil Archduke Rudolph. In addition to piano lessons, he also gave him composition lessons, for which he prepared teaching material himself. This bundle, kept in the archives of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, contains excerpts from various current writings on the teaching of composition as well as a detailed 'Introduction to Fux's teaching of counterpoint', including the two fugues that Beethoven then wrote down again. In this manuscript, which Bodmer acquired from the Roman antiquarian Karl Eugen Schmidt in 1931, Beethoven transcribed both fugues in clefs for string quartet. We can only speculate as to why: perhaps he wanted to give them to his pupil, or perhaps the theory lessons were to be supplemented by a practical lesson (string quartet). Incidentally, Schmidt doubted the authenticity of the manuscript because of its neatness. In any case, the collector Bodmer must have been delighted that he was able to acquire a further nine manuscripts a short time later, which Beethoven produced in connection with his teaching activities.

Excerpt from the 'Gradus ad Parnassum' by Johann Joseph Fux

The collection

Sketches

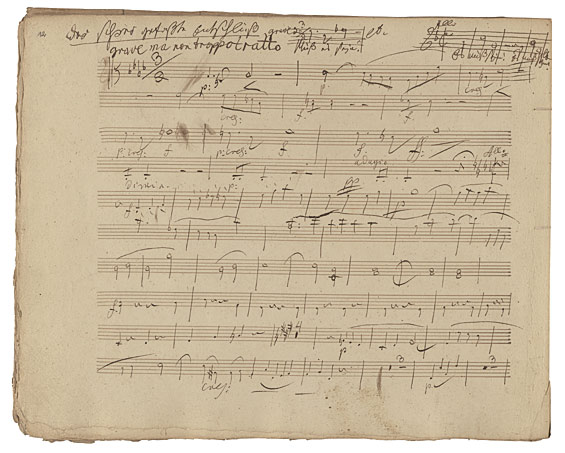

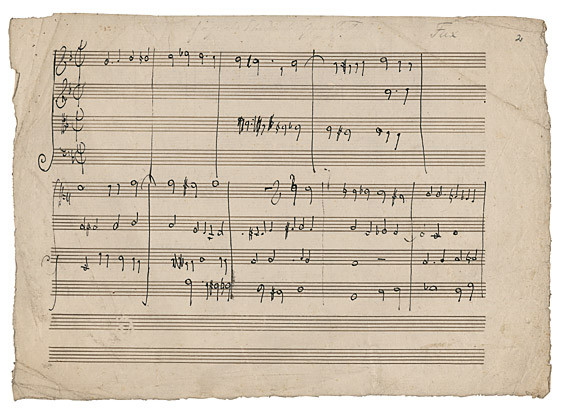

In addition to three large sketchbooks from the years 1811/1812 (sketchbook 'Petter'), 1819/1820 (sketchbook 'Wittgenstein') and 1823 (sketchbook 'Engelmann') with sketches for such important works as the 7th and 8th Symphonies, the Diabelli Variations, the Missa solemnis and the 9th Symphony, the Bodmer Collection also contains a large number of individual sketch sheets.

The sketch leaf for the Piano Sonata in C sharp minor op. 27 no. 2 ('Moonlight Sonata') was also originally part of a large sketchbook. Today it is known as the 'Sauer' sketchbook after its first third-party owner, the Viennese art and music dealer and appraiser of Beethoven's musical estate Ignaz Sauer. Originally it contained at least 48, perhaps even 96 leaves, but today only 23 are known to exist. Sauer acquired the book at the auction of Beethoven's musical estate and divided it into many individual leaves, which he gave away as souvenirs or sold for the - comparatively low - price of 20 to 30 kreuzer. For this reason, its original form can hardly be reconstructed today. Sauer provided the individual pieces with an endpaper on which the provenance and price were noted: 'Musical souvenirs from Ludwig van Beethoven's autograph notebook, which Ignaz Sauer, sworn appraisal commissioner in art matters, acquired from his estate in the Vienna magistrate's liscitation held on 5 Nov. 827 according to court protocol no. 17. [cancelled: 20 x] C.M. [= 20 Kreuzer Convention coin]'. The affixed photos are from a later date.

