The Life and Work of De Meo

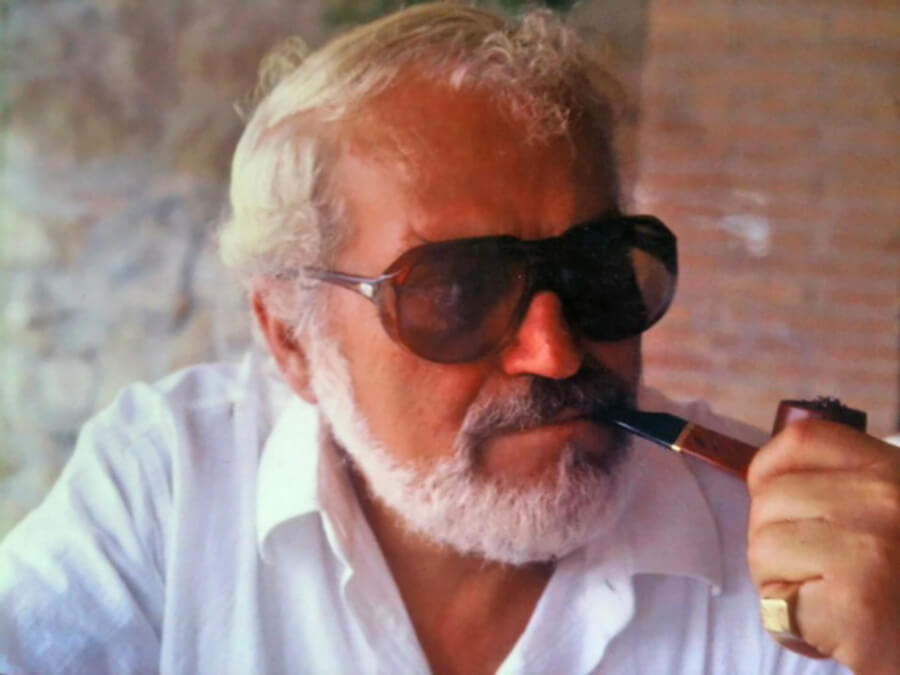

Tommaso De Meo was born on July 17 th, 1924 in Andria (Bari). As a pupil of Roman artists such as Stradone, Tani and Ciavatta, he studied painting at the "Accademia Romana di Valle Giulia". Alas, his education was cut short when he was drafted into the navy. In 1943, the then 19 years old Tommaso fell into enemy hands quite by chance when a nearby Carabinieri barracks was ambushed by Nazi troops. Many of the Romans captured on that day were forced into hard labour in Austria, and De Meo was deported to Graz. There, a fellow inmate's violin playing not only made him discover Beethoven's music, but gave him solace while trying to survive the atrocious conditions in the labour camp. In those days, De Meo was able to reconnect with his artistic side: he painted portraits of several of the camp's officers, gaining him their good will. During that winter, however, he would lose two of the fingers on his right hand to frostbite.

During the 1950s, De Meo embarked on his career as an artist while working at the postmaster general's department. During that time, a grave accident cost him one eye and almost totally blinded the other; for several years De Meo lived in nearly total darkness, until a number of surgeries were able to give him back at least partial eyesight. This impairment, which very well might have spelt the end of his artistic pursuits, led to a deep human and artistic connection to the similarly afflicted Beethoven. In the composer, De Meo saw a teacher, one who could give him strength and hope through his music. Thus began a period of intense studies regarding the life and works of Beethoven, with De Meo's admiration for the composer becoming a creative engine for his own artistry. During several travels to Bonn and Vienna, he began work on several studies for his later "musical" paintings. Between the years 1964 and 1966, he painted the series based on Beethoven's symphonies, capturing his interpretation of the music on canvas, movement by movement.

Other oil paintings dealt with Fidelio, the Coriolan Overture, Egmont or the Missa Solemnis. In the course of five years, he painted over 60 works about Beethoven: during the festivities for Beethoven's 200th birthday, the symphony cycle was exhibited at the Palazzetto Medici in Rome, with De Meo being honoured by the cultural department of the German embassy. However, music was far from the Roman artist's sole subject matter. In many of his numerous works, De Meo sent a warning to mankind: for even though man had the capacity to create sublime works of art and bring forth geniuses such as Michelangelo or indeed Beethoven, he also had the potential to destroy his own kind.