Endpaper for the sketch sheet

Bodmer acquired the sketch leaf in the 1930s. Today, only five sketch sheets of the 'Moonlight Sonata' are still available, all of which concern the third movement. The one from the Bodmer Collection was written first. On the page shown here, it contains an early, much simpler sketch of the second theme - which Beethoven refers to here as the middle idea - as well as two independent sketches in B minor. A further leaf is in unknown private ownership, three leaves are kept in the Biblioteca Estense in Modena, in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge and in the Musashino Ongaku Daigaku in Tokyo. A facsimile of the manuscript of the sonata, also kept at the Beethoven-Haus, was published by the Beethoven-Haus in 2003 and contains all five sketch leaves together with transcriptions.

Sketch leaf for the Piano Sonata in C sharp minor op. 27 No. 2

The collection

Revised copies

The Bodmer Collection contains various copyist's proofs of his works, checked by Beethoven and annotated in his own hand, most of which served as engraver's models for the respective publishers. These so-called 'revised copies' have an extraordinarily high source value, as they basically reproduce the 'last hand version' and often go far beyond the status of the autographs.

The following is a selection of nine pieces from the collection, in which copies of Beethoven's only opera 'Fidelio' are united. Beethoven revised his opera twice. The original version, which premiered at the Theater an der Wien on 20 November 1805, was cancelled after only two repetitions. In the first revision, Beethoven made drastic changes and reorganised the three acts into two. After two performances, this reworking was put on ice for many years. It was not until 1814 that the opera was in demand again and Beethoven produced a new reworking or partial new version.

The libretto was also virtually rewritten by the experienced theatre man Georg Friedrich Treitschke. Beethoven wrote to him at the beginning of March 1814: 'The score of the opera is written as terribly as I have ever seen one, I must look through it note by note (it is probably stolen), in short, I assure you dear T., the opera will earn me the martyr's crownn'. The final version was then premiered on 23 May 1814 with great success. During the revision phases, Beethoven had the arias and ensembles of the opera copied out by copyists after he had written them down once himself, then revised them, had them copied out again, revised them again and so on.

In this way, he created two different versions of some numbers and three or even four different versions of most of them. Beethoven only ever rewrote those sections himself that he had completely changed or composed anew. Thus the final stage of the composition is also documented here predominantly by revised copies. The copy of the trio Rocco/Leonore/Marzelline 'Gut, Söhnchen, gut' shows three layers of the composition side by side. In the first complete revision, Beethoven had deleted a passage of four bars in the middle, in addition to numerous small changes, which was therefore no longer included in the 1806 copy shown here. In 1814, Beethoven decided that he should include these four bars again and shorten the preceding section instead. He therefore removed a double leaf from an older copy of the unabridged version, cut off the superfluous bars and inserted the manuscript with the 1805 première version into the 1806 copy. This revised copy now shows the last version from 1814.

Copyist's copy with Beethoven's revision of the trio 'Gut, Söhnchen, gut' from the opera 'Fidelio'

The collection

Miscellaneous

Under the heading 'Miscellaneous', which did not yet appear in Max Unger's printed catalogue, Bodmer included relics such as locks of Beethoven's hair and everyday objects in the broadest sense such as a compass, money box, but also a desk and travelling writing desk in his handwritten supplementary catalogues. The section also contains printed material with handwritten additions, such as a New Year's greeting and journals in which Beethoven made marginal notes.

The impressive desk came from Beethoven's estate into the possession of his friend Stephan von Breuning's family, where it remained for over a hundred years. In 1929, it was sold to Stefan Zweig together with other memorabilia and finally acquired by Bodmer from his estate in 1953. It is safe to assume that the piece of furniture was in Beethoven's last flat in the 'Schwarzspanierhaus'. This is because Stephan von Breuning's son Gerhard explicitly mentions in his memoirs of his youth, published in 1874, that there were no pieces of furniture in Beethoven's so-called 'music room', in which otherwise only the most diverse prints, manuscripts and sketches lay around in wild disorder, 'except for the writing desk that was out of use at the time (which is now in my possession)'.

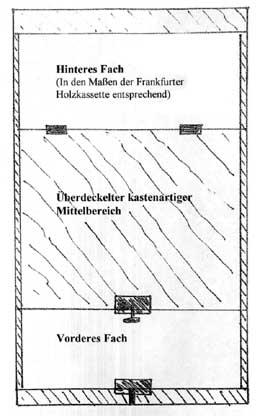

In the 19th century, it was repeatedly surmised that Beethoven's bank shares, his famous letter to the 'Immortal Beloved' and two portrait miniatures of unknown ladies - also taken from the Zweig collection by Bodmer - were in a secret compartment of this desk. Stefan Zweig was probably also convinced of this. However, there are also contradictory reports regarding the circumstances of the discovery. Sebastian Rau, for example, speaks of an 'old, half-mouldered box' in which the shares had been lying. Furthermore, no secret compartment could be found in the desk. Now, in connection with the special exhibition organised at the Beethoven-Haus to mark the 175th anniversary of his death, some objects from the possessions of Frankfurt music collector Nikolaus Manskopf, which had previously received little attention, have been examined more closely. Among them was a simple softwood box with a recessed sliding lid which, according to Manskopf, is said to have housed Beethoven's bank shares. This box can be fitted exactly into the back of one of the drawers on the left-hand side of the desk and could therefore actually have functioned as a kind of 'secret compartment'.

Schematic drawing of the top left drawer

The collection

Beethoven pictures

Bodmer also owned various pictorial representations of Beethoven. These include the miniature painting on ivory by Christian Horneman, which shows Beethoven as a young man in 1802, as well as full-length depictions of the composer walking by Joseph Weidner and Johann Peter Lyser. An aquatint by Franz Hegi shows 'Beethoven composes the Pastoral'.

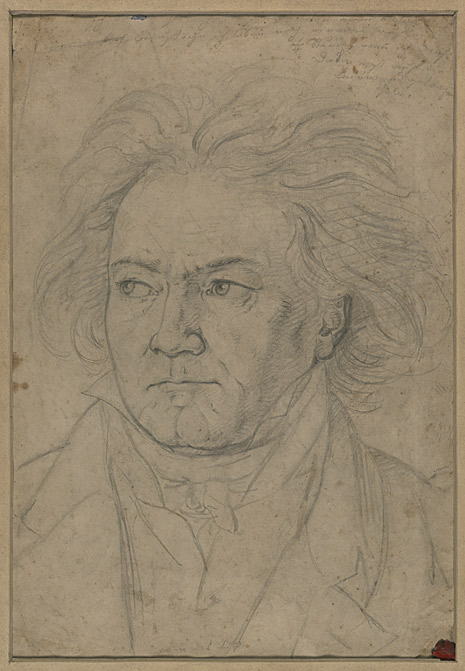

On display here are the portrait studies by August von Kloeber, which the Beethoven-Haus was later able to supplement with a chalk drawing. The painter, who was just 25 at the time, visited Beethoven in 1818 during his summer holiday in Mödling. His brother-in-law Baron von Skrbenski had asked him to paint a portrait of Beethoven for his gallery. Kloeber was warmly received and Beethoven actually modelled for him several times. Various studies were made during these sessions, of which a sketch of Beethoven's shoulders, arms and hands and a larger drawing showing the composer's head and shoulders have found their way into the Bodmer Collection.

Study for a portrait of Beethoven by August von Kloeber, 1818

The pencil sketch bears several handwritten entries by Kloeber for the conversation with the composer, who was already very hard of hearing at the time. These show that the painter had already begun work on his oil painting in Mödling, as he mentions that he first wanted to transfer parts of his study to the canvas before he visited Beethoven again.