De Meo spent his final 20 years in relative solitude in the Roman countryside, surrounded by his Beethoven-paintings, from which he was inseparable, since they symbolised both his own life story and his life-long reverence of Beethoven. On December 17th 2010, the 240th anniversary of Beethoven's baptism, he passed away in Rome. His wish was for his beloved paintings to be bequeathed to the Beethoven-Haus after his death, a wish that his children happily saw fulfilled: during a ceremonial act held in the Chamber Music Hall, the paintings were presented to the Beethoven-Haus on December 17th, 2011.

Beethoven's Symphonies in Pictures

The First Symphony

On the following pages, each of the series' paintings will be given a brief description. Of great help in this interpretation was an audio tape which De Meo himself recorded a few years before his passing in order to better explain his life's work to posterity.

The energy of the universe is gathering, condensing into a fiery tornado which rages above a red and barren earth. De Meo paints a wasteland devoid of human presence, in which withered weeds are the only signs of life. This desolate landscape's intense red hues are in sharp contrast to the blue tones of the sky.

First Symphony, First Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1964.

First Symphony, Second Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1964.

This blue-tinged painting depicts a scene of creation: from the unruly waters arise rocks, whose ostensibly jagged lines, at closer inspection, appear to be more organic, even reminiscent of human faces. The waters, the earth and the heavens are separating into distinct entities; a world is born.

First Symphony, Third Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1964.

The choice of architectural themes in this picture is by itself an exception from the majority of paintings inspired by Beethoven's music, for most painters either use natural landscapes or fully abstract imagery. If one looks more closely at this picture, its most striking aspect would be the curved contours of the architecture, in which the movement of the music appears to manifest itself. The artist had called the First Symphony an expression of the almost inebriating surge of emotions precipitated by the power of the music. Thus, the flowing architecture may express the emotions stirred within the deeply moved listener.

First Symphony, Fourth Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1964.

The sky is astir with the beating wings of black carrion birds, the blood red desert replete with the bleached bones of dead animals - De Meo's imagery ends with a grim vision, a warning memento to mankind.

The Second Symphony

Second Symphony, First Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1964.

In the series addressing the Second Symphony, the artist deals with a tragic phase in the composer's life, namely the recognition of his advancing hearing loss. De Meo's motif of choice are poppy-coloured flowers swaying in a gentle breeze. These particular flowers appear to be irises, whose natural colours are blue, purple, or yellow and whose petals face downward: the iris as a symbol was subject to many interpretations in Christian culture and Oriental literature, from being associated with the Virgin Mary to representing a love scorned.

With this idyll, the artist expresses Beethoven's attachment to nature, which was most apparent in his long, solitary walks. The flowers in the centre of the otherwise gaunt landscape symbolise the growing solitude of the great musician.

Second Symphony, Second Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1964.

To Beethoven, his own life has become bleak and dreary. De Meo shows the musician's crisis via a sombre sky in which the gathering clouds signal the onset of a storm. The musician is unable to find any solace in the idylls of nature. The withering flowers are a metaphor for Beethoven's forlorn despair: the loss of his hearing is now a certainty, the downcast blossoms a testament to his despondency.

Second Symphony, Third Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1964.

De Meo views the third movement of the symphony as a triumph of art over adversity. The composer seems to have crossed the nadir of his despair, drawing new strength from his music. Gaily coloured, fanciful figures are twisting as if in a dance. De Meo shows music as a dream which consigns all pain to oblivion.

Second Symphony, Fourth Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1964.

With the fourth painting, De Meo addresses Beethoven's struggles against the recurring desperation over his loss of hearing. His inner demons resist the composer's attempts at finding peace in spite of his impaired senses. Before the musician, the abyss looms like a hellish door: despair and loneliness, here shown as a grotesque, fiery grimace, endeavour to possess the composer.

The Third Symphony

Third Symphony, First Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

Regarding this composition, De Meo wanted to focus on the symphony's references to Napoleon, since Beethoven had originally planned to dedicate the piece to him. Thus, De Meo tries here to express the musician's initial admiration for the great general. A wide, blood red path stretching to the horizon divides the painting into two halves: on the right, the towering columns, reminiscent of the architecture of ancient Rome, symbolise imperial power; in contrast, the left side shows red, unhewn blocks of stone, which evoke ruined cities, conflagrations and the havoc of war. This red is in stark contrast to the cool blue of the plains on the right. The differences in colour between the contrasting architectures emphasise the distinction between power and its consequences: the initial enthusiasm for Napoleon, whom Beethoven saw as an equal to the Roman consuls of old, suddenly turns to horror and chagrin among the fires of his wars of conquest.