Study for a portrait of Beethoven by August von Kloeber, 1818

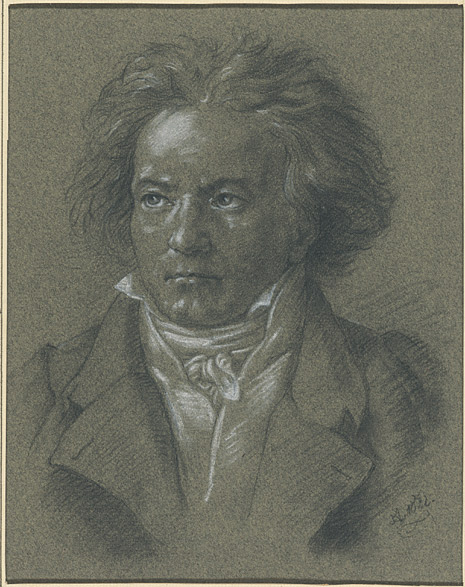

The painting that August von Kloeber created after these preliminary studies showed Beethoven and his nephew in full figure in a park landscape. Unfortunately, however, every trace of it has been lost. In 1822, Kloeber executed another portrait from memory as a chalk drawing, which the Beethoven-Haus was able to acquire in 1984. Although this portrait appears less lively and spontaneous than the pencil sketch of 1818, the artist succeeded in idealising the composer's facial features without hardening them in a classicist manner or distancing himself too far from the natural model.

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven in chalk by August von Kloeber, 1822

The collection

First and early prints

The Bodmer Collection also includes an extensive collection of printed music. The collector strove for completeness, especially in the first editions of Beethoven's works with opus numbers. After all, of the 138 works with opus numbers, he owned at least one copy of the first edition or a title edition of 116 works; he therefore lacked the corresponding printed music of 22 works. However, he must have been particularly pleased with the rare original editions with the composer's own handwritten entries, of which he owned six.

This includes Beethoven's manuscript copy of the piano part of the Trios for piano, violin and cello op. 1. This original edition has numerous fingerings in pencil in Beethoven's hand and contains a correction of the musical text on page 52. As the autograph is lost, this edition is the most important source for the three piano trios. They were composed in the first years in Vienna in 1794 and 1795, when Beethoven was still primarily composing for himself as a pianist; a dual role which his hearing impairment later prevented him from fulfilling. As was so often the case, Beethoven first presented his new works in small private performances for his patrons, this one at a soirée at Prince Lichnowsky's house.

Beethoven's hand copy of the original edition of the Three Trios op. 1

Beethoven broke new ground not only in the musical composition but also in the publication of his works. By contract (the contract is also part of the Bodmer Collection), the leading Viennese music publisher Artaria & Comp. undertook to supply Beethoven with 400 printed copies for 400 guilders, the printing costing 212 guilders. For two months, Beethoven had the sole right to sell the prints in Vienna at the proud price of 1 ducat (4.5 guilders) per copy. At the end of this period, Artaria was then authorised to sell the trios for his own account and at his own risk. Beethoven placed the following call for subscriptions in the 'Wiener Zeitung' in good time:

'Prenumeration on Ludwig van Beethoven's 3 large trio for piano forte, violin and bass, which will be published engraved by Artaria within 6 weeks and will be available from the author against return of the ticket after prior notification. The price of a complete copy is 1 ducat. The names of the prenumbers are printed in advance, and they enjoy the advantage that this work will not be made available to others until two months after delivery, perhaps only for a higher price. In Vienna you can prenumber with the author in the Ogylfische Haus in Kreuzgasse behind the Minorite Church No. 35 on the first floor.'

The printed list of subscribers enclosed with all copies of the first edition comprises 123 names. These include many members of the Viennese, Bohemian and Hungarian aristocracy. Beethoven underlined and marked numerous names with a + in his personal copy.

The collection

The Beethoven-library

The extensive collection of first editions, literature on Beethoven and documents on Beethoven's early reception form the core of Bodmer's Beethoven library. Antiquarian booksellers and art dealers from all over the world supplied the Swiss composer with offers. Nevertheless, the structure of the library can no longer be fully traced. Only a few letters and lists in his estate reveal when, how, why and from whom he acquired which books and sheet music.