Third Symphony, Second Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

The second movement of the Third Symphony - the aptly named Sinfonia Eroica - is also tied in to the overarching Napoleonic theme: the painter naturally sees the music in a larger, general human context. Hence, the great relevance that the funeral march has for De Meo, since his worldviews were shaped in large part by his own painful memories of the time spent in a labour camp during the Second World War. Incidentally, the significance given to that funeral march matches the views of several 20th Century artists, such as those of Arthur Paunzen, who, in the wake of the Great War, let his experiences in that conflict guide his visual interpretation of the Eroica's funeral march. De Meo's vision of the 1804 composition is a prophecy of the devastating consequences of Napoleon's Russian Campaign. Accordingly, both landscape and architecture of De Meo's artistic realisation are indicative of the Grande Armée's catastrophic defeat in Russia in 1812. The long march of the innumerable nameless vanquished dominates the painting's foreground, losing itself in the remote vastness of a frigid icescape. At the same time, a barren tree's shape, reminiscent of classic representations of the goddess of victory's pose, seems to mock the routed army. However, not all hope is lost, as the solitary bright star in the dark sky would imply.

Third Symphony, Third Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

From the upper corners of the picture, two arms reach into its centre, the steel bracelets around the wrists suggesting the manacles of a prisoner; and yet, the chains are missing. After the terreur of the Revolution - the horrors of the guillotine possibly represented by the headless figure dominating the painting - after the suffering of the Napoleonic Wars, after the oppression of foreign rule, a spirit of liberty seems to rise out of the bloody, fiery turmoil. The forlorn and insignificant triumphal arch, relegated to the background, shows how ephemeral and transient the glory of arms and the fervour of conquest truly are.

Third Symphony, Fourth Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

The smoke of war is clearing from the battlefields of Europe - the sky, blue once more, reveals the rebuilding of cities, of nations, of civilisation itself. Beside the dead, barren trees, green blades of grass are lushly sprouting from the ground; from the ladders and scaffolds of this new beginning, one can almost hear the sounds of the builders' and carpenters' tools.

The Fourth Symphony

Fourth Symphony, First Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

The series about the Fourth Symphony once again illustrates the link between the music as understood by the artist and its realisation on canvas. The carefree jauntiness of the Fourth Symphony, written in the summer and autumn of 1806, is a testament to the composer's joyful elation born of his love to Josephine Deym (née Brunsvik) - De Meo saw therein evidence of an inner poise and serenity hitherto unknown in Beethoven's life. Thus, it is that very serenity, expressed in cool yet intense shades of blue, which is at the core of the cycle about the Fourth Symphony. The first painting reflects the opening motif of the first movement: the distinctive, drawn out b-flat minor, so sombre and gloomy at first, subsequently gives way to brighter, less tense impressions. In De Meo's treatment, this first tone is transformed into an interminable expanse of water, its murky surface separated from the even darker night sky only by a faint shimmer of light on the distant horizon. And yet, where the dark night and deep, calm waters would speak of tranquillity, the painter seems to sense a certain underlying restlessness: the jagged shores of rock or ice at the bottom of the picture, as well as the shadowy flock of seagulls suggest some hidden, restless dynamics at work behind and underneath the calm surface.

Fourth Symphony, Second Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

Like the gnarled, jagged finger of a rocky titan, the earth itself appears to reach for that faraway, solitary celestial light, just to lose itself in the primordial nothingness. Both in its forceful pursuit of that light and in its inevitable dissolution, this motion echoes the crescendo of the symphony's second movement, which likewise closes with powerful energy transitioning into gentle serenity.

Fourth Symphony, Third Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

The once calm waters have been whipped into a frenzy by a massive storm. In the foreground, the spray of the waves condenses into clawed monstrosities threatening to drag Creation itself into the murky depths, while beyond the horizon, the very heavens and their harried clouds appear to flee from this scene.

Fourth Symphony, Fourth Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

For the first time, living nature makes an appearance, while in the sky, light and darkness are joined into a new, perpetually moving harmony. The earth itself appears renewed, as well: gentle hills have now replaced the jagged rocks of prehistory, and the first dabs of warm, vivid colours herald the dawning of a new age.

The Fifth Symphony

Fifth Symphony, 1. Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

Fate, the dominant topic of the Fifth Symphony, first appears before us in the guise of a darkened but still blazing sun, which - analogous to the composition's illustrious opening theme - rises mightily above the roofs and towers of a great city. Alas, its otherwise all-illuminating light is wasted on a city whose houses have neither doors nor windows - akin to fate herself, who may come unto men, yet is not received. The light is in the world, yet men love darkness rather than light.

Fifth Symphony, Second Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

The four notes of the opening motif are reflected, like light from distant cave mouths, in the tranquil waters of the second movement: their reflections are drawn through the gentle waves, are refracted in them, yet are always clearly visible. The forbidding, craggy landscape itself, with its vertical and horizontal brush-strokes, which are only ever pierced by that glow, speaks of both dissociation and harmony, leaving the beholder with an impression of a painted vibrato.

Fifth Symphony, Third Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

Per aspera - in the presence of the forces of fate and nature, the human mind comes undone. Open, naked, stripped of all defences, the mind, deprived of its terra firma, cannot withstand the onslaught any longer; intellect and reason are annihilated, their remains draining away through the chasms and crevices of a shattered earth. The only point in the dismal, storm-tossed sky in which the Roman painter grants the eye a modicum of light is ripped apart by a jagged thunderbolt as if by Jupiter Fulgur himself.

Fifth Symphony, Fourth Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

Ad astra. The rough and sublime journey is over: a blazing sun, that no shadow and no darkness can stand in front of, at last fills the universe with its light in a final, scintillating triumph. Where once stood a city which haughtily shut itself away from the light, there is now the earth, which may seem barren, yet whose soil bears life everywhere; life which grows and strives towards the pure light. Only one figure in the corner, whose shape is reminiscent of a man transformed into a tree by the gods, is pointed downwards, contrary to the motion of the rest of nature.

The Sixth Symphony

Sixth Symphony, 1. Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

In De Meo's work, one can find a rather novel approach to depicting Beethoven's Sixth Symphony, also known as the Pastoral Symphony, in which the composer deals with "memories of country life". The painter expresses Beethoven's bond with nature; to that end, he uses images whose topics are predictably derived from the movements' titles, made by the composer himself. However, there are also noticeable divergences in the Roman artist's interpretations.

The first painting opens the cycle in the manner of a stage production: like a rising curtain, the drooping branches of a weeping willow reveal an idyllic vision of nature. The picture is thus dominated by the lush green of the fertile fields, and framed by the gentle rolling hills on the horizon, as well as the colourful dots of flowers and wild grass in the foreground. One single tree juts proudly from the plain, its crown bathed in the light of the evening sun - within the harmony and chromatic placidity of this scene, which otherwise conforms rather thoroughly to Beethoven's description of the first movement as a wellspring of "cheerful feelings", the solitary tree in a nature devoid of humans is a reminder of the subject of isolation, so common in De Meo's work.

Sixth Symphony, Second Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

Called "the scene by the brook" by Beethoven, it is that very current which takes centre stage in the artistic transposition of the symphony's second movement. Here, the first differences between the composer's titles and the painter's interpretations become apparent: though indeed beginning on the right margin as a diminutive rivulet, its waters, upon cascading into the valley, turn into a mighty river, a lake, even - so vast that on its opposite bank, the lines between land and water seem to blur and become one. The idyllic tranquillity of the first painting gives way to a harsh and energetic depiction of nature, one in which bare, skeletal trees rise to meet the swiftly gathering clouds of a coming storm.

Sixth Symphony, Third Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

Both in its choice of subject matter and its abstract rendering, De Meo's painting of the third movement of the symphony differs from its predecessors within this cycle. Whereas Beethoven tried to represent the "happy gathering of country folk", De Meo's interpretation, with its images of colourful, but twisted and barren trees, seems like a bleak caricature of a joyous village dance. In the dance tune's stead, it may well be the swelling gusts of the gathering thunderstorm that drive the figures to and fro; instead of merry laughter, one might hear the mournful groaning of the trees in the wind. De Meo's picture fills the viewer with a sense of foreboding for that storm, which is the defining theme of the fourth movement.