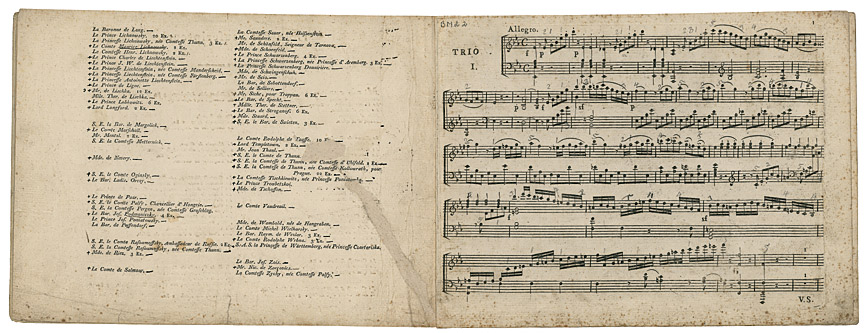

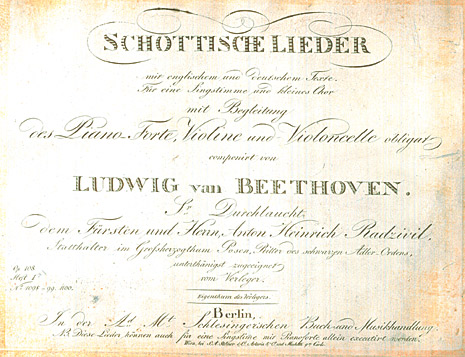

Bodmer's first port of call must have been the C. Lang book and art antiquarian bookshop in Zurich. The first German part edition of the 'Scottish Songs' op. 108 by Schlesinger, offered in 1918, marked the beginning of Bodmer's active collecting of Beethoven's first editions (the original editions of the violin sonatas op. 12 and the piano sonatas op. 31 come from older family possessions).

German first edition of the 'Scottish Songs' op. 108

In the early 1930s, Bodmer acquired several Beethoveniana rarities from the Rome-based antiquarian, writer and art collector Karl Eugen Schmidt.

He developed a close personal relationship with the Zurich antiquarian bookseller August Laube. He acquired three further first editions from him in 1955, whereby the original edition of the Piano Fantasy op. 77 was particularly important to him, as the autograph was already in his possession. The fourth item in his purchase decision, the facsimile edition of the 'Moonlight Sonata' published in Vienna in 1921, not only enriched Bodmer's small facsimile collection of six editions to date, but may also have been welcome to him because of the autographs of Arturo Toscanini, Moriz Rosenthal, Eugen d'Albert, Felix Weingartner, Frederic Lamond, Conrad Ansorge, Erich Kleiber and Bronislaw Huberman.

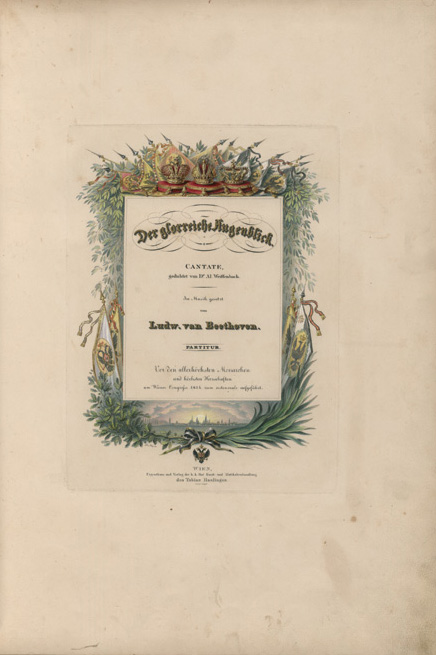

Bodmer did not compile a complete catalogue of his library during his lifetime; the catalogue published by Max Unger in 1939 contains the printed music, but does not mention the book collection. Bodmer compiled an initial catalogue entitled 'Bibliotheka Beethoveniana' in 1926 as part of the planned publication for the 100th anniversary of Beethoven's death. It contains a selection of 28 books that Bodmer considers 'apart from the relevant works in German, English and French' to be worth mentioning, whereby he has once again specially labelled the two rare first editions of the Beethoven biographies by Johann Aloys Schlosser and Franz Gerhard Wegeler with Ferdinand Ries. The following list of first editions contains the magnificent edition of Beethoven's cantata for the Congress of Vienna 'Der glorreiche Augenblick' op. 136 as a special rarity.