Sixth Symphony, Fourth Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

The fourth painting of the Sixth Symphony now shows the once implied storm in its full, violent power. As is often the case with De Meo, it is the trees which are most subjected to the forces of nature: their leafless boughs twisted by the wind, their fragile trunks almost uprooted, they seem to be unable to defy the storm much longer. A most striking aspect is that it is the similarity between this and the calm of the first painting - the grass no longer gently waving, but whipped by the gale, the hills on the horizon bathed in a menacing, reddish glow by the thunderheads - which elucidates the difference between the two tableaux. The harmonious, sedate greens of the first painting are here set against vigorous brush-strokes and the sharp contrast of the complementary colours red and green, all the better to enact the oscillating energy of the thunderstorm.

Sixth Symphony, 5. Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

Earthy tones of brown prevail in the final painting of the Sixth Symphony. In the foreground, colourful flowers line the bottom margin. A hill with bald trees is at the centre of the picture. Beyond, the sun rises, whose brilliant light dominates all. Around it, a sprawl of colours - the rainbow hues of the luminescent sky are reflected in the many-coloured flowers at the bottom. The brightly coloured scene is representative of a reawakening of life, of a renewed repose and life-giving harmony after the devastating violence of the preceding storm. Nature, resplendent once more, reaches for the sun. Again, De Meo refrains from depicting humans, even though the sea of flowers bears some likeness to a joyful throng: nature and the renewal of all things are the principal topics.

The Seventh Symphony

Seventh Symphony, 1. Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

In the annotations to his paintings, De Meo, referring to Richard Wagner, defines Beethoven's Seventh Symphony as "the apotheosis of dance". In this purest and most exalted form of dance, the movements of the human body and the rhythm would virtually become one. He perceived the first movement of the symphony as mystical and contemplative, which is reflected in his choice of imagery: in a mysterious, mist-shrouded scene set in the orient, forbidding, rocky peaks rise into the sky behind a small pagoda. Said pagoda, while standing by itself in the deserted valley, seems nonetheless not abandoned, as the lights behind its windows would attest to. The decisive aspect of the overarching theme of dance is the wind, which - undeterred by the starkly solid mountains - would appear to play with the supple trees and the ephemeral wisps of the clouds and the fog.

Seventh Symphony, Second Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

Owing to the solemn nature of the second movement, De Meo views it as another funeral march, which he links to the second movement of the Third Symphony "Eroica". Accordingly, he depicts a grim landscape, which he calls "a blood-soaked marsh", representing death. A fiery, ominous sky watches over the red quagmire, from which scrawny, withered trees rise.

Seventh Symphony, Third Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

The Seventh Symphony's third painting is the first to show human figures explicitly. On the right margin, a male figure is helplessly raising his hand towards a sensual, long-haired female form, while she is dancing towards the black crag rising menacingly out of the red waters in the picture's centre. In its inherent energy, her powerful, yet graceful pose stands in stark contrast to the three wraithlike female figures wearily cowering on the rock like resting crows. Movement and contrast suggest that hers is indeed the dance of death: despite his best efforts, man cannot prevent his companions from being torn from this life by this last dance, whose portentous magnetism even draws and condenses the very elements around it.

Seventh Symphony, Fourth Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1965.

Above the limpid sea and the sublime masses of ice, a many-towered, yet desolate city of ice looms like a mirage in the morning light. Is it there that we may find our life's lost companions? Will all our journeys end in yonder city? It seems like De Meo is asking us those questions. Above us, a murder of crows flies eerily by, the birds' beating wings and plaintive cries accompanying us like music on our final journey.

The Eighth Symphony

Eighth Symphony, 1. Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1966.

The defining theme of the works dealing with the Eighth Symphony is the stage: all four paintings show some kind of mise-en-scène, in which the human condition is understood primarily within the context of a performance - including the rendering of the first movement, of which De Meo said, "see how the tiny firefly is able to charm the dancer". A vague female form in a wide skirt is standing at the centre of a reflecting sheet of water; she raises up her arms in an attempt to catch the minuscule firefly with her bare hands. The reeds growing out of the water all around her frame the scene like a stage setting, while giving off an air of menace, like the fangs in the mouth of a monster.

Eighth Symphony, Second Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1966.

The threat the audience poses to the creative artist, previously just implied, is now fully realised in the portrayal of the second movement: of the dancer, only the feet in the distinctive ballet shoes remain, forever frozen in a pointe, bathed in the blood red glow of the limelight. Meanwhile, the stands of the amphitheatre - whose ghastly, clawed dreadfulness may point to the historical consciousness of the Roman De Meo - are about to grab, seize, pillage whatever is left.

Eighth Symphony, Third Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1966.

In a reversal of Moses' parting of the Red Sea, a lone figure - its attire reminiscent of Beethoven's era - walks on a red, soaked path. In this case, it is the cloven land and its claw-like, bony trees that portend doom rather than salvation. The figure at the vanishing point of the painting is also at the centre of the four elements: framed by the stage of a natural spectacle, it is unclear whether the elements emanate from that form or are drawn towards it; whether man rules over nature, or nature commands him. De Meo perceives the third movement as an awakening from a dream. Man is no longer caught in his own musings and flees this imaginary place by shedding himself of the dreams' bonds.

Eighth Symphony, Fourth Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1966.

In the final picture of the eighth cycle, the image of the stage is blurred once more - if anything, it is implied in the shapes of the trees which frame the scene like wooden worshippers. Beneath the sky of a wrathful Jupiter, men pursue the most elementary of cultural endeavours, tilling the poor soil, subduing the earth: whether the trees' pose is a sign of adoration or lamentation is left uncertain, as is the question of whether it is directed at the old pagan gods or the new rulers.

The Ninth Symphony

Ninth Symphony, 1. Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1966.

In a landscape of grassy fields, a mother - one infant on her shoulder, an older son holding her hand - gazes expectantly at a setting sun, which bathes the ever darkening world in a last blazing red light. The onset of darkness may point to the crescendo in the first movement, whereas the feeling of anxious longing, ever growing within hopeful expectance, would fit well with the powerful, almost martial theme of the movement, underscoring the dramatic nature of the painting. About this work, De Meo himself said: "indeed it is we who appear to wait every day for something, which alas never arrives."

Ninth Symphony, Second Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1966.

In his artistic interpretation of the second movement, De Meo's subject of choice is the lost city of Atlantis. There is an almost palpable feeling that the city wants to leave the bottom of the ocean behind, to shine in new splendour under the light of the sun. In the painting, this tableau is represented in a rather abstract fashion: one single ray of sunlight is able to pierce the murky depths and reach the indistinct outline of the city. Above the surface, among the clouds ablaze with light, a massive shadowy figure appears to be about to take over the entire scene. There is a vivid energy to this picture, which quite matches the rhythm and the mood of the lively second movement.

Ninth Symphony, Third Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1966.

The leisurely, sedate tempo of the third movement's adagio is, as is to be expected of De Meo, rendered as a stark concrete jungle of tall skyscrapers which appear to storm heaven itself. The gentle, natural motions of the sea and the playful movements of the cloud have given way to the inexorable aspirations of mankind. De Meo thus expresses his pessimistic world-view, comparing this concrete city to coffins; 200 years after Beethoven's birth, mankind has lost its capacity to create true art and shall henceforth be reduced to building burial cases. The wistful melancholy of the third movement, to the artist, seems to caution mankind to reflect upon its past.

Ninth Symphony, Fourth Movement

Oil-based paint on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Rom, 1966.

This last painting of the "Symphony Cycle" shows the finale of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony in an uncommon light. While other painters often choose to depict human beings, thereby alluding to the human voices of the final chorus, De Meo paints a single flag, fluttering in the wind among the mountains.

The joy of which the chorus sings is expressed through the many vivid colours of the image, while the vivaciousness of the music finds its parallels in the flag's vigorous fluttering and the lively brush-strokes that make up the illustration.

Although generally positive in its imagery, De Meo cannot help but see a stark contrast between the hopeful visions offered by Beethoven's music and the reality of the mid-20th Century. Hence, his image isn't a mere happy idyll; instead, its fierce wind, its harried clouds and the sky's gloomy hues are meant to startle and arouse the beholder, as well.

In closing, we once more yield the floor to the painter himself, who commented on the final painting of the cycle with the following words:

"Indeed it is joy which the chorus expresses when exclaiming, 'onward, brothers, let us unite, for in those lofty heights among the stars, the true human being shall wait for us'

"But you, do you not think that the path on which we have set out shall not lead us upwards, but ever further down? Are we not destroying our world? Shouldn't we find joy in loving each other? ...Alas, we are nowhere near restoring our world to its native bliss - can't you see?

I for my part have now reached the end - now it is upon you to judge and decide."

Legal notice

Publisher:

Beethoven-Haus Bonn

Bonngasse 24-26

D-53111 Bonn

Germany

Texts:

Sabina Libertini M.A.

This temporary exhibition was shown from 17.12.2011 to 31.3.2012 in the H. J. Abs Chamber Music Hall of the Beethoven-Haus.