Binding of the magnificent edition of the cantata 'Der glorreiche Augenblick' op. 136, published by Haslinger in 1837

Title page of the magnificent edition

Bodmer strove for completeness in the first editions. He gained an overview of the gaps in his holdings and compiled lists of desiderata. He also drew up a more detailed catalogue of his first edition library in booklet form, which showed him both the inventory and the gaps in his holdings, and which he used until his death. He reserved half a page of the DIN A5-sized booklet for each work with an opus number. Under the opus number, he gradually listed the respective editions (not just first editions) from his collection, first in pencil and later in biros. Before the opus number, he marked the collection status in his own way with the following designations: diagonal red-blue double line '= first edition complete', diagonal blue line '= first edition partially complete', pencil circle '= still missing in collection', red 'O M = original manuscript in collection'. However, the inventory catalogue provides no information about dealers or even purchase prices, and Bodmer only mentions previous owners and collections in isolated instances.

Inventory catalogue of first editions with opus numbers

In the library of the Beethoven-Haus, the books and sheet music are now shelved together, each shelfmark beginning with 'HCB'. Analysing the electronic inventory data gives the following picture for Bodmer's library:

1) Literature in total: 886 titles, focus: literature from the 19th century (from 1797), but the most important secondary literature up to 1955 is also represented; of which:

• 177 books, mainly on music history, some Viennensia

• 360 books about Beethoven, including the early memoirs and biographies

• 150 journals reporting on Beethoven, including many from the 2nd half of the 19th century.

• 190 Beethoven-essays in individual journal issues

• 9 antiquarian catalogues

2) Total sheet music: 694 issues, of which:

• 334 individual editions of Beethoven-works (119 original editions, 6 original editions with autograph entries by Beethoven, 35 first editions, 64 title editions, 110 early editions)

• 47 pocket scores (Eulenburg, Lea) of works by Beethoven

• 7 Beethoven facsimiles

• 241 editions by other composers (mostly early editions)

List of the most important literature on Hans Conrad Bodmer

Auf den Spuren Beethovens. Hans Conrad Bodmer und seine Sammlung, von Nicole Kämpken und Michael Ladenburger, Bonn

2006.

Martin Bircher, Martin Bodmer - sein Leben, seine Bücher, in: Martin Bircher, Elisabeth Macheret-van Daele und

Hans-Albrecht Koch, Spiegel der Welt: Handschriften und Bücher aus drei Jahrtausenden, hrsg. von Ulrich Ott und

Friedrich Pfäfflin, Cologny und Marbach 2000, S. 15f.

Daniel Bodmer, H.C. Bodmer, in: Zürcher Taschenbuch auf das Jahr 1958. Herausgegeben mit Unterstützung der

Antiquarischen Gesellschaft von einer Gesellschaft zürcherischer Geschichtsfreunde, 78. Jg., Zürich 1957, S.

1-9.

Martin Bodmer, Über den Begriff des Sammelns in: Musik und Dichtung. Handschriften aus den Sammlungen Stefan Zweig

und Martin Bodmer, Cologny-Genève; eine Ausstellung der Fondation Martin Bodmer in Verbindung mit dem Museum

Carolino-Augusteo Salzburg, Cologny 2002, S. 247-261.

Sieghard Brandenburg, Die Sammlungen des Beethoven-Hauses in Bonn, in: 1889-1989 Verein Beethoven-Haus, Bonn 1989,

S. 117-136.

Sieghard Brandenburg, Beethovens Briefe. Editionen aus zwei Jahrhunderten. Ausstellungskatalog Beethoven-Haus, Bonn

1996.

Samuel Geiser, Beethoven und die Schweiz, Zürich und Stuttgart 1976, S. 214-224.

Hermann Hesse, An einen Musiker, Olten 1960.

Theodor Heuss, Tagebuchbriefe 1955/1963, hrsg. und eingeleitet von Eberhard Pikart, Tübingen und Stuttgart 1970.

Internationale Musik-Ausstellung Luzern, 16. Juli-1. September 1938 im Rathaus am Kornmarkt, [Katalog], hrsg. von

Franz Brenn, Luzern o.J. [1938].

Kritischer Epilog zu den Junifestwochen, in: "Die Zürcher Woche" vom 18. Juli 1952.

Michael Ladenburger, Max Unger als Musikwissenschaftler, in: Zwischen Musik und Malerei. Der Beethoven-Forscher Max

Unger und seine Freundschaft mit Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, hrsg. von Michael Ladenburger, Bonn 2000 (=

Veröffentlichungen des Beethoven-Hauses, Ausstellungskataloge Bd. 8).

Oliver Matuschek, Ich kenne den Zauber der Schrift. Katalog und Geschichte der Autographensammlung Stefan Zweig,

Wien 2005.

Felicitas von Reznicek, Gegen den Strom. Leben und Werk von E.N. von Reznicek. Mit einer Darstellung der

Kompositionen von Leopold Nowak, Zürich-Leipzig-Wien 1960.

Romain Rolland - Stefan Zweig. Briefwechsel 1910-1940, hrsg. von Waltraud Schwarze, 2. Bd., Berlin 1987.

Joseph Schmidt-Görg, In memoriam Dr. med. Dr. phil. h.c. H.C. Bodmer in: Beethoven-Jahrbuch 2. Jg. (1955/56), Bonn

1956, S. 6-10.

Sonderausstellung aus der Beethoven-Sammlung H.C. Bodmer - Zürich = Exposition spéciale de la Collection Beethoven

du docteur H.C. Bodmer - Zurich / Beethoven-Haus Bonn. H.C. Bodmer, Bonn 1953.

Max Unger, Eine Schweizer Beethoven-Sammlung, in: Neues Beethoven-Jahrbuch 5. Jg 1933, Augsburg 1934, S. 28-47.

Max Unger, Die Beethoven-Handschriften der Familie W. in Wien, in: Neues Beethoven-Jahrbuch, hrsg. von Adolf

Sandberger, 7. Jg., Braunschweig 1937.

Max Unger, Eine Schweizer Beethoven-Sammlung. Katalog, Zürich [1939].

Max Unger, H.C. Bodmer, in: Musica 10. Jg. (1956), S. 540.

Dagmar Weise, Ungedruckte oder nur teilweise veröffentlichte Briefe Beethovens aus der Sammlung H.C. Bodmer, in:

Beethoven-Jahrbuch 1. Jg (1953/54), Bonn 1954, S. 9-62.

Dagmar Weise, Gedenkstunde für H.C. Bodmer im Beethoven-Haus Bonn, in: Schweizer Monatshefte 36. Jg. (1956/57), S.

905-907.

Dagmar Weise, Schweizer Vermächtnis für das Beethoven-Haus, in: Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 121. Jg. (1960), S.

410-412.

Dagmar Weise, Vermächtnis für das Beethoven-Haus in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 30. April 1960.

Zürcher Familien, in: Die Zürcher Woche, 27. März 1953.

Zweigs Welt der Autographen, hrsg. von Nicolas Baerlocher und Martin Bircher, Zürich 1996.

Imprint

Publisher:

Beethoven-Haus Bonn

Bonngasse 24-26

D-53111 Bonn

Germany

Content of the internet exhibition:

Dr Nicole Kämpken

Dr Michael Ladenburger

The special exhibition was shown in the Beethoven-Haus from 29 May 2006 to 3 September 2006